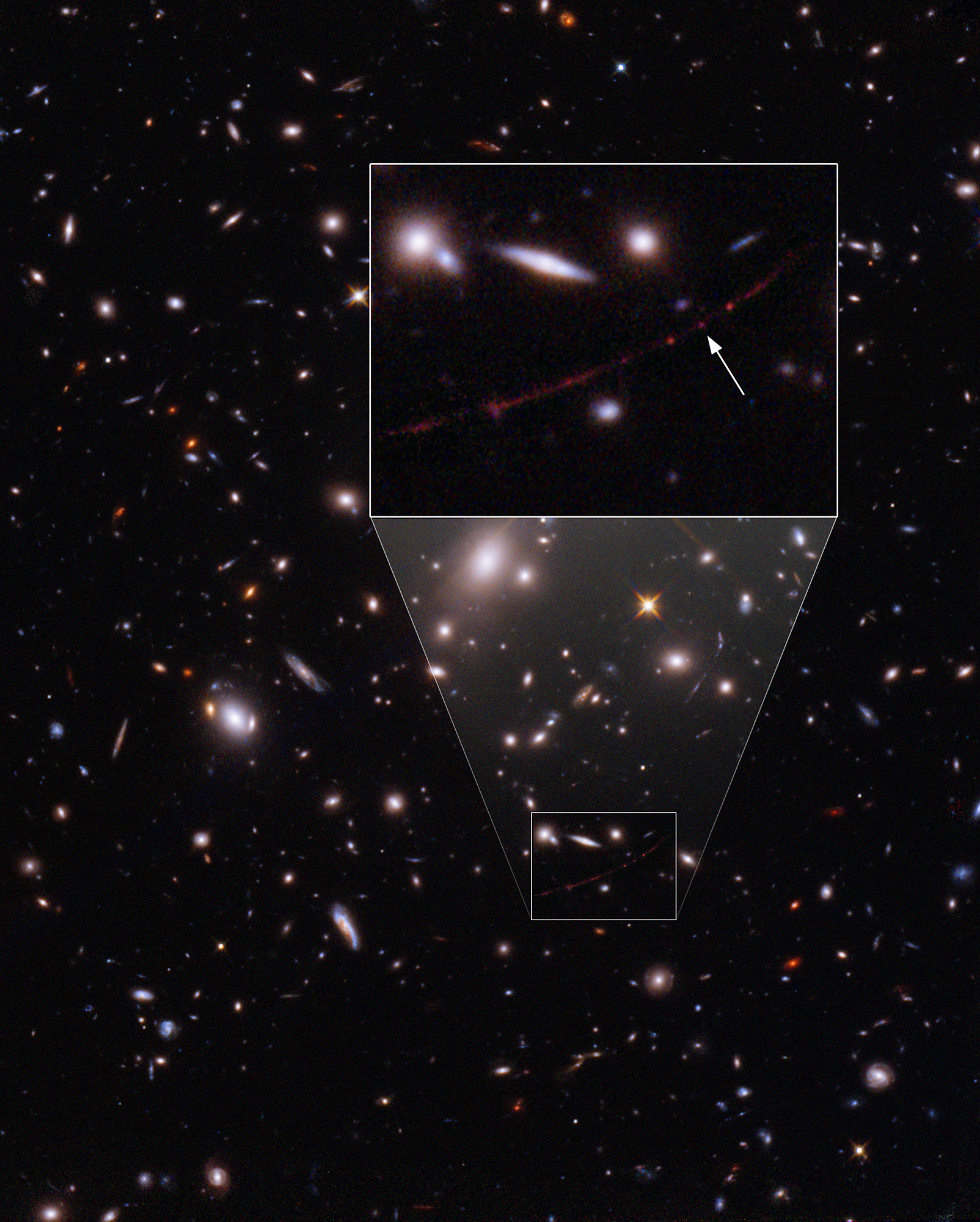

Researchers pouring through high-resolution images of galaxy clusters have found the gravitationally magnified light of a star that was shining just four billion years after the Big Bang. While we’ve seen galaxies that are much further away, this bright star is the new record holder for the farthest star ever spotted. According to Brian Welch: We almost didn’t believe it at first, it was so much farther than the previous most distant, highest redshift star. Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges, with the light from millions of stars blending together. The galaxy hosting this star has been magnified and distorted by gravitational lensing into a long crescent that we named the Sunrise Arc.

Welch is the first author of a newly published paper in the journal Nature.

To understand this discovery, I had to learn some cool new optics, and now, I am here to share all the awesomeness with you, so we can better understand this discovery together.

First, let’s consider the simple concept of “what is a lens.”

I have started wearing glasses and am experiencing the world-warping way progressive lenses bend the world. That, at a certain level, is the most basic definition of a lens — anything that bends light is a lens. Light can get bent as it goes through transparent-ish material like glass, plastic, or even water. It can also happen when light reflects off a surface, like with mirrors. And gravity can bend the path of light.

When a bunch of rays of light from a bunch of different places gets focused together, magnification can occur. This is the basic idea behind gravitational lenses: the gravity of massive systems, like galaxy clusters, can bend a bunch of light rays toward us — light that otherwise would have headed elsewhere in the universe. This added light allows us to see distant objects that would otherwise be far too faint for our current telescopes.

Since we can’t directly observe the earliest galaxies forming or see the first stars, researchers have been looking for the twisted light created through gravitational lensing. The Hubble Space Telescope even conducted a major survey – the RELICS or Reionization Lensing Cluster Survey – to look for these streaks, and it was in the RELICS data that our new star was found.

But it wasn’t just gravitationally lensed like any everyday lens might do; this star’s light fell in a sweet spot that allowed it to be magnified far more than we normally see. That sweet spot is called a caustic, and this is my new vocabulary word for the day.

When light passes through a cup of water or a wavy pool, it can get focused into a set of arcs that come together to create particularly bright points and ripples. These particularly bright areas are called caustics. They don’t teach you about these in your standard undergrad optics class because the math is more than your standard undergrad can handle. I’m glad I’m learning about them now and not then.

All that ugly math and beautiful physics allowed one star, at just the right point, to be amazingly magnified.

But even with this perfect alignment, your run-of-the-mill star wouldn’t have been visible. This star is special in so many ways. Named Earendal, which means “morning star” in old English, it is fifty times larger and millions of times brighter than our Sun. While it’s most likely not a star made of the original mix of hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of lithium and beryllium created by the Big Bang, this star could be that kind of star.

And this tantalizing possibility makes Earendal and its host galaxy, the Sunrise galaxy, a prime target for JWST, when and if it works. Co-author Dan Coe states: With Webb, we expect to confirm Earendel is indeed a star, as well as to measure its brightness and temperature. We also expect to find the Sunrise Arc galaxy is lacking in heavy elements that form in subsequent generations of stars. This would suggest Earendel is a rare, massive metal-poor star.

There are truly beautiful things at the edge of space-time, and it is exciting to finally get to see them.

More Information

ESA Hubble press release

Hubblesite press release

“A highly magnified star at redshift 6.2,” Brian Welch et al., 2022 March 30, Nature