A lot of science boils down to someone, often a student, looking at some data, and someone says something that can be translated to, “Oh that’s weird,” and then a bunch of folks get involved, and a paper is published. A few years later, it starts to be well understood, and if the original researchers are lucky, they may get some cool awards for their one-two punch of being lucky enough to look in the right place or data set and to recognize something worth recognizing is in front of them.

Yesterday, a breaking news story beautifully followed this script. Honors student Tyrone O’Doherty wrote some data reduction routines to look for transient phenomena that come and go in the sky. This kind of software is pretty common for optical and infrared telescopes that search out supernovae and other events, but O’Doherty was using radio data from the Murchison Widefield Array, which looks at the sky in longer wavelengths than earlier telescopes have generally explored. This test platform for technology that will be used in the future Square Kilometer Array is still being pushed to see what it is capable of, and this is where an honors student and some new software come into play.

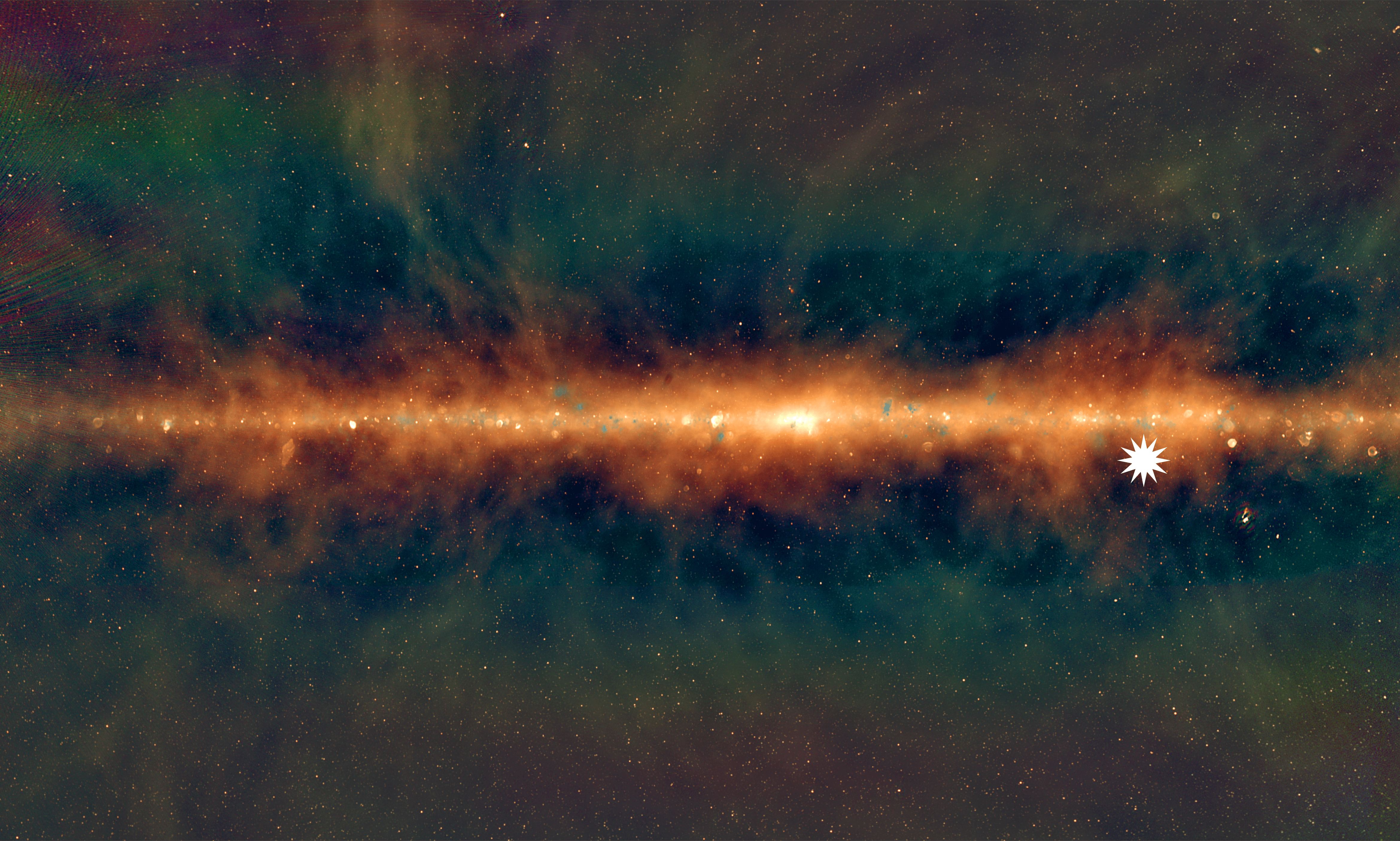

While doing a look-through of archival data, O’Doherty spotted a breathtakingly bright source or at least a source bright in the not well-explored color of radio light Murchison observes. Oddly, this source would turn on for 30-60 seconds every roughly twenty minutes over several hours, and then it would turn off. Or they got unlucky, and the telescope just wasn’t looking during the 30-60 seconds the object was turned on.

In the journal Nature, in a paper led by Natasha Hurley-Walker, the collaboration writes: At the time of writing, the MWA has been in operation for 8 years and this source was only found to be active for 2 months in that time.

They go on to describe how that implies the object is active 2% of the time or sixty days out of the 3,000 searched.

And this brings me to my new favorite published sentence.

This work looked at archival data, so the time sampling they had was at the whim of when other people were looking in that part of the sky for whatever reason, so the telescope wasn’t making continuous observations. This led them to write: Alternatively, we could assume that the source was active any time that we have not thoroughly searched the data and, with the cooperation of a conspiratorial Universe, the duty cycle can trend towards 100%.

To summarize: A student, who is now a Ph.D. student, writes software to look for things that aren’t constant and finds something weird in pre-existing data, and because it was archival data, I can tell you the object is flashing possibly 2% of the time, possibly only flashed during one sixty-day window that happened to be observed or is flashing all the time, and we’re unlucky.

Mysteries are fun, and I expect folks are going to try and sort how to keep a more steady eye – or telescope – on this particular mystery.

Exactly what it is will require more data, but early predictions hint at this being a slow rotating magnetar — a kind of neutron star with an extremely strong magnetic field. These are different from generic pulsars, and it has been predicted that out there somewhere these slow rotating things should be sending out radio emissions.

We just didn’t think one would turn on just 4,000 light-years away and be so bright. Yes, this object is just 4,000 light-years away.

This is going to be an object to follow. Sadly, as close as it is, this is not something my backyard telescope and I can see, but this is a reminder that if you look at that bright star Sirius, you’re also looking at its little white dwarf neighbor.

More Information

ICRAR press release

“A radio transient with unusually slow periodic emission,” N. Hurley-Walker et al., 2022 January 26, Nature