This week in rocket history is another mission of cooperation: the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

In 1968, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Rescue Agreement, which was the follow-up to the Outer Space Treaty signed in the previous year; a document that detailed the rights and responsibilities of nations who put things into space.

Yes, there are treaties that deal with outer space.

One of the main clauses of the Rescue Agreement is exactly what it sounds like: an agreement to return space travelers who land on Earth in a different country to the country they launched from. Also stipulated in the agreement is a requirement that any nation who could assist with a rescue of a crewed spacecraft was obligated to do so.

The Rescue Agreement started additional cooperation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and in 1972, a rescue demonstration was formalized as part of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT), which was an agreement to limit the number of nuclear missiles on both sides. The early plan was to dock an Apollo to one of the Salyut stations, but that plan was abandoned early on because it was too expensive to add a second docking port to the current station at the time. Instead, an Apollo would meet with just a Soyuz capsule in orbit.

One of the key problems of docking the Apollo and Soyuz capsules is the atmospheres of the two capsules. You see, the Americans played rock and roll while the Soviets played classical music. [crickets]

Actually, the problem was the Soyuz capsule was pressurized with a mix of oxygen and nitrogen at 14 psi while the Apollo used pure oxygen at 5 psi. Directly mixing the atmospheres would have caused problems. Suddenly changing external pressure around a human body is a bad idea if you want to keep those humans alive. So Soviet and American engineers designed a Docking Module as an airlock for a proper equalization of atmospheres and for the Apollo to dock to the Soyuz.

The other major problem they had to overcome was incompatible docking systems.

After iterating through many designs that included ones with several cones and others with four petals, they settled on one with three petals that faced outwards spaced 120 degrees apart called APAS-75 or Androgynous Peripheral Attachment System-1975. It could act as both an active and a passive docking port with the same hardware, depending on the configuration of six pistons which dampened docking forces.

The active spacecraft approached with the petals extended by the six pistons, while the other spacecraft retracted a ring in the system. Once the petals on the two spacecraft meshed together, the active spacecraft retracted its ring, and the two spacecraft secured the connection with some bolts. The system was tolerant of slight misalignment, with hydraulic pistons that could extend or retract to make sure the alignment was within tolerances even if it wasn’t perfect.

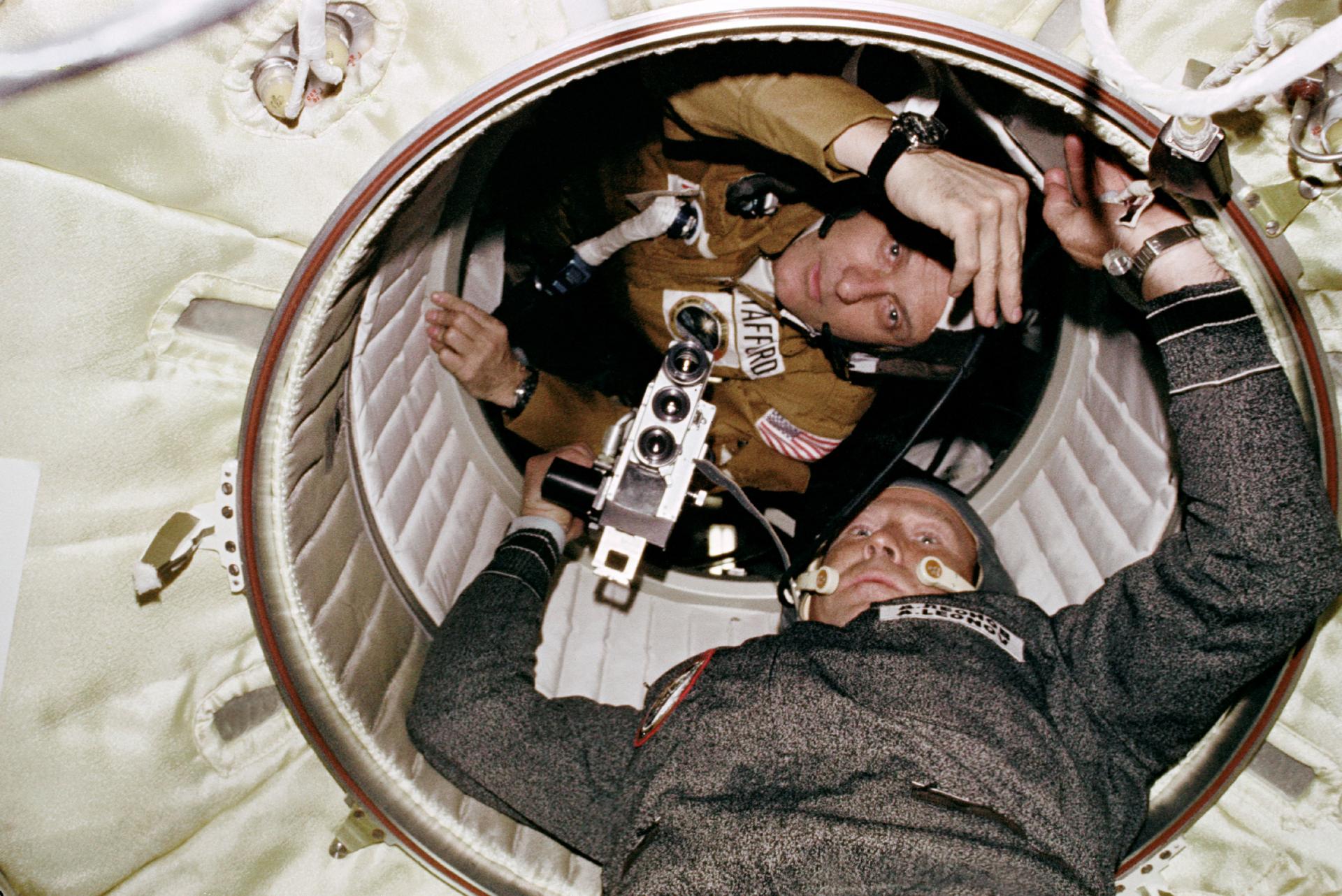

Another problem was fitting this docking port inside the fairing of the Soyuz rocket. Changing the fairing to accommodate a wider docking port would have changed the aerodynamics of the rocket and required expensive requalification of its flight profile. The Soviet design principle is essentially one of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”, so the port ended up smaller than the American-preferred, 90-centimeter tunnel. The port was limited to a maximum external size of 130 centimeters, with a maximum inner diameter of only 80 centimeters through which the astronauts had to pass. That’s about 40 percent bigger than a typical manhole cover. Despite the very tight fit, they were able to use it in a shirt-sleeve environment, but not a bulky spacesuit.

The crews of the Apollo and Soyuz trained for the mission in both Houston and Star City near Moscow. The Apollo crew was announced in 1973 as Tom Stafford, Eugene “Deke” Slayton, and Vance Brand. The Soyuz crew was Valeri Kubasov and Alexei Leonov. The NASA personnel and journalists became the first Americans to go to the secret cosmonaut training center, which didn’t appear on any official maps at the time.

In 1975, everything was ready. The Soyuz launched first at 12:20 UTC on July 15 from Baikonur. Seven and a half hours later at 19:50 UTC, the Apollo launched from Kennedy Space Center. The docking module was brought up with the Apollo on its Saturn 1B rocket in the space underneath the service module where the Lunar Module would be for a lunar mission.

Two days after the launch of Apollo, the two spacecraft docked at 16:10 UTC on July 17. After a slight delay due to a concern with the atmosphere in the docking module, specifically the “strong scent of burned glue”, Astronaut Brand opened the hatch to the Soyuz at 19:17 UTC.

When the five astronauts were settled, U.S. President Gerald Ford spoke to them from the White House, asking many questions about their experiences and congratulating them on their achievements. After the call, the crew exchanged gifts and a meal.

The next day the combined crews began with giving televised tours of their respective spacecraft with the Americans speaking Russian and the Russians speaking English. Another part of the TV broadcast involved zero-g science demonstrations for school children in both countries.

On July 20, 1975, the fifth day of the mission, the two spacecraft undocked at 12:12 UTC, and the Apollo backed away a few tens of meters. The spacecraft remained aligned along their axes, and the Apollo served as an improvised coronagraph for the Soyuz crew to take pictures of the Sun’s corona. At the same time, ground-based solar telescopes conducted observations allowing them to be compared later with and without atmospheric disturbance.

They docked again at 12:55 UTC with the Apollo acting as the active vessel, as it had the first docking.

Apollo deorbited at 20:37 UTC on July 24, but they almost didn’t make it to the surface alive; however, I’m happy to report that the three crew members survived the re-entry.

Overall, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Program was a successful mission for both countries that would lead to future cooperation between the two superpowers. It was also a technological dead end, with the APAS-75 port never being used again. Science – in the name of peace.

More Information

ASTP Overview (NASA)

SP-4209 The Partnership: A History of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (NASA)

Join the Crew!

Join the Crew!

Escape Velocity Space News

Escape Velocity Space News

0 Comments