This week in Rocket history was kinda boring, if we’re being honest. Nothing seems to have happened in the first week of April! The second week of April, however? Oh boy!

So this week, we’re taking a look at next week in history – specifically, April 12.

On the morning of April 12, 1981, astronauts John Young and Robert Crippen launched from the Kennedy Space Center to a low-earth orbit at an altitude of 244 by 276 kilometers. They were: the first Americans in space since 1975’s Apollo-Soyuz; the first crewed American mission to launch atop Solid-fuel Rocket Boosters; and most importantly, the first-ever orbital Space Shuttle mission.

The launch of Space Transportation System-1, better known as STS-1, was actually supposed to take place two days earlier, but it was scrubbed due to a software issue with one of theIBM System/4 Pi computers on board, which was solved with a software patch before the launch on April 12.

It’s important to note that the term “Space Shuttle” doesn’t actually refer to the spacecraft itself but rather to the entire assembly of the craft, the external fuel tank, and the solid-fuel rocket boosters, or SRBs. The spacecraft itself was referred to as the Orbiter, and along with the SRBs, was designed to be reusable. The large external fuel tank was the only major component of the program that wasn’t reusable.

The orbiter for STS-1 was the OV-102 Columbia, one of five orbiters that would end up flying in space (and another which didn’t: the OV-101 Enterprise).

STS-1’s original mission was not actually supposed to be an orbital insertion. It was supposed to be a test of its Return-To-Launch-Site abort plan, which would simulate a failure in the shuttle’s system shortly after launch. The Orbiter would dump the SRBs and return to the launch site by flipping around while the main engines were still burning. Young vetoed the plan, saying: Let’s not practice Russian roulette, because you may have a loaded gun there.

The mission was also the first time a crewed American space vehicle was flown withoutfirst being tested autonomously. It was Young and Crippen’s mission to actually verify that the spacecraft was functioning as expected, and the only payload for the mission was a set of instruments meant to determine the craft’s performance.

The launch itself went with only a few anomalies; the SRBs turned out to perform better than anticipated, giving the orbiter a much higher acceleration than originally planned but still within parameters.

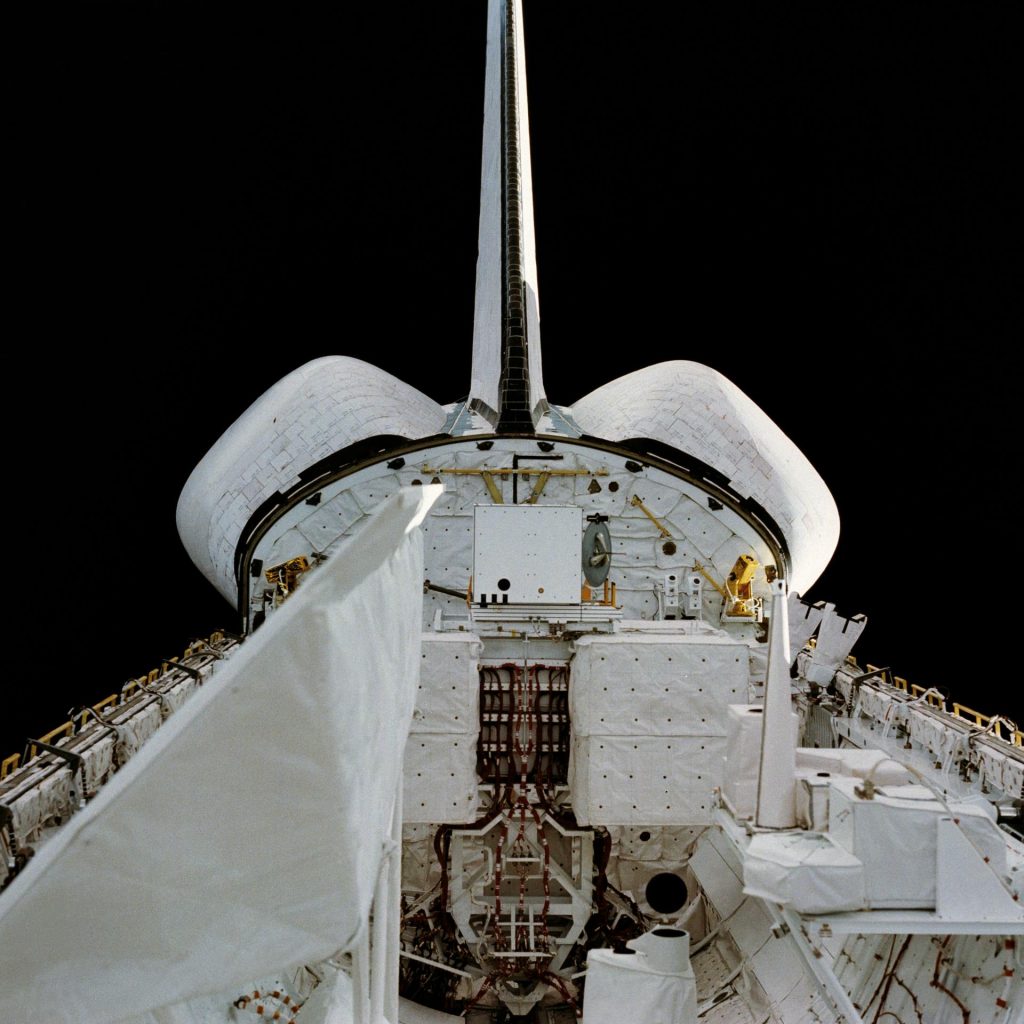

Once in orbit, the crew opened the Orbiter’s cargo bay door in order to expose the radiators mounted on the inside of the doors to space to expel heat from the spacecraft. Had this cooling system not worked, they would have needed to return immediately as a build-up of heat would have jeopardized the mission, but fortunately, they didn’t need to.

When the doors were opened, the crew noticed damage to the thermal protection tiles next to the orbiter’s main engines. Sixteen tiles were missing and another 148 were damaged. Ground control examined the footage and determined that the missing and damaged tiles would not risk the structural integrity of the craft during re-entry and were therefore not a cause for concern.

Another small issue was with the cabin’s life support systems. They were within safety parameters but they didn’t maintain temperature and air pressure as expected. The astronauts reported colder than expected temperatures on the first night of their mission, but they managed to adjust the settings to get a more comfortable temperature the second night.

After 53 hours in orbit and once all of their tests had been completed, Young and Crippen started preparing for re-entry. They closed the payload bay doors, strapped into their seats, and prepared for the mostly autonomous re-entry process. The orbiter’s engines fired for 160 seconds, after which Young had to manually pitch Columbia to its correct attitude. They armed their ejection seats, and the rest was left to gravity and aerodynamic resistance.

At an altitude of about 100 kilometers, the crew started seeing jets of plasma caused by the friction of the orbiter’s heat shields against the thickening atmosphere. When the air pressure was high enough for the craft’s aerodynamic systems to work, the orbiter performed a right bank in order to increase drag and slow the craft even more (even though at this point it was going over Mach 24 or a bit over eight kilometers per second!) Columbia then performed a left bank at Mach 18.5, another right one at Mach 9.8, and then Young himself performed two more bank reversals at Mach 4.8 and 2.8.

Young and Crippen were now flying towards Runway 23 at Edwards Air Force Base, and as they went subsonic they were joined by a T-38 flown by fellow astronauts Jon McBride and George Nelson. They flew in formation until Columbia touched down at 17:21 UTC at a speed of 399 km/h, with Young remarking over the radio: This is the world’s greatest all-electric flying machine. I’ll tell you that. That was super!

More Information

PDF: Space Shuttle Missions Summary (archive)

The Space Shuttle’s Controversial Launch Abort Plan (Tested)

STS-1 (NASA)

Join the Crew!

Join the Crew!

Escape Velocity Space News

Escape Velocity Space News

0 Comments