As a space and astronomy news program, we don’t generally have to worry about relaying too much depressing news. There is the occasional exploded rocket or satellite that misses an orbit, but except for the thankfully rare loss of life among astronauts, what we talk about is fairly upbeat.

But then there are days like today when we’re reminded that Earth is a planet, and as we cover our own world from a scientific standpoint, things aren’t always that great.

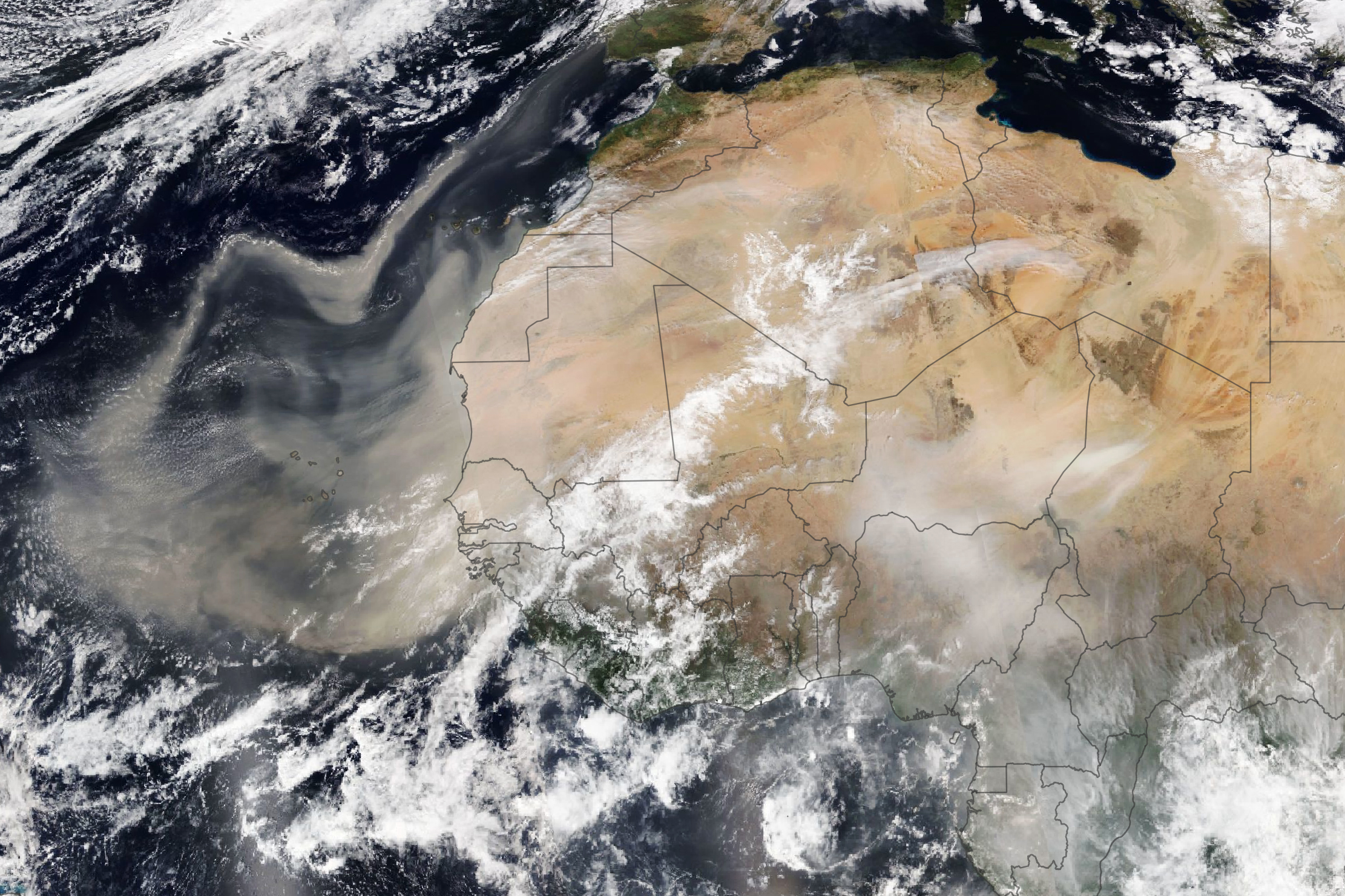

In the past, we’ve talked about planet-obscuring dust storms on Mars, and now, we have Earth images from the NOAA-20 spacecraft depicting continent-obscuring dust here on Earth. Those of you living in Europe may already know from your weather forecasts that a massive dust plume, stirred up across Northern Africa, and is now sending dust out over the Atlantic Ocean and northward toward Europe. This wider perspective image from the DSCOVR satellite shows more of that dust as a beige cloud sweeping off the African continent.

While the images are eerily beautiful and make for neat comparative science between Earth and Mars, they point to a more human tragedy. In southern France, the air is dense with fine particulates, and the sky is beige from the dust blocking out the sky. This dust is significantly more intense than past dust storms, and this doesn’t bode well for folks living at the base of the Alps. This dust, as it settles out of the air, coats everything, including the snow, which will then melt more readily and melt earlier in the season.

In the past, these kinds of dust plumes have even carried microbes from the Sahara to the glaciers of the Alps. According to the Barcelona Dust Forecast Center, this weekend Saharan dust is expected over the Iberian peninsula and the western Mediterranean. Looking at these forecasts, I’m kind of glad that wearing masks is becoming more normalized; this isn’t something you want in your lungs, and unfortunately, these kinds of dust events are likely to also become the new normal.

As our planet’s carbon dioxide levels rise, and with it the temperatures, we’re seeing the oceans and land driving winds in new ways. In Texas, these changes led to a massive arctic blast last week, as the jet stream failed to trap the arctic cold in the Arctic.

New research from Jordan Abell that appears in the journal Nature tries to understand just how the winds are changing by studying what the earth was like last time carbon dioxide and temperatures were this high. That last time? It was the Pliocene epoch, three million years ago, that time when early hominids were emerging and giant mammals still wandered the Earth. Looking at the geologic record to see where the wind carried dust during that time period, this research team discovered that Earth’s westerly tradewinds migrate more northward as the temperatures warm.

There is no way to know on what timescale things will change, but over time, perhaps centuries, this change in the wind will mean less rain for North America, Europe, parts of Australia, and New Zealand. Where things grow will change, and deserts will migrate. This has happened before, but this is the first time such change has been so rapid, and the next question becomes, can life adapt quickly enough to the changes that are coming.

Changes in rainfall and winds are just some of the factors that affect forecasts for fire season. New research from Steven Brey and company appearing in Earth’s Future, indicates that figuring out just where fires are likely to break out and how widespread they can become is more complicated than anyone would like.

The primary indicator of if it will be a bad fire year is the vapor pressure deficit; this is the difference between how much moisture is in the air and how much moisture could be in the air if it were saturated. While dry air generally leads to more fire, the devil is in the details, and those details include precipitation, evaporation, relative humidity, root zone soil moisture, and wind speed.

In trying to understand how widespread fires will be in the future, this team concludes, and here I quote from the paper: We show that increases in burn area are likely as many climate models suggest the future will be drier. However, we find that future wildfire burn area estimates are lower whenever and wherever the importance of aridity is reduced.

Put another way, if we let our land dry and see a reduction in plant life and agriculture, more will burn. If we want to offset the effects of climate change, we need to find ways to maintain soil moisture as rains recede.

Climate change doesn’t affect just the landscape. It also has a huge impact on life in cities, and unfortunately, studies are finding that how someone is affected is strongly biased by an area’s poverty levels, and those generally reflect racial divides.

In trying to mitigate the worst effects of climate change, the United Nations has devised a series of global goals that should both improve quality of life and improve our world’s future. A new study looks at how we’re doing with respect to three of these goals, which include providing everyone with access to affordable public transport, adequate waste management systems, and green spaces.

To measure what was going on, researchers combined data from OpenStreetMap on transport and used satellite data to study green spaces and waste handling. By combining this data with demographic information, it became possible to understand where problems may arise, and the answer was everywhere. No city over ten million had equal access to people of all demographics, and very few smaller cities scored highly in both environmental performance and inclusivity. Those few exceptions included Freetown, Sierra Leone; Darwin, Australia; and San Jose, California.

To quote from a summary of this research prepared by Eos: More than half of the 164 cities fell into the category of good overall performance but with lower-income neighborhoods bearing a disproportionate share of environmental burdens. … Reasons for these inequalities are linked with local contexts. In inner-city communities, air pollution is often worse, and a lack of tree cover and green space can result in dangerously high summer temperatures through the urban heat island effect.

Essentially, as too often happens, the worst effects will be lived by those least able to afford to find solutions. As a global civilization, we need to do better to ensure we provide all humans an equal chance to at least have a cool green space to escape to. We’ll include links to the full dataset on our website, DailySpace.org.

More Information

Dust Heading For Europe and Dust Systems Shifting Due to Climate Change

- NASA Earth Observatory article

- Eos article

- “Poleward and weakened westerlies during Pliocene warmth,” Jordan T. Abell et al., 2021 January 6, Nature

Analyzing Environmental Predictors of Western U.S. Wildfires

- Eos article

- “Past Variance and Future Projections of the Environmental Conditions Driving Western U.S. Summertime Wildfire Burn Area,” Steven J. Brey et al., 2020 July 17, Earth’s Future

A Look at Natural Hazards, Climate Change, Urban Living, and Equity

- Natural Hazards Have Unnatural Impacts—What More Can Science Do? (Eos)

- Where Do People Fit into a Global Hazard Model? (Eos)

- Dangerous Heat, Unequal Consequences (Eos)

- Using Big Data to Measure Environmental Inclusivity in Cities (Eos)

- “Measuring What Matters, Where It Matters: A Spatially Explicit Urban Environment and Social Inclusion Index for the Sustainable Development Goals,” Angel Hsu et al., 2020 December 14, Frontiers in Sustainable Cities

Join the Crew!

Join the Crew!

Escape Velocity Space News

Escape Velocity Space News

0 Comments