Beneath the surface of the Earth, methane gas is intermixed with water, forming pockets of methane hydrate. Basically, the surface pressure is high enough that the gas is kept locked in between the water molecules. It’s what we call “thermogenic methane” because it’s produced directly by geological processes deep underground. This is opposed to the biogenic methane we all know from methanogenic archaea in the guts of animals like cows (and some people… thank you, Mary Roach). Anyway, methane, of course, is a greenhouse gas, and that is a huge concern these days.

The methane that is nicely locked underground can come bursting or seeping out if the pressure on that ground decreases. And the pressure can decrease for several reasons, one of which is the loss of Arctic ice sheets and their tremendous weight. It’s definitely a negative feedback loop, and scientists are seeking to understand just how big a problem this could be in the near future. So a team took several sediment core samples off the coast of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean to see how methane was released at the end of two periods of ice sheet loss.

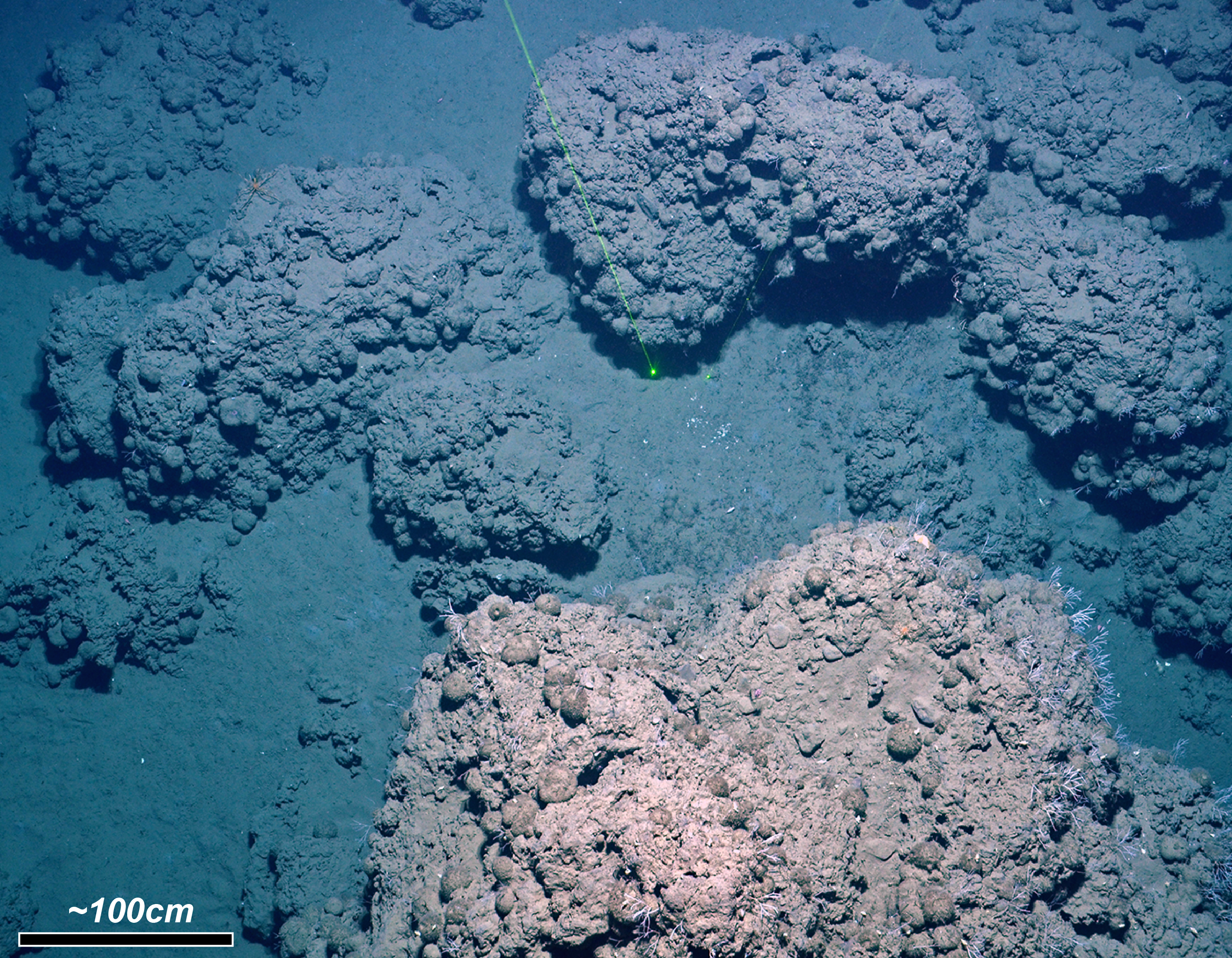

Methane is one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms, so when it’s released, carbonate-loving critters like foraminifera thrive and build shells with even more carbon-rich content than usual, and that carbon content can be tracked over time in the cores to see when the amount of methane changed. They found that as the ice melted, the pressure lessened, and methane was released in both violent bursts and slow seeping. Once the ice melted, the release of methane stabilized, but just how much methane was released in each episode is unknown. Since there are methane-loving critters, the methane is consumed and the calculations are complicated.

In fact, the team found massive layers of bivalves (think clams and oysters) in the cores, which confirms modern observations that these animals create massive communities around methane leaks. So while the methane release isn’t good for us, it is great for some seafloor critters. This work is published in the journal Geology with lead author Pierre-Antoine Dessandier.

More Information

GSA press release

“Ice-sheet melt drove methane emissions in the Arctic during the last two interglacials,” P.-A. Dessandier et al., 2021 March 22, Geology