Space is hard, and some days, getting rockets to work doesn’t go as well as expected. An Epsilon rocket launched by JAXA and carrying eight payloads including RAISE 3 was lost when mission control triggered the flight termination system due to an attitude issue. Plus, stars blowing dust rings, stars exploding, asteroids getting hit with spacecraft, and Europa’s geysers may not come from the subsurface ocean.

Before we get started today, we want to remind you that CosmoQuest-a-Con is coming up this weekend, October 21 through 23. We have an amazing docket of guests, vendors, contests, and general science shenanigans, all taking place virtually on Twitch and Discord. So bring your potato shaped like an asteroid, set up your Minecraft login, and grab your tickets for this year’s three-day fest of science and creativity. To learn more, go to CosmoQuest.org and click on the CosmoQuest-a-Con banner.

Podcast

Show Notes

Binary stars shape dust into rings

Supernova early warning system developed

- RAS press release

- “Explosion imminent: the appearance of red supergiants at the point of core-collapse,” Ben Davies, Bertrand Plez, and Mike Petrault, 2022 October 13, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Massive stellar explosion blasts out gamma rays

- NASA Goddard press release

DART changes Dimorphos’ orbit!

- NASA press release

Astronomers observe Lucy from Australia

- Curtin University press release

- VIDEO: Lucy Flyby

InSight lander faces winter dust storms

- NASA JPL press release

Europa’s eruptions likely from shallow surface lakes

- NASA press release

- NASA JPL press release

- “Simulation of Freezing Cryomagma Reservoirs in Viscoelastic Ice Shells,” Elodie Lesage, Hélène Massol, Samuel M. Howell and Frédéric Schmidt, 2022 July 21, The Planetary Science Journal

JAXA triggers flight termination of launch

- JAXA press release

China sends up another radar satellite and three Yaogan sats

- China launches new environmental satellite (Xinhua)

- China successfully launches new remote sensing satellite (Xinhua)

SpaceX launches Hotbird 13F satellite for Eutelsat

- Eutelsat press release

- Eutelsat Hotbird 13F mission page (SpaceX)

Crew Dragon Freedom returns after 170 days at ISS

- SpaceX press release

Transcript

As human beings, our team just needs to sometimes take a week off, and last week was our week to catch our breath, go out, and catch some light from our nearest star, then work on some projects that otherwise just don’t get enough attention.

And, during our week off, all sorts of amazing things happened, and today we’re going to try and cram a lot of news into not enough minutes. We have stars blowing dust rings, stars exploding, planets preparing to have geysers, rockets going up, and rockets failing to go up.

Hold onto your seats; we’re going to talk fast as we bring you all this and more, right here on the Daily Space.

I am your host, Dr. Pamela Gay, and we are here to put science in your brain.

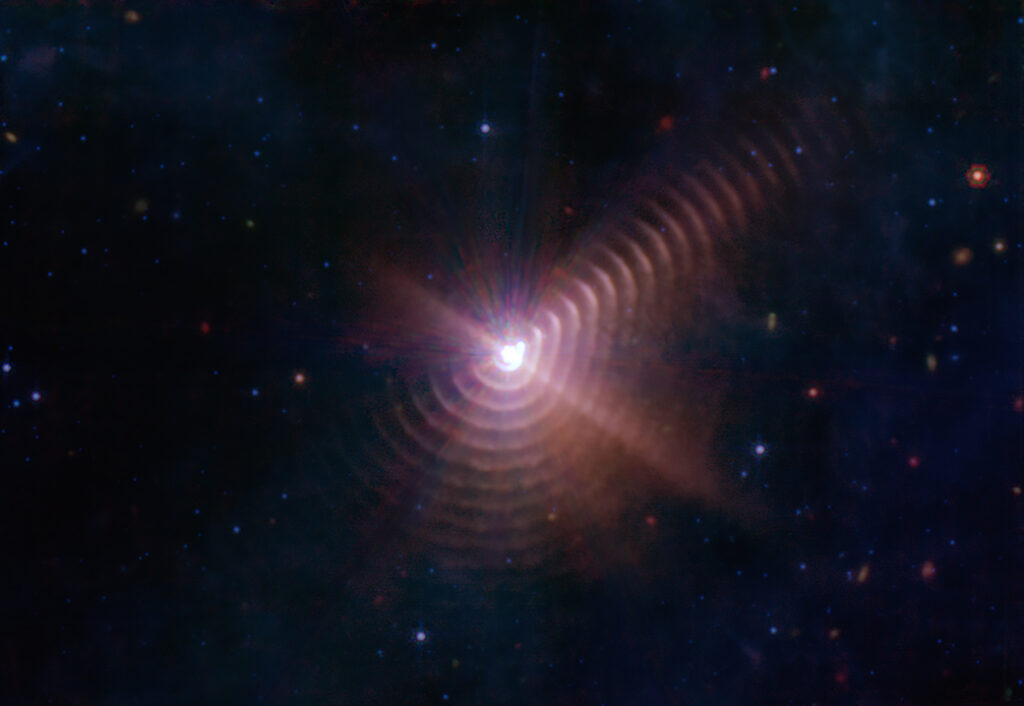

A few weeks ago, we brought you a stunning image produced by Judy Schmidt using brand-new images from JWST. At the time, we didn’t know exactly what science would come from that data, and I thought we’d be waiting until Christmas to get an explanation of how these rings formed.

Well, I’m super pleased to say I was super wrong. Those science results came out in the latest issue of Nature in a paper led by Ryan Lau.

Here is what they report we’re seeing: at the core of at least seventeen concentric dust shells are two stars – a carbon-rich Wolf-Rayet star (WR 140) and a hot O-type star. These two massive stars are in a highly eccentric orbit that brings them close together every 7.93 years. Like all Wolf-Rayet stars, WR 140 is generating dust, but instead of shedding it fairly continuously, the dust is blasted off by its hot companion every time they sweep past each other.

The seventeen shells we see were emitted over 130 years. These rings contain carbon-rich dust and organic molecules formed with the carbon from the star.

Rarely do we get to see anything happen on human time scales, but the short-lived massive stars are giving us a rare and wonderful show we can actually watch evolve. Here is where I hope that JWST functions long enough to allow us to see new shells form and evolve over several 7.93-year cycles.

Massive stars like those in WR 140 burn through their fuel quickly and have the potential to end their lives as brilliant supernovae. Right now, the red giant Betelgeuse is rising in the late evening. Of all the stars we can see with our eyes, Betelguese is the one closest to going supernova, but in all likelihood, it won’t go boom for many hundreds of thousands of years.

When we start using telescopes, however, there are a whole lot more stars to see and potentially see explode. The trick is figuring out which ones we need to watch.

A new paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society led by Benjamin Davies, however, gives us an early warning sign to watch for. According to this paper, red giants will shed their outermost atmosphere, and this material will hide their light, making them appear a hundred times fainter in visible light.

Now we just need a survey focused on looking for stars that fade away so we can focus on them to catch every stage of the soon-to-erupt supernova.

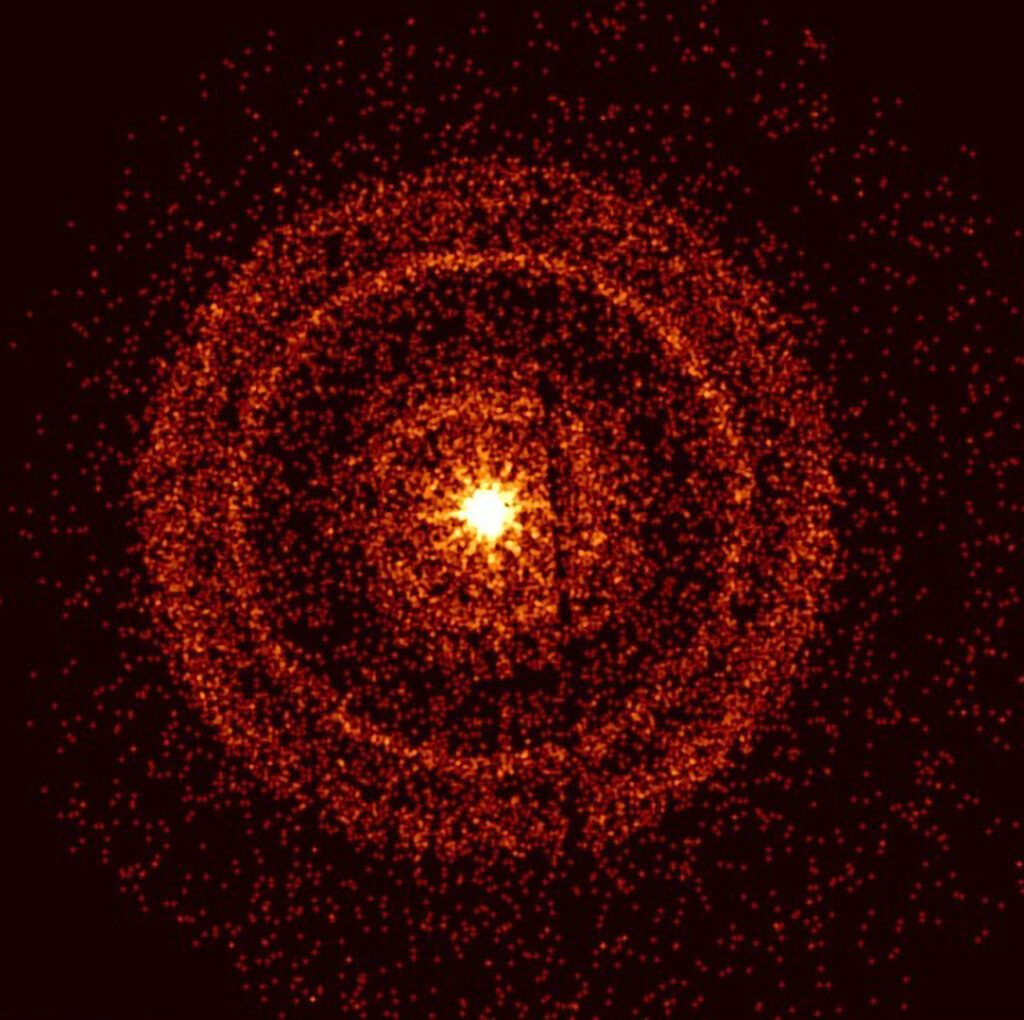

This new early warning system, however, couldn’t have warned about the massive gamma-ray burst that was detected on October 9. We know detailed science papers will be coming in the near future. For now, here is what we know: a wave of high energy light – X-rays and gamma rays – swept across the detectors of Fermi, Swift, Wind, and NICER. Telescopes around the work quickly turned to the source, and imaging revealed a fast-fading point of light shining from what we assume was a star dying 1.9 billion years ago. In the grand scheme of the universe, 1.9 billion light-years away is right next door, and the images captured in the ten hours after the first detection are going to reveal never-before-seen details to serve as a check on our models of how gamma-ray bursts should behave.

And this wasn’t any gamma-ray burst. According to Roberta Pillera, a Fermi-LAT collaboration member: …it’s also among the most energetic and luminous bursts ever seen regardless of distance, making it doubly exciting.

I really look forward to all the new science this high-energy event is going to bring us, and when it is published, we’ll bring it to you here at the Daily Space.

For now, though, we’re going to switch gears and look at the goings on around our solar system.

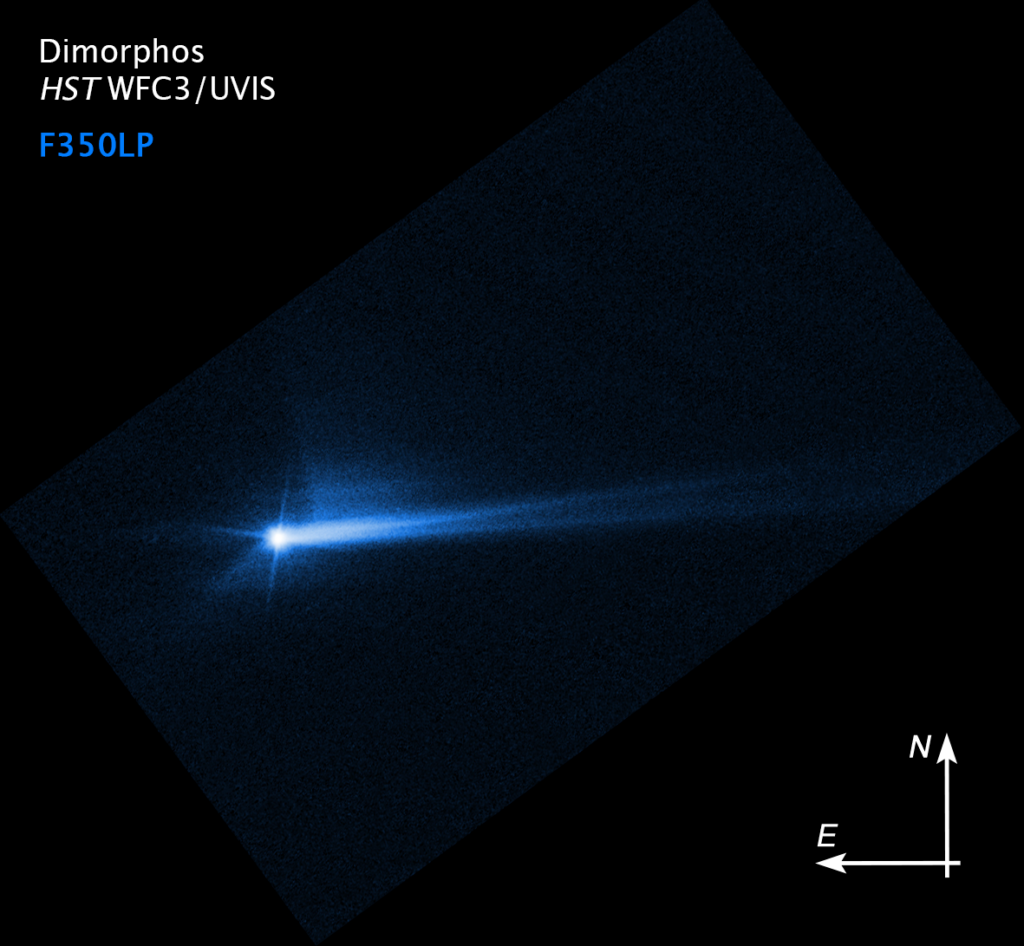

One of the biggest planetary stories from last week was the announcement by NASA of the preliminary results of the DART mission’s impact of asteroid Dimorphos. With much fanfare and a press conference, NASA shared that the spacecraft altered the asteroid’s orbit, successfully completing the first full-scale demonstration of this particular form of planetary protection.

I’m pretty sure most of the science community expected that we managed to alter an asteroid’s orbit after witnessing the amazing puff of material and 10,000-kilometer-long trail of dust. What was not expected was the degree to which Dimorphos’s orbit was altered. The minimum success for this mission was a whopping change of at least 73 seconds. Seconds. Dimorphos orbits Didymos in 11 hours and 55 minutes, which means 73 seconds isn’t a very big difference.

However, after careful measurements by the investigation team using a variety of ground telescopes, Dimorphos’s orbit was calculated to be 11 hours and 23 minutes – a change of 32 minutes. Minutes, not seconds. Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, notes: This result is one important step toward understanding the full effect of DART’s impact with its target asteroid. As new data come in each day, astronomers will be able to better assess whether, and how, a mission like DART could be used in the future to help protect Earth from a collision with an asteroid if we ever discover one headed our way.

Pretty impressive for a first demonstration. We look forward to more results over the coming months and years as the data is analyzed and when ESA’s Hera spacecraft arrives to conduct detailed surveys of the system.

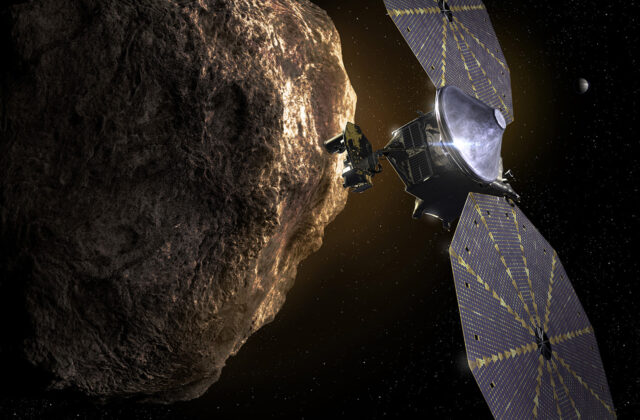

In other asteroid mission news, researchers at Curtin University were asked by NASA to make observations of the Lucy spacecraft over this past weekend. Lucy is on its way to observe a handful of asteroids known as Trojan asteroids that are orbiting in two of Jupiter’s LaGrange points.

Planetary scientist Eleanor Sansom explained that Curtin’s Desert Fireball Network would capture footage during a close pass of Lucy on Sunday, October 16. She noted: After traveling at about 108,000 kilometers per hour around the Sun, Lucy will come back towards the Earth this weekend for the spacecraft’s first gravity assist since launching on October 16, last year.

The video capture was a success for the team, and we’ll have a link to their video in our show notes at DailySpace.org.

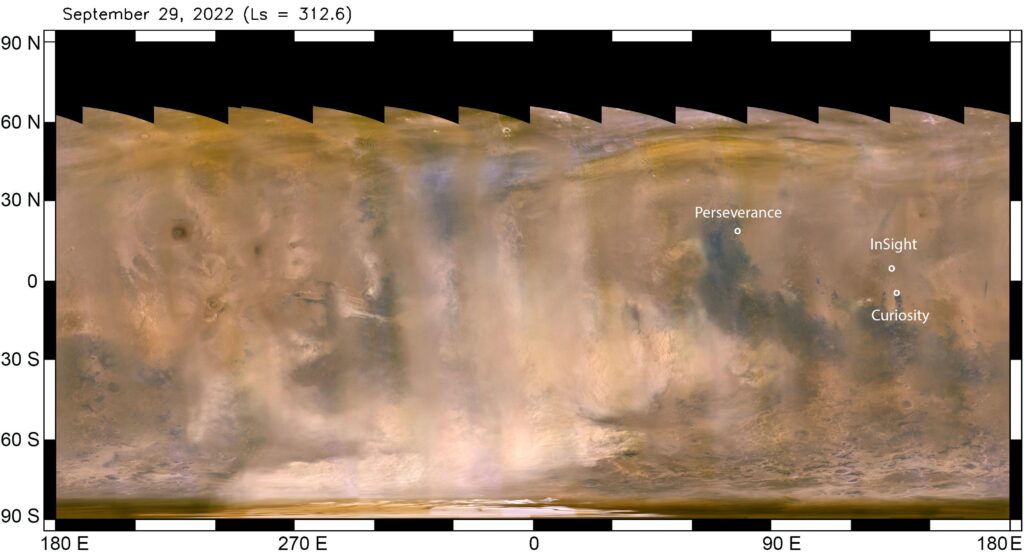

Another mission we’re keeping an eye on is NASA’s InSight. The can-do lander which was plagued by a variety of issues but kept on ticking and tracking wind and quakes is approaching the end of its mission as dust continues to collect on the solar panels. A recent dust storm that started out 3,500 kilometers away from the lander in September became a global storm that eventually increased the haze by 40% over InSight.

Sadly, this means that with even less solar power, InSight’s seismometer has been turned off for a couple of weeks. Project manager Chuck Scott is cautiously optimistic, saying: If we can ride this out, we can keep operating into winter – but I’d worry about the next storm that comes along.

The lander has already far surpassed its primary mission and has been well into its extended mission, measuring marsquakes and learning more about the martian interior. While we’ll be sad to see InSight’s mission end, we are excited to see what breakthroughs the already collected data will continue to bring.

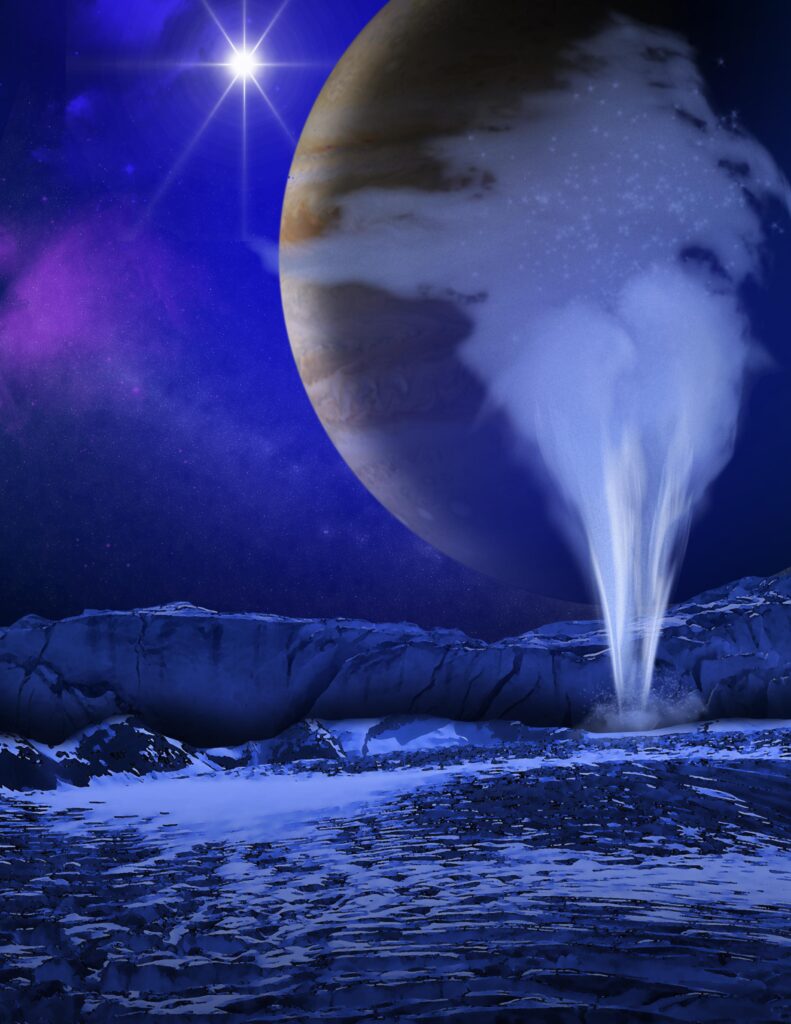

Moving farther out into our solar system, we turn now to Jupiter’s moon Europa, which likely has a global subsurface ocean that could be habitable. For that reason, NASA is sending the Europa Clipper spacecraft to collect data on the icy moon and possibly even sample some of the plumes that erupt from the surface. Now, in a new paper in the Planetary Science Journal led by Elodie Lesage, computer models of Europa support the hypothesis that those plumes could be a vapor or some type of flowing slushy ice.

And if those types of eruptions are occurring on Europa, they probably come from ‘shallow, wide lakes embedded in the ice’ rather than from the subsurface ocean. Lesage explains: We demonstrated that plumes or cryolava flows could mean there are shallow liquid reservoirs below, which Europa Clipper would be able to detect. Our results give new insights into how deep the water might be that’s driving surface activity, including plumes. And the water should be shallow enough that it can be detected by multiple Europa Clipper instruments.

The models suggest that the eruptions come from reservoirs in the uppermost four to eight kilometers of the crust. At this depth, the ice that essentially encases Europa is at its coldest and most brittle, and as those pockets of water freeze, they expand and cause cracks in that ice. Those cracks then lead to eruptions, allowing the pockets of water to burst out in wide, flat swathes.

Deeper reservoirs would push against the warmer surrounding ice, which then acts like a cushion and absorbs the pressure of expansion rather than cracking and erupting.

To really understand just what is occurring with these eruptions, we will have to wait for Europa Clipper to arrive in 2030 and take observations of the surface during its roughly fifty flybys. I’m still rooting for space whales.

And now, rocket news with Erik Madaus.

We were off last week, so the launches that we would have talked about on last Tuesday’s show were written up for the website instead. You can go there to read all about them, including a SpaceX launch that wasn’t a batch of Starlink, and even a Chinese launch from an ocean platform.

Let’s start with the not-so-good launch. On October 11 UTC (October 12 in Japan), a Japanese Epsilon rocket launched the RAISE 3 mission from the Uchinoura Space Center in southern Japan.

The JAXA webcasts are always fun to watch, and this was no different, with the three hosts talking excitedly about the payloads on the mission with the rocket itself in the background.

This was the sixth flight of an Epsilon rocket overall and the fifth of the Epsilon S variant. The eight payloads included the rapid innovative payload demonstration satellite (RAISE), three primary satellites, and two radar satellites for the Japanese company IQPS. Rounding out the satellites onboard were five CubeSats from Japanese universities.

The all-solid vehicle took off from the pad right on schedule, and all appeared nominal through first-stage burnout. The webcast continued on through the point of third-stage ignition, showing a map of the rocket’s track.

Then, the webcast unexpectedly switched back to the empty pad at the scheduled time of the third-stage ignition. The no-longer-excited hosts came back on to announce the end of the webcast and told viewers to look for updates on JAXA’s website. None of which is a good sign for a launch.

A post-launch press conference confirmed that the telemetry showed the rocket’s attitude was wrong at the moment of the first-stage shutdown. Instead of having the rocket go off course, JAXA triggered the flight termination system prior to separation and ignition of the next stages.

Now about those satellites that should have been put into orbit.

Like RAISE 1 and 2, RAISE 3 was developed to test a variety of small instruments on one platform. RAISE 3 contained seven instruments, including a transmitter for Internet of Things devices, a new thruster that used water as a propellant, and a deorbit sail sized for microsatellites.

QPS SAR 3 and 4 were supposed to be the first operational satellites for IQPS’ constellation.

The five university CubeSats included two that were going to test proximity operations between smallsats, useful for Earth observation; one that was testing off-the-shelf parts for semiconductors in space; and one that was 3D printed as a single piece; and one that was going to study the Earth’s crust under the sea floor.

The next day, on October 12, in the same part of the world, a Chinese Long March 2C launched the S-SAR 01 satellite into orbit from the Taiyuan launch center in China. S-SAR 01 is a radar satellite that will produce five-meter resolution imagery for the Chinese government’s Ministry of Emergency Management and Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

According to the China National Space Administration, the satellite will be used for disaster relief, environmental protection, and natural resource management. The latter includes agriculture, water conservancy, and forestry.

On October 14, China also launched three Yaogan satellites from the Yaogan 36 series on a Long March 2D. The Yaogan series typically have military purposes so not much was said about the launch other than it was successful.

SpaceX continued a string of launching other people’s satellites with Hotbird 13F on October 15.

Eutelsat of France contracted SpaceX to launch several new C-band communication satellites before December 2023. Their first satellite launched this week, Hotbird 13F. Hotbird 13F and its sister satellite 13G will replace three older satellites at the 13-degrees East position.

Hotbird 13F launched on Booster 1069 from SLC-40 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Booster 1069 was on just its third flight and successfully landed on the drone ship Just Read The Instructions nine minutes after launch. There was no spectacular plume like a previous launch, but the webcast managed to show video for most of the landing process, as usual.

The Falcon 9 second stage released Hotbird 13F into its geostationary transfer orbit after a short coast phase and one-minute duration second burn of the engine. The satellite’s xenon engines will do the rest of the work to deliver it into geostationary orbit.

Hotbird 13G will join 13F in orbit as early as this November.

SpaceX continued a busy week with the return of the four astronauts of the Crew 4 mission from the ISS to Earth on October 15. Breaking from routine, Crew Dragon Freedom undocked the same day as its deorbit and returned to Earth only five hours after undocking.

Crew Dragon undocked just after noon Eastern on the 15th. Just before 16:00 Eastern, the deorbit burn was completed.

Unlike Soyuz, Crew Dragon does its deorbit burn without the service section attached, leaving it to return uncontrolled after several months of atmospheric drag. The reason this is done is to avoid any problems that could result from separating the trunk after the burn, such as interfering with the heat shield during re-entry.

Freedom splashed down off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida, at 16:55 Eastern, within sight of the waiting recovery vessels. The ship lifted it out of the water and each crewmember was brought out in turn.

With the landing, NASA’s Kjell Lindgren has now spent 311 days in space on two missions, and ESA’s Samantha Cristoforetti 369 days, making her number two on the list of most time spent in space by a woman. Jessica Watkins completed her first trip into space and has already set a record for the most time in space by an African-American woman at 170 days. Rounding out the crew was Bob Hines, who was on his first mission in space.

Finally, Russia also launched two rockets last week, one carrying a commercial payload and the other a military payload.

Before we go, I just want to draw your attention to one final thing. There is a new space race in town. SpaceX has announced plans to try and launch their StarShip into orbit in early November, potentially beating NASA’s SLS to orbit. Mind you, SLS was supposed to launch in 2016, so a lot of things have beat SLS into orbit.

We’ll bring you more updates as the launch approaches. For now…

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org.

This show is brought to you thanks to the donations of myriad people. Right now, we’re doing our fall fundraiser. Our goal is to raise $50,000 by Dec 1. The vast majority of you out there don’t donate, and we get it. Times are hard. But, if you are one of the folks doing ok right now, please help our team do ok going into the new year and donate at CosmoQuest.org.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Annie Wilson, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, and Gordon Dewis

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.