On this week’s Rocket Roundup, a sounding rocket launches with student payloads, the Russian Space Force launches a classified satellite, and finally, a routine ISS resupply mission. Plus, this week in rocket history, we look back at STS-71 and the first Shuttle-Mir docking.

Podcast

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

First up, on June 25 at 13:32 UTC, a two-stage, Terrier-Improved Orion suborbital sounding rocket launched one hundred student payloads from the Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia.

Sponsored by the Colorado and Virginia Space Grant Consortiums, the launch was part of the annual RockSat-C program which is currently in its thirteenth year. According to a NASA press release on the program: [p]articipants in RockOn! receive instruction on the basics required to develop a scientific payload for flight on a suborbital rocket. After learning the basics in RockOn!, students may then participate in RockSat-C, where during the school year they design and build a more complicated experiment for rocket flight.”

Because of the impacts of COVID-19, the usual in-person learning workshop at Wallops had to be done virtually after the 2020 edition was postponed. Chris Kohler, director of the Colorado Space Grant Consortium, stated that: One big advantage of the virtual process is that participants worked in small teams or individually at their own pace.

This led to an increase in payloads from previous years, from 28 payloads in both 2018 and 2019 to 66 this year. The students built so many payloads, covering everything from acceleration, humidity, pressure, and temperature to radiation counts, that they could only fit 32 in the space available. The 34 remaining payloads will be launched into the stratosphere this fall on a large balloon. When that happens, we’ll tell you about it here on Daily Space.

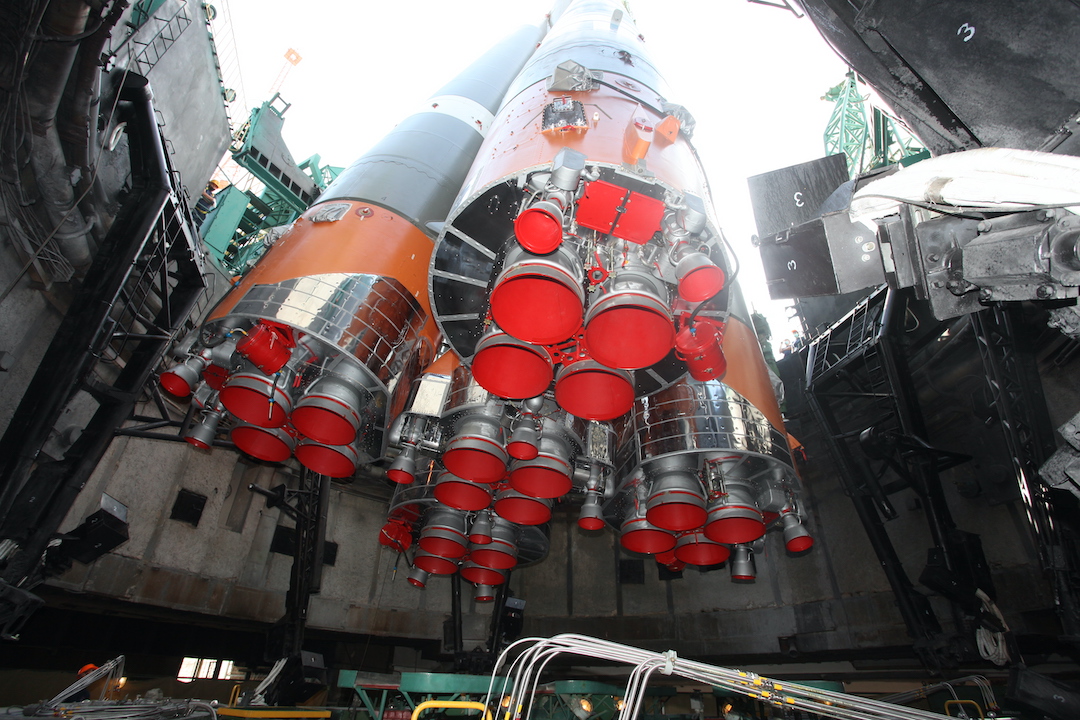

Just a few hours later, on June 25 at 19:50 UTC, the Russian Space Forces launched a Soyuz 2.1b with the Pion-NKS satellite into orbit from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northern Russia.

Because of its military nature, nothing was said officially about the satellite by Russian sources except that it was “a new generation spacecraft in the interests of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation.” Once in orbit, it was given the designation Kosmos 2550. Kosmos is the standard designation given to all Russian (and previously, Soviet) military satellites to conceal their true purpose. In total, eighty soldiers and fifty vehicles were involved in the launch campaign.

Pion-NKS is the first in the next generation of naval reconnaissance satellites for Russia, combining the missions of two previous series of satellites into one spacecraft. The two missions are signals intelligence and radar. As such, Pion-NKS has the capability to identify where ships are in the ocean with radar and what transmissions they are sending or receiving with the signals intelligence equipment.

Our last launch of the week took place on June 29 at 23:27 UTC, when a Russian Soyuz 2.1a launched the Progress MS-17 cargo resupply from Baikonur. It will dock at the International Space Station on July 2 at 01:02 UTC.

Progress MS-17 will deliver three tons of food, repair tools, scientific experiments, and propellant. One of the more interesting payloads is the food, some of which is freshly made by the ISS Crew Nutrition Department of the Institute of Medical and Biological Problems (IMBP) of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Each of the crew members gets to choose what food they like. The options included things like goulash, borscht, and mixed nuts.

We’ve put a full list of the food that was delivered on our website, DailySpace.org.

Progress MS-17 also carried many science experiments. One experiment will investigate countermeasures for bone fractures in zero-g. This experiment is important because bones lose density in zero-g as they are no longer subject to the mechanical stress of gravity. When astronauts return to Earth, they are at increased risk of breaking bones because of that lower density. An effective way to prevent bone loss in zero-g is to induce mechanical stress on the body through exercise, such as by running on a treadmill.

The Biorisk experiment will investigate the impact of spaceflight on blood plasma compounds. And one final experiment will investigate the production of medication in zero-g that can modify the immune system.

Progress also delivered 470 kilograms of propellant for the station’s orbit-raising engines, 420 liters of drinking water, forty kilograms of bottled air, and 1,509 kilograms of other equipment.

Asteroid Day

Today is Asteroid Day, and it seemed fitting to feature current and future asteroid missions.

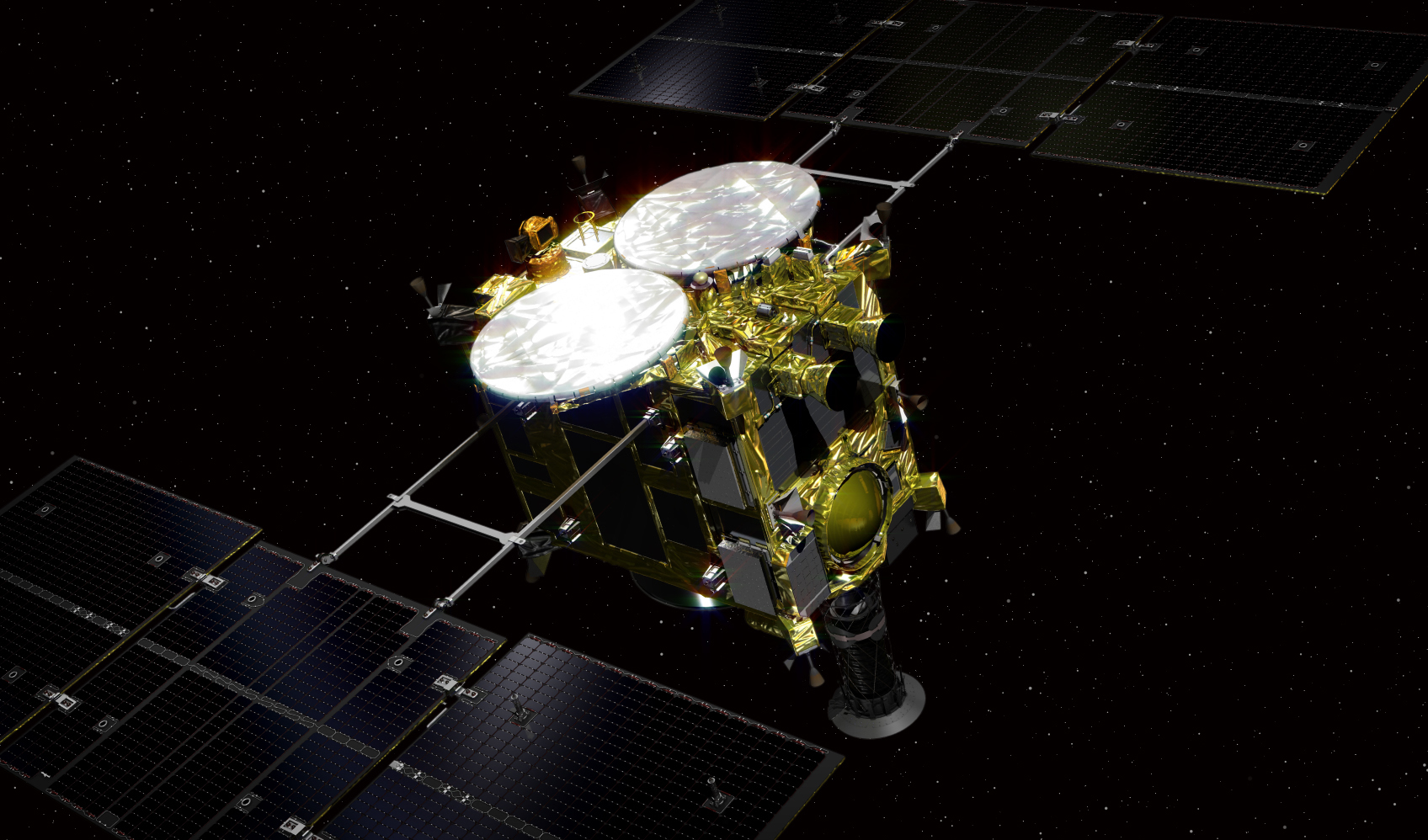

Launched in 2014, Hayabusa2 arrived at the asteroid Ryugu in 2018. Once there, the spacecraft effectively shot a bullet, called an impactor, to expose undisturbed material just below the surface. Hayabusa2 collected a sample of this unweathered material to bring back to Earth. Because the sample was not subject to weathering from radiation and impacts with other rocks in space, it will give scientists a better idea of the asteroid’s properties.

Hayabusa2 successfully returned those samples back to Earth in December 2020. That doesn’t mean its mission is over; the spacecraft will continue on and visit asteroid 2001 AV43 in 2029 and asteroid 1998 KY26 in 2031. These two asteroids are what are known as “fast rotators” because the time they take to spin on their axis is only ten minutes. Humanity has not visited an object like this before so it will provide a useful contrast to the rubble pile asteroids Ryugu and Bennu.

After arriving at the asteroid Bennu in December 2018, OSIRIS-REx spent several months imaging the surface in detail to find a suitable collection site. That turned out to be a challenge; the science team was expecting to find a smooth surface clear of major hazards. Instead, the images revealed huge boulders jutting out from an extremely rocky surface with very few smooth areas.

With the help of over 3,500 volunteer citizen-scientists in CosmoQuest’s Bennu Mapper project who painstakingly marked over fourteen million rocks, boulders, and craters on thousands of images from OSIRIS-REx, spending about 45 minutes on each image, four sites were identified. Using this information to identify possible sample sites, OSIRIS-REx collected a sample in October 2020 from the sample site called Nightingale, located inside a crater near the asteroid’s north pole. The spacecraft began its return to Earth in mid-May 2021, and it will arrive in September 2023. After it delivers its sample to Earth it, too, will continue on to an extended mission.

Launching later this year is humanity’s revenge for an asteroid taking out the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous Period. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, is pretty much what it sounds like: a test to see if humanity can redirect not one but two asteroids.

The double asteroid target for this NASA mission is the binary asteroid system Didymos. A binary system is one where two objects orbit each other as they orbit the Sun. In this case, the system is the Didymos and its smaller companion Dimorphos [Ed. note: DIDYMOON!].

Before I continue, I want to point out that their orbit doesn’t cross Earth’s orbit, and there is absolutely no threat of either Didymos or Dimorphos hitting us. I repeat: they will not impact Earth.

With that said, the fact that it will never collide with our planet makes it the perfect test subject for this mission. DART will impact Didymos, and because of that not crossing paths with Earth bit, scientists and engineers will be able to safely see if humanity can change the orbit of a potentially hazardous asteroid.

And its companion Dimorphos? It’ll be fine. The kinetic energy resulting from the test isn’t high enough to disturb its orbit in a way that would result in a future collision.

This Week in Rocket History

This week in rocket history, we’re going to cover the launch of STS-71, the first spacecraft to dock to another nation’s space station.

When Atlantis launched on June 27, 1995, STS-71 became the one-hundredth crewed launch from Kennedy Space Center. Onboard were five American astronauts and two Russian cosmonauts.

This was the first time Russians went to space on an American spacecraft. Prior to that, the last time Russians and Americans worked together directly was on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Program twenty years earlier at the height of the Cold War.

Together, they would continue to achieve several “space firsts” for both nations.

After two days of catching up to Mir, STS-71 became the first American spacecraft to dock to another country’s space station. Shuttle Atlantis came up directly below Mir to dock on the Kristall module. This was the only module the Shuttle could dock to as all others had the standard Soyuz port, which was not compatible with the Shuttle. To make room for the shuttle, the Kristall module was temporarily moved to the forward port of the Mir core.

Eight hundred meters away from the docking port, commander Robert Gibson took over manual controls and brought the Shuttle in for a soft docking. His docking was nearly perfect; the alignment was only off by 2.5 centimeters (one inch). When docked, Atlantis and Mir formed the largest spacecraft ever at the time, over 225 metric tonnes. For comparison, the International Space Station is now over 400 metric tonnes.

After docking and opening the airlocks, the commanders of the two spacecraft, Gibson and Vladimir Dezhurov did a ceremonial handshake, just like their counterparts Thomas Stafford and Alexi Leonov did twenty years earlier.

Atlantis spent five days conducting human biomedical experiments with the combined American and Russian crews. These experiments covered seven different disciplines:

- cardiovascular and pulmonary functions;

- human metabolism;

- neuroscience;

- hygiene, sanitation, and radiation;

- behavioral performance and biology;

- fundamental biology; and

- microgravity research.

Most of these experiments were conducted from the Spacehab module in Atlantis’ payload bay.

Atlantis brought back biological samples including blood, urine, and feces from these different experiments, as well as a broken computer from Mir so it could be fixed on the ground. The crew transferred 450 kilograms of water as well as spacewalking tools needed for repairs to the station.

Before undocking, the Shuttle exchanged crews, leaving behind Nikolai Budarin and Anatoly Solovyevso the Mir Expedition 18 crew could go back to Earth. This resulted in seven crew members going up and eight coming back down, which is the largest crew on any spacecraft for launch or landing. Budarin and Solovyev became Mir Expedition 19 and remained on board until September 1995, when they would depart in the Soyuz that had launched Expedition 18.

Both craft undocked from Mir, temporarily leaving the station empty. This was so that the remaining crew could take photos of the Shuttle undocking. After the photoshoot, the spacecraft went their separate ways: Soyuz re-docking with Mir while Atlantis headed back to Earth. Ten days after launch, the eight-person crew landed safely back at the Kennedy Space Center on July 7, 1995.

The Shuttle-Mir program gave NASA a lot of experience in long-duration missions, space station operations, and working with the Russians. Hardware from the program, specifically the APAS-95 docking port on the Shuttle, would later be used on the International Space Station.

Statistics

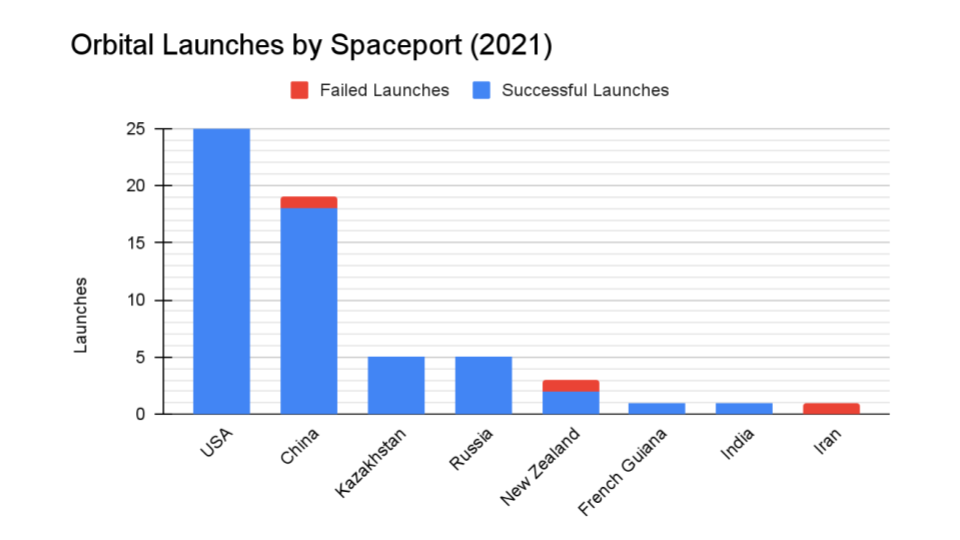

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 7: 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz, 1 on the Shenzhou, and 1 on Tianhe

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 60, including 3 failures

Total satellites from launches: 1158

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 25

China: 19

Kazakhstan: 5

Russia: 5

New Zealand: 3

French Guinea: 1

India: 1

Iran: 1

Random Space Fact

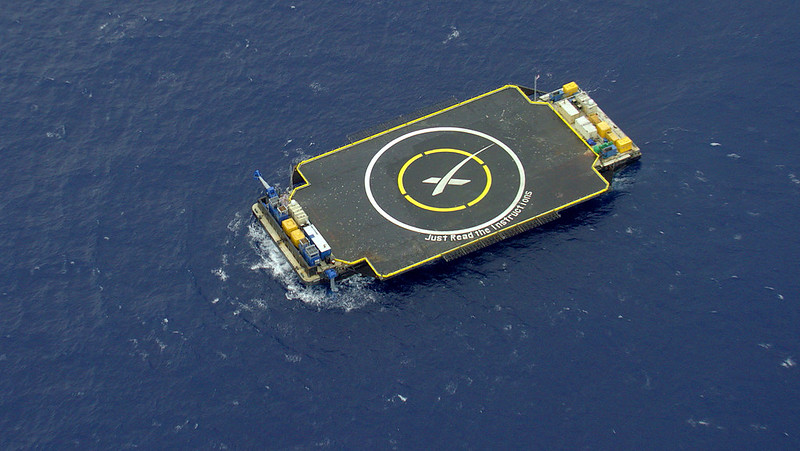

Your random space fact for this week is that all four of the SpaceX barges take their names from the Culture novels by Iain M. Banks. Marmac 303 and Marmac 304, Of Course I Still Love You and Just Read The Instructions, take their names from the book The Player Of Games. The third droneship in the fleet, Marmac 302, (really fourth, as both Marmac 300 and Marmac 303 were named Just Read The Instructions) will be called A Shortfall of Gravitas, a reference to Experiencing A Significant Gravitas Shortfall from the book Look To Windward.

This has been the Daily Space.

Learn More

Suborbital Rocket Launches With Student-Made Payloads

Russia Launches Classified Satellite

- Russian Defense Ministry press release (Russian)

- Roscosmos press release (Russian)

- The status of Russia’s signals intelligence satellites (The Space Review)

- Launch video

Routine ISS Resupply Launch Brings Food, Experiments

- Roscosmos press release (Russian)

- Roscosmos pre-launch press release

- Progress will deliver Russian food to American and Japanese astronauts on the ISS (TASS)

- What happens to bones in space? (Canadian Space Agency)

- Launch video

Asteroid Day: Robotic missions abound!

- Launch of “Hayabusa2” by H-IIA Launch Vehicle No. 26 (JAXA)

- Arrival at Ryugu! (JAXA)

- Shooting bullets into Ryugu! (JAXA)

- Images of the capsule after landing back on Earth (JAXA)

- Extended mission after Hayabusa2 returns to Earth (JAXA)

- Asteroid Operations (OSIRIS-REx)

- CosmoQuest Citizen Scientists Help Map Asteroid Bennu (PSI)

- NASA’s OSIRIS-REx Spacecraft Heads for Earth with Asteroid Sample (OSIRIS-REx)

- DART Mission Overview (JHUAPL)

This Week in Rocket History: STS-71

- Mission Archives: STS-71 (NASA)

- Shuttle-Mir Background: Lessons Learned (NASA via archive.org)

- BOOK: The Twenty-first Century in Space by Ben Evans

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.