Scientists examined over 80,000 images from large telescopes and their sensitive instruments and found over 70 free-floating planets with the possibility for even more. Plus, a red giant supernova, new images of the Flame Nebula, and a review of Netflix’s “Don’t Look Up”.

Podcast

Show Notes

Starlink L34 adds 49 satellites

- Starlink Mission (SpaceX via archive.today)

- Launch video

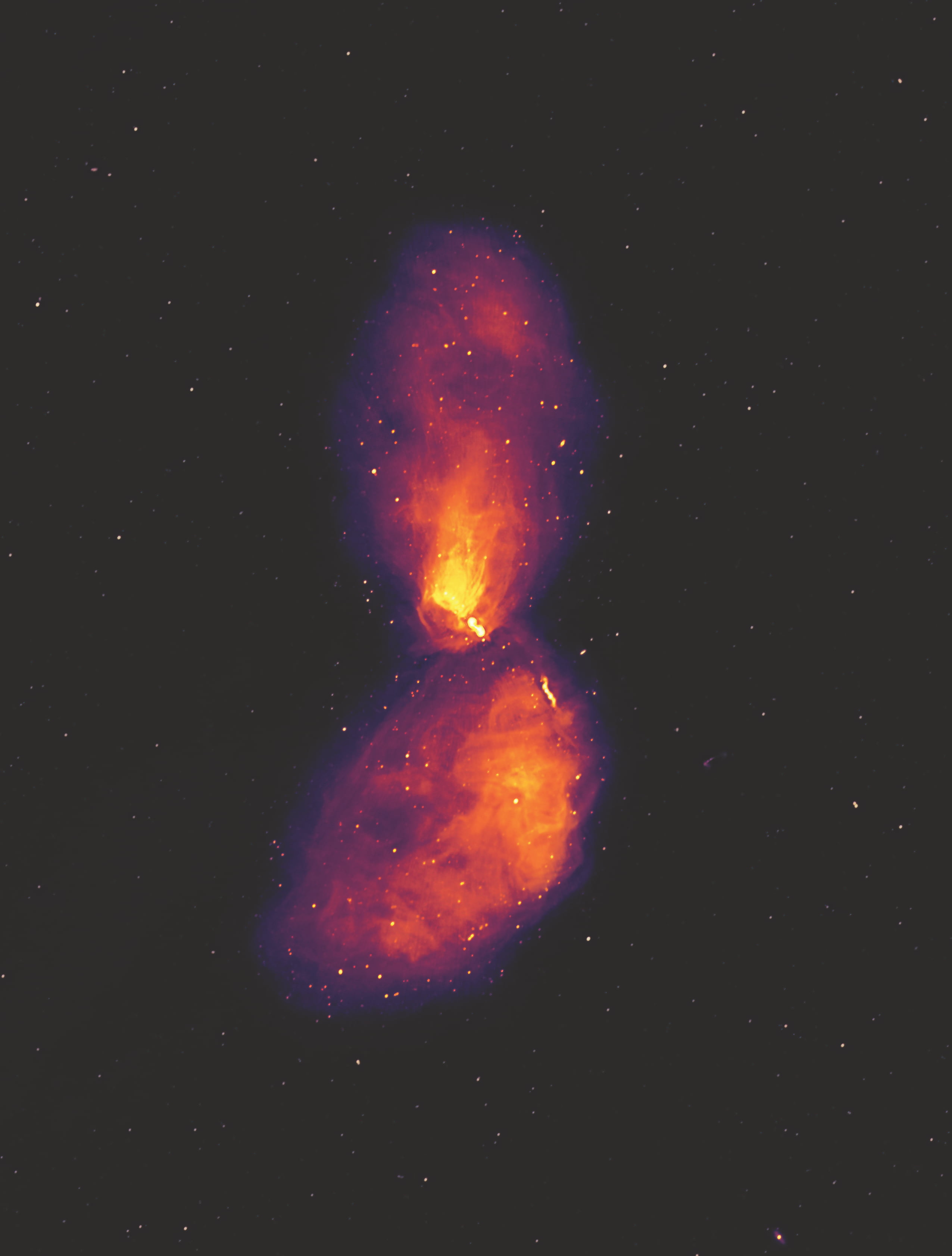

Stunning new view of galaxy’s jets

- ICRAR press release

- “Multi-scale feedback and feeding in the closest radio galaxy Centaurus A,” B. McKinley et al., 2021 December 22, Nature

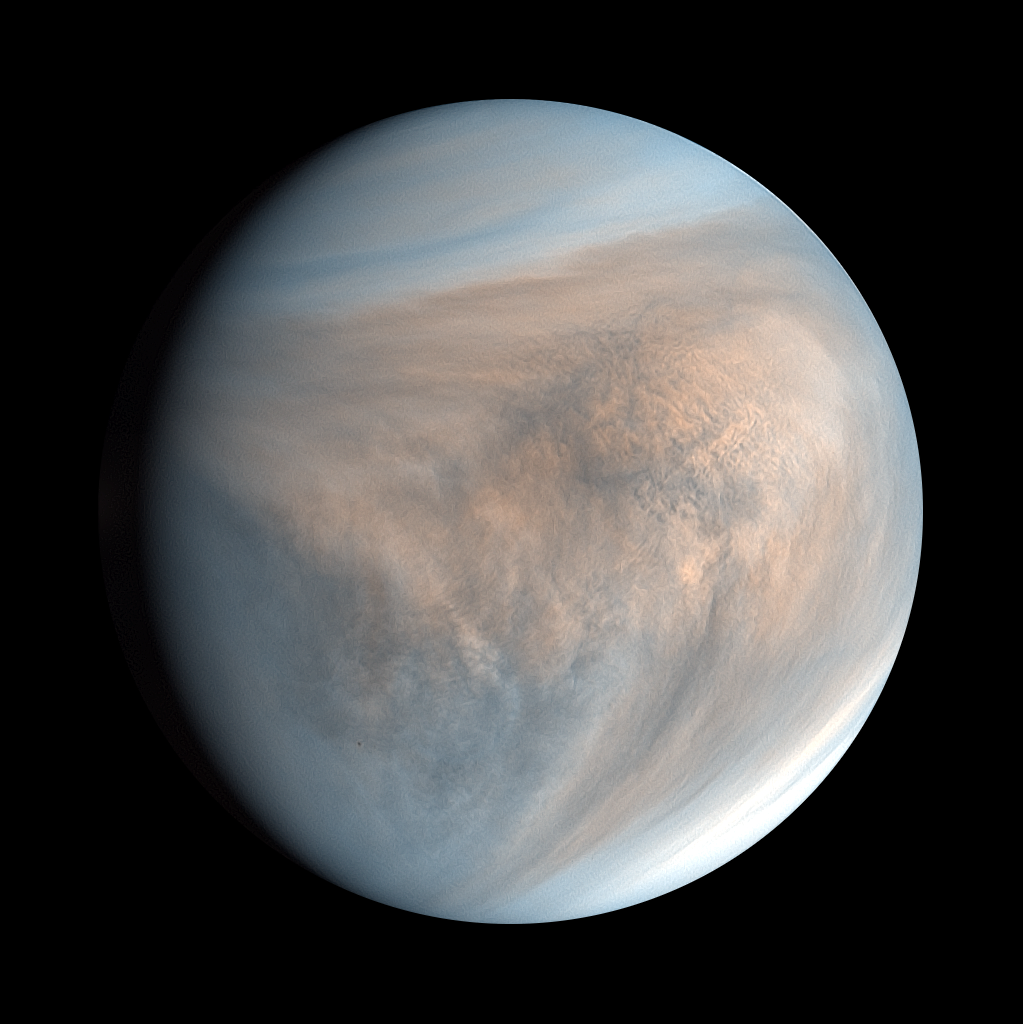

Debate on Venus life continues

- University of Wisconsin–Madison press release

- “Venus, an Astrobiology Target,” Sanjay S. Limaye et al., 2021 May 7, Astrobiology

- “Introducing the Venus Collection—Papers from the First Workshop on Habitability of the Cloud Layer,” Sanjay S. Limaye et al., 2021 September 28, Astrobiology

Free-floating planets abound in Milky Way

- Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes press release

- NOIRLab press release

- Subaru Telescope press release

- “A rich population of free-floating planets in the Upper Scorpius young stellar association,” Núria Miret-Roig et al., 2021 December 22, Nature Astronomy

Red giant caught exploding

- Keck Observatory press release

- “Final Moments. I. Precursor Emission, Envelope Inflation, and Enhanced Mass Loss Preceding the Luminous Type II Supernova 2020tlf,” W. V. Jacobson-Galán et al., 2022 January 6, The Astrophysical Journal

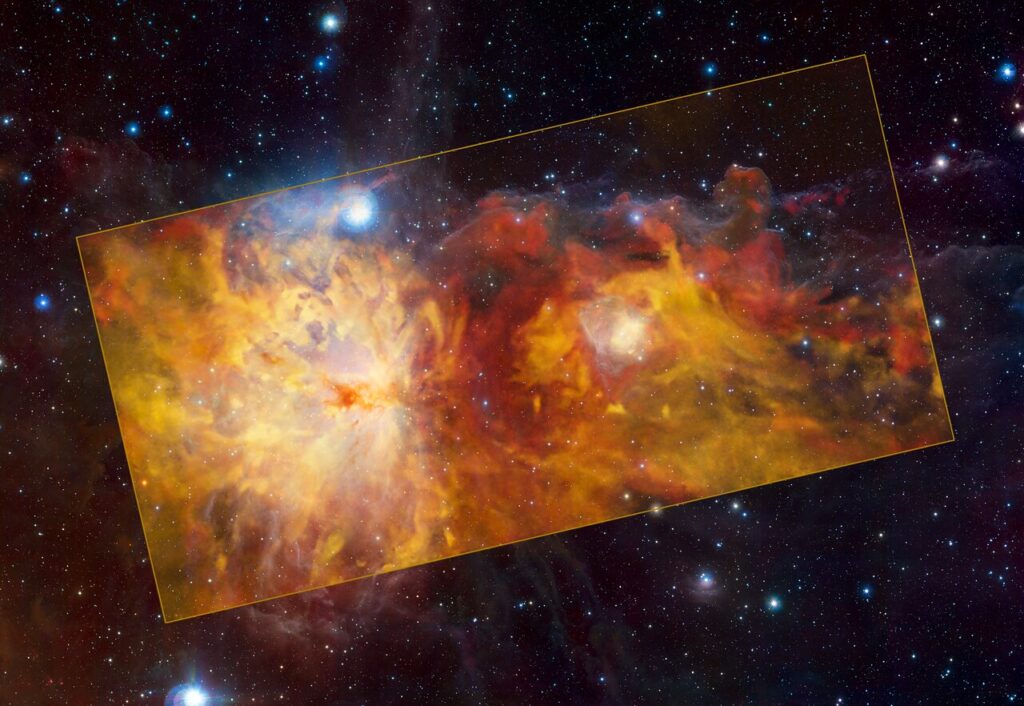

Flame Nebula is lit in new radio image

- ESO photo release

- “The APEX Large CO Heterodyne Orion Legacy Survey (ALCOHOLS). I. Survey overview,” Thomas Stanke et al., to be published in Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint on arxiv.org)

Transcript

Hello and welcome to the Daily Space. I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay.

And I am your host Beth Johnson.

And we are here to put science in your brain.

We’re going to start things off with the latest rocket launch with Erik Madaus.

On January 6 at 21:49 UTC, the Starlink 34 mission launched atop Falcon 9 booster 1062 from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

This was a flight that showed just how well SpaceX is at reusing its rocket hardware. This was the fourth flight for the first stage Booster 1062, which successfully landed on the droneship A Shortfall of Gravitas. Both fairings were also reused, with one half on their fifth flight and the other on their fourth.

All 49 satellites were successfully deployed into orbit sixteen minutes after launch following one burn of the upper stage.

This was the first orbital launch of 2022, and it targeted the 53.2-degree inclination shell of the Starlink constellation, taking the unusual but steadily becoming the norm southern launch track down the Florida coast. This trajectory required the second stage to bend the trajectory further west after the first stage separation. The stated reason for this, explained on the webcast, was the weather conditions in the south were better for recovery of the booster and fairings in the winter months, which is critical for the high flight rate that Starlink requires. However, this incurs a loss of payload capacity so the rocket carried only 49 satellites instead of the 52 or 53 which have gone to the 53.2-degree inclination previously.

The Starlink satellites are ones that have our team feeling all the mixed emotions. Seeing SpaceX perfect its reusable rockets using their own hardware is awesome. Seeing people in low-infrastructure regions get infrastructure is awesome. We just wish Starlinks didn’t make such a mess of folks attempting to image the sky.

If you want to see videos of the SpaceX launch and landing, check out our website, DailySpace.org.

Luckily, the Starlink satellites don’t wreak havoc on all images, and so far, as long as they turn off their transmitters when they are supposed to, these new satellites are leaving alone the radio sky, and the new Murchison Widefield Array in Western Australia is using its more than 4,000 antennae to capture stunning images of light we can’t see with our eyes. In a newly released image of the galaxy Centaurus A, stunning jets are seen stretching more than a million miles from the galaxy’s energetic heart.

Most large galaxies contain supermassive black holes in their center, and when material spirals in toward the black hole, it can get heated and generate a powerful magnetic field. That magnetic field can, in turn, fire particles out of the galaxy like a rail gun, and those particles, over years and millennia, build up and even interact with their surroundings.

If we could see in the radio, our view of the sky would be very different, and this particular galaxy would stand out in the night as a smudge sixteen times longer than the Moon is wide!

It would look like a smudge – and has looked like a smudge with prior telescopes – because it is so bright that getting a good image was hard. According to lead author Benjamin McKinley: Previous radio observations could not handle the extreme brightness of the jets and details of the larger area surrounding the galaxy were distorted, but our new image overcomes these limitations.

This work appears in Nature Astronomy.

The Murchison Widefield Array is a proof of concept system developed to trial new technologies that will be used in the future Square Kilometer Array. What we see here is only a taste of the amazing science that is to come.

Science is a process. And sometimes it is a process that seems to zig and zag a lot.

The planet Venus has always been a place folks look to and want to see the potential for life. Prior to visiting it with spacecraft, folks imagined it was a tropical world. Then, we learned it’s 900 degrees Fahrenheit and rains acid. So, not so much of a paradise.

But, researchers keep looking for ways for Venus to be good for life, and a new paper in the journal Astrobiology distills out the discussions of more than fifty scientists who met in Moscow in 2019 to discuss Venus’s potential for life.

The paper reminds readers that Venus spent three billion years with a more Earth-like ocean environment that could have evolved microorganisms just like Earth. Further, it repeats the idea put forward since the 1960s by folks, including Carl Sagan, that life could exist in the clouds, and some observations – including the repeated imaging of dark patches – are consistent with life; they just aren’t proof.

We bring this paper up just as a reminder that there could be life on Venus, and that is kind of awesome. This isn’t two crazies off in the corner saying “Venus has aliens”; this is a global community saying what we see is consistent with the possibility of life, but we can’t prove it. And even if it doesn’t have it today, it may have had it in the past.

And sometimes, it is this amazing “life may have found a way” story that we need to have in our day.

Of course, if you like things less hopeful, there is also a new paper on more than seventy worlds without suns.

This story was actually released right as we went on hiatus for the holidays, but I have been wanting to write about it ever since. In a paper published in Nature and led by Núria Miret-Roig, researchers detail the discovery of at least seventy free-floating planets in a region of the Milky Way known as the Upper Scorpius OB stellar association. And there could be as many as 170 planets hidden within the twenty years of observations the team analyzed.

Free-floating planets are those planets that are not currently orbiting a star. We used to call them rogue planets, as they had gone rogue from their stellar system of origin, but since we don’t know how true that particular description is, the term was changed to ‘free-floating’. Of course, since these planets are not orbiting a star, they are also not reflecting or blocking a star’s light, nor are they gravitationally influencing a star’s orbit. And dark, cold objects are difficult to detect.

In the past, detecting free-floating planets involved microlensing, using the chance alignment of an exoplanet and a background star and detecting the gravitational distortion that bends the light around the planet. This project, however, sought out free-floating planets that were actually still hot enough to produce light in visible and infrared light that was detectable by very sensitive cameras on large telescopes, including the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, and the Subaru Telescope. The Dark Energy Camera was one of the instruments involved. Per the press release: Miret-Roig’s team used the 80,000 observations to measure the light of all the members of the association across a wide range of optical and near-infrared wavelengths and combined them with measurements of how they appear to move across the sky.

Miret-Roig goes on to explain: We measured the tiny motions, the colors, and luminosities of tens of millions of sources in a large area of the sky. These measurements allowed us to securely identify the faintest objects in this region.

As I mentioned earlier, why there are free-floating planets is a matter of debate. While being ejected from their parent system is one possibility to explain the existence of these elusive objects, another possibility is that they could have formed from the collapse of a very small gas cloud, one too small to make a star but big enough to create a large gas giant. This study and future discoveries will help us understand just how these exoplanets came to be and why they are alone (ish) in space.

Also, Miret-Roig notes: The free-floating Jupiter-mass planets are the most difficult to eject, meaning that there might even be more free-floating Earth-mass planets wandering the galaxy.

And now I will join Pamela in greatly anticipating first light for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which could detect even more of these free-floating planetary mysteries.

While these free-floating planets were somewhat cool and dark and hard to detect, we still have a lot of bright objects to look at, including stars going supernova and beautiful nebulae.

Much to everyone’s disappointment, the 2019 dimming of the red giant star Betelgeuse did not lead to this familiar star going supernova. While we missed out on a show we could all watch with our eyes, another team, using the Keck Observatory massive scopes, was able to watch a red giant star transition – as Betelguese will one day transition – from a blobby red giant to a spectacular type II supernova. This is the celestial version of a glow-up.

In a new paper in the Astrophysical Journal, researchers led by W.V. Jacob-Galan published their description of this event, which is designated SN 2020tlf.

In the summer of 2020, the Pan-STARR Survey noted a massive red giant emitting a huge amount of light and while monitoring it, caught the detonation in Fall 2020. They then hopped on the scene with the KeckObservatory’s Low-Resolution Imaging Spectrograph.

The detailed observations will provide new insights into the detailed evolution of a star in its final moments and offer a hint at how we can gather more of these observations. According to Jacobson-Galan: It’s like watching a ticking time bomb. We’ve never confirmed such violent activity in a dying red supergiant star where we see it produce such a luminous emission, then collapse and combust, until now.

Put another way, we need to watch for Betelguese to get brighter, not dimmer when it is about to explode.

Jacobson-Galan goes on to add: I am most excited by all of the new ‘unknowns’ that have been unlocked by this discovery. Detecting more events like SN 2020tlf will dramatically impact how we define the final months of stellar evolution, uniting observers and theorists in the quest to solve the mystery of how massive stars spend the final moments of their lives.

Stars often get a bad rep in astronomy because they go through most of their lives doing nothing more interesting than maybe pulsating or flaring. But the drama they create during their birth and death is definitely something worth watching.

And the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment, or APEX, has been watching an amazing star-forming region. Called the Flame Nebula, this cloud of dust, gas, and young stars is a favorite for many amateur astronomers and is part of the greater Orion Star Forming region. APEX sees the sky in millimeter and sub-millimeter light – colors that can be called either radio or long infrared. In these colors, the nebula’s cold material shines like fire, as vibrant details in the dust patterns are revealed.

While ESO released this image as a holiday gift. A paper led by Thomas Stanke on this work has been accepted to Astronomy & Astrophysics. A preprint discusses how this image reveals the role of carbon monoxide in this cloud.

This image is basically a thousand words that explain why we need to always look up.

Review

Speaking of looking up, the talk of the scicomm community over the month of December was a new movie from Netflix called Don’t Look Up. Starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence, this movie was originally released in theaters for those brave enough to actually go to a theater. It was added to Netflix on December 24. I finally watched it last night, and I can admit that I was hesitant to watch it. I managed to avoid spoilers, and I’ll try to do the same for you all, but I couldn’t help but see the reactions of friends and colleagues.

And as Pamela said to me this morning, a lot of it came down to “I’m in this picture and I don’t like it”.

Let’s start at the beginning. We open on an observatory in Hawai’i. It’s the Subaru Telescope, in fact, and one of the images that flash on the screen is actually an object my friend Michael (a fellow undergraduate alum) discovered. According to our astrophysics professor and research adviser, their poster hangs in the hallway at the observatory, and the camera crew must have grabbed it from there. Pretty neat, and I’m very excited for him and our professor.

Jennifer Lawrence is doing the graduate student thing, getting the telescope set up for observations, checking out computer data, etc. Pamela could probably speak more to that process than me as she has actually spent nights at a telescope. The telescope’s adaptive optics laser guide turns on, and we get a full shot of the domes up on Mauna Kea. I admit to a few feelings of envy toward my friend Michael again as he actually got to go there and do his follow-up observations on his galaxy discovery.

But I digress.

Jennifer’s character, Kate Dibiasky, has discovered a comet. Her adviser is Dr. Randall Mindy, played by DiCaprio, and he joins her along with the rest of her cohort who is also there working on their research. They’re from Michigan State, a point that is necessary for later. Dr. Mindy starts asking the team questions about the object, and they begin running orbital calculations to get all the ephemeris numbers for this newly found comet, and something is clearly wrong. Dr. Mindy sends the other team members away and keeps Kate with him. It turns out that Comet Dibiasky is very big and headed directly toward Earth, arriving in six months and fourteen days.

And this is where the movie simultaneously fascinates me and also goes a bit off the rails. You see, it’s a satire, examining how our society would react to devastating news like this, and aside from the NASA Planetary Defence coordinator, everyone else basically sucks. I started to feel like the film was a series of Onion headlines brought to life, and actually hit the “thanks, I hate it” point during the first scene in the Oval Office.

Meryl Streep plays the President, and she’s the worst cross between Donald Trump and Bill Clinton that you can imagine. All concerned with politics and her image, and her Chief of Staff is her son, annoyingly portrayed by Jonah Hill in his most Jonah Hill way. They don’t want to take the situation seriously as it won’t poll well. And they are incredibly condescending about the team being from Michigan State and want scientists from Ivy League schools to check the numbers. Gross.

So the scientists turn to the media.

And from there, everything goes further off the rails, with a terrible romance or two, some awful internet memes, and for whatever reason, Ariana Grande playing a pop star. I did manage to make it through the movie, but I essentially hated everyone except the NASA coordinator. Even J Law’s Kate got on my nerves, although I do respect her nihilism and angst, and Dr. Mindy loses the plot early on. This is not a warm, fuzzy movie. It’s a dark satire, and it feels over the top enough to stay satire while at the same time, reminding you that it’s really not that far off from reality.

There’s also a bonus terrible subplot about a tech company called BASH and its founder, who is a pale, socially awkward genius with hints of Steve Jobs but not nearly the charisma. That subplot turned me off from the film a lot, but I can see it was necessary to keep the satire going. Still, I really didn’t like that part.

Overall, if satire is your thing, if you like dark humor, and you don’t mind end-of-the-world scenarios, then Don’t Look Up is for you. The science is fine. In fact, Amy Mainzer of NEOWISE fame was the astronomy consultant on the movie. That’s all well and good, but I still found the movie a little too cringe for my tastes. I also feel like it could have ended five minutes earlier, and the stinger after the credits was wholly unnecessary. I know Ally disagrees a bit, and we’ll have her review in our bonus content on Patreon.

Honestly, though, please please please look up. It’s pretty amazing up there.

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.