An analysis of the most recent sample taken from the Moon and returned by the Chang’e-5 mission shows that the basaltic rock is about two billion years old. This age implies a previously unknown heat source in the region. Plus, how plants and animals record climate change and this week’s What’s Up.

Podcast

Show Notes

BepiColombo images Mercury during flyby

- ESA press release

- BepiColombo: Europe’s mission to Mercury returns first pictures (BBC)

Binary system caught forming by ALMA

- NAOJ press release

- “Misaligned Circumstellar Disks and Orbital Motion of the Young Binary XZ Tau,” Takanori Ichikawa et al., 2021 September 23, The Astrophysical Journal

Active Galaxy dresses up as Eye

- ESA press release

- Hubble telescope spots celestial ‘eye,’ a galaxy with an incredibly active core (Space.com)

Nobel Prize in Physics given for Complex System Research

- The Nobel Prize press release

- Physics Nobel rewards work on climate change, other forces (AP)

China samples find young-ish volcanic rocks on Moon

- AAAS press release

- Curtin University press release

- WUSL press release

- “Age and composition of young basalts on the Moon, measured from samples returned by Chang’e-5,” Xiaochao Che et al., 2021 October 7, Science

Mussels measure Alpine snowpack

- Freshwater Mussel Shells May Retain Record of Alpine Snowpack (Eos)

- “Daily and annual shell growth in a long-lived freshwater bivalve as a proxy for winter snowpack,” Tsuyoshi Watanabe et al., 2021 May 1, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology

Cormorants collect coastal ocean data

Misplaced mangroves reveal past ocean heights

- UCSD press release

- “Relict inland mangrove ecosystem reveals Last Interglacial sea levels,” Octavio Aburto-Oropeza et al., 2021 October 12, PNAS

What’s Up: Orionid meteor shower peaks late October 2021

Transcript

Hello and welcome to the Daily Space. I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay.

And I am your host Beth Johnson.

And we are here to put science in your brain.

And sometimes science starts with really pretty images.

The BepiColombo mission is taking the slow, slow path to Mercury, and that means performing flybys as it slowly lowers its orbit around the Sun. Twice already this little mission has flown past Venus, and on October 1, it made its first of six flybys of Mercury. BepiColombo actually got closer to Mercury than the ISS is to Earth, zipping past at an altitude of 200 kilometers or 125 miles. BepiColombo is a joint mission of ESA and JAXA and once settled into orbit around Mercury, the current spacecraft will, like Voltron, come apart into multiple spacecraft that each carries on their own missions. In this case, the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MIO).

BepiColombo will execute its next flyby in June 2022 and will finally enter orbit in December 2025. This is a mission that teaches us that space exploration is all about waiting.

In more beautiful science news, we bring you an artist’s illustration of the XZ Tau system. The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope system took a multi-year series of scientifically stunning but aesthetically ugly images of this system that show these two stars are orbiting one another in a volume small enough to easily fit within the orbit of Neptune.

This is the first time we’ve been able to measure the 3D structure and motions of a forming binary system, and what’s more, these weren’t targeted observations. No one said, “Let’s point ALMA at XZ Tau every few years.” These observations were taken as part of regular surveys, and these results come from researchers going through the archival data. This work appears in The Astrophysical Journal and was led by Takanori Ichikawa who explains: This is a beautiful example of utilizing the rich ALMA archive. The archive paves the way for young researchers to start conducting cutting-edge research right away.

The second author on this paper was Muyu Kido, an undergraduate at Kagoshima University.

It is finally October, and this means everyone here at CosmoQuest is thinking about just two things: our Hangout-a-thon on October 23 and 24 and Halloween. I, for one, will be dressing up as a panda because Po. Halloween, honestly, is a state of mind, and many of us dress up on a regular basis for sci-fi cons and… Well, do really need a reason? This galaxy certainly didn’t.

Galaxy NGC 5278 is about 130 million light-years away, and in this new Hubble Space Telescope image, it looks strikingly like an eye. In this image, we’re only looking at the innermost structure of the galaxy, and within the outline of young blue stars and star formation is a dense region of activity. There are both clouds of star formation, and invisibly lurking in the center, is an active black hole that is chowing down on infalling gas, dust, and other material.

This image was released by ESA as essentially a pretty picture release. This is the scientist equivalent of someone running around going, “OMG, look at this awesome picture we took!” A close look at the byline for this image shows A. Riess, and we’re thinking that may refer to Nobel laureate Adam Riess, and we look forward to seeing what new science he is pulling from this data set and how it will help us measure our expanding universe.

Speaking of Nobel Prize winners, this is the week when many of the world’s top researchers, writers, and economists make sure they are awake with their phones at the ready at just before noon in Sweden, a time that is early morning for most here in North America.

On Tuesday, the Nobel Prize was given to researchers who sorted the physics behind climate change. According to the Associated Press: Syukuro Manabe, originally from Japan, and Klaus Hasselmann of Germany were cited for their work in developing forecast models of Earth’s climate and ‘reliably predicting global warming.’ The second half of the prize went to Giorgio Parisi of Italy for explaining disorder in physical systems, ranging from those as small as the insides of atoms to the planet-sized.”

So far, all of this year’s Nobel prizes in sciences have gone to men, and seven of those eight prizes went to white men. This highlights the role privilege plays in allowing people access to education, resources, and recognition of their achievements. We look forward to a day when all nations have equal access to the tools of research and all peoples of the world have an equal opportunity to advance our understanding of the world.

This next story is so fresh off the presses that we had to be careful tweeting about it before the show so that we didn’t break the embargo.

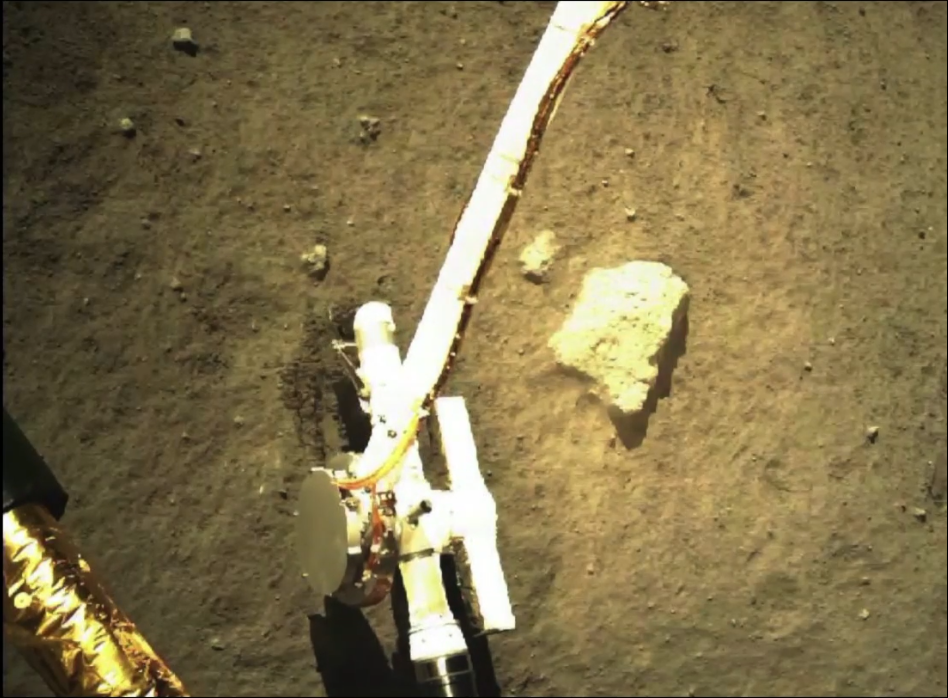

Last week, we talked about some early results from the analysis of lunar samples brought back by China’s Chang’e-5 mission which revealed that about 10% of those rocks were not from the landing site in Oceanus Procellarum. That landing site is basically known to be solidified lava near an ancient volcanic eruption. But while those so-called exotic rocks are interesting, today we’re going to talk about the ones that actually originated in the landing site instead.

In a new paper published in the journal Science, researchers report that the basaltic lava found in Oceanus Procellarum is only two billion years old. Yes, that’s billion with a ‘B’, and yes, the usage of “only” is correct here. We know the Moon is the same age as the Earth. We think we understand how it formed and how it ended up in Earth’s orbit, although the details keep being refined as we learn more. So while we can say with some certainty that Earth was hit by a Mars-sized body we call Theia, at least once, shearing off Earth’s materials and mixing together to solidify into the Moon and part of Earth, all of that still happened about four and half billion years ago.

The volcanic history of the Moon goes all the way back to 4.2 billion years ago, and previous data suggests that the bulk of the eruptions occurred between 3.8 and 3 billion years ago. The eruptions consisted mostly of basaltic lava flows from fissure vents, similar to what we have seen in Hawai’i, Iceland, and La Palma. The lava was incredibly primitive, without a lot of prior crystallization, so it flowed quickly and smoothly, resulting in the dark, flat mare or seas we see on the surface of the Moon today.

Two billion years ago is pretty close in time comparatively.

Now, these are not the first lunar rocks brought back from the Moon and analyzed. They are, however, the youngest ones brought back. And that leads to some interesting questions, such as what was the source that provided the heat to make the lava molten? Scientists have found no evidence of the high concentrations of radioactive elements necessary in the mantle to produce enough heat to keep rock in a magmatic state. This means we need an alternate heat source, and one possibility is tidal heating, similar to the mechanism that keeps Io volcanic.

Some mechanism kept lunar magmatism going longer than we originally thought. That’s pretty fascinating.

Additionally, these results give us a better constraint on just when craters on the Moon were created. The previous constraint was very wide at between one and three billion years ago, but if there was active volcanism two billion years ago, we can now calibrate the time of the craters based on these new lunar rock samples.

One other interesting mystery I want to mention is that there are some areas on the Moon imaged by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter that seem to indicate active volcanoes as recently as 50 million years ago. That’s what I would love to see a lander or rover sample next. Or a person. When is Artemis supposed to happen again?

Until then, we’ll keep bringing you the latest news from this newest set of lunar rock samples.

One of our sciences’ great frustration with the planet Earth is that our planet keeps hiding its past. Other worlds without weather preserve things on their surface for millennia, and while Mars’ polar ice caps do show seasonal changes and record changing weather, most of the surface of Mars is just hanging out, displaying features that formed millions to billions of years ago.

On Earth, that pretty much doesn’t happen. Each year, the weather wears away new surfaces, reveals new fossils, and plants hide, consume, and tear apart weaker rock. Trying to understand Earth’s past requires all sorts of creativity, and scientists are here to deliver.

A new paper in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, and led by Tsuyoshi Watanabe, shows how freshwater mussels in the Shiribetsu River in Japan can be used to track information on the mountain snowpack.

Melting snow is responsible for a significant portion of the river’s water, and when the temperatures are above 9˚C, river mussels will deposit layers in their shells on a daily basis. These mussels can live up to 200 years, and a collection of just twelve mussels allowed researchers to determine the past 67 years of annual snowfall data as reflected in water chemistry and flow. The shells also show variations on decadal scales that match with the known Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which is an oscillation in the temperature of the ocean. This work is new and indicates there is a new tool, or at least a new shell, in the scientific toolbox that we can use to measure the history of our world wherever mussels may live.

While humans remain the only Earth species to publish research papers, we are not alone in our pursuit of science, although many of our collaborators have no idea that they’re working as our research assistants.

Take the Cormorant Oceanography Project, for instance. This project is putting sensors on diving marine birds. These sensors allow researchers to study ocean salinity at a variety of depths and to measure surface currents, air-sea temperatures, and more. Once back at the surface, the sensors then radio home and upload data to researchers.

Since the birds travel into many hard-to-reach places while seeking food, they are able to get more data at a lower cost and with greater ease than your typical research student, research robot, or even research vessel. These are the kinds of information that are dearly needed by folks studying climate change, and it looks like atmospheric researchers are going to need to learn more and more about catching and tagging birds. This research is described in depth by Rachael Orben in Eos.

Animals aren’t the only lifeforms aiding climate researchers. Consider the mangrove. These tropical plants live along coastlines and thrive in environments with salty and brackish water. If you find a mangrove tree, it’s a pretty good bet that you are about to find an ocean shoreline.

Or, in at least one oddball case, a past shoreline.

Along the San Pedro Martir River, there is a red mangrove forest deep in the heart of Mexico. Far from any ocean, this particular forest has been a bit of a mystery until now. A collaboration of researchers from the University of California system and a variety of Mexican universities have studied the genetics of the trees, as well as other geologic and plant data, to piece together a story of a shoreline that did place these trees along a historic coast.

About 125,000 years ago, the oceans were significantly higher and these trees naturally spread along that now shrunken ocean’s coasts. At the time, the Tabasco lowlands of Mexico were covered in water by an ocean that was nine meters higher than today. As the coastline receded, these trees were able to survive thanks to the unique combination of minerals in the river.

This work is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was led by Octavio Aburto-Oropeza. Coauthor Felipe Zapata explains: This discovery is extraordinary. Not only are the red mangroves here with their origins printed in their DNA, but the whole coastal lagoon ecosystem of the last interglacial has found refuge here.

While sci-fi stories of lost tribes of ancient humans have proved to be just stories, it’s kind of amazing to know that, for plants, that kind of a story was real.

What’s Up

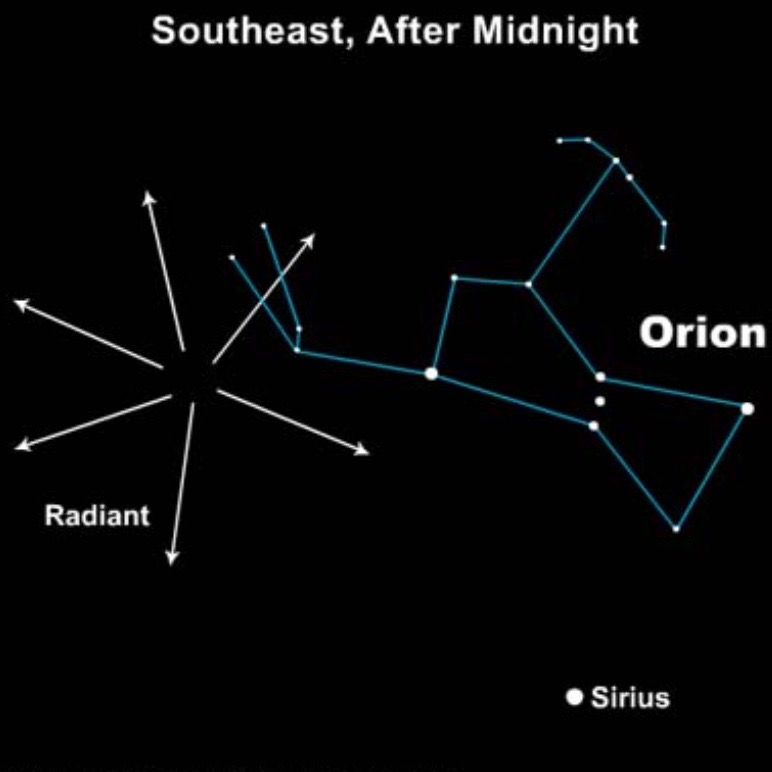

This week in What’s Up is another meteor shower, the Orionids. This meteor shower is highest in the sky at dawn, typical for meteor showers. It runs all the way through October and into early November, peaking in late October. Unfortunately, the full moon will wash out most of the meteors this year at their peak.

The Orionids typically produce a few dozen meteors an hour, unlike the more spectacular meteor showers of the year, and that is in ideal conditions at a dark site. Because of the full moon, you will see much fewer meteors than in other years. Still, it’s worth trying to look for them.

The apparent point in the sky where the meteors come from, the radiant, is in the constellation Orion, giving the shower its name. To find the radiant for the Orionids, first find the Orion Constellation near Sirius, the brightest star in the sky. Follow Sirius up and to the right a good distance until you see the red star Betelgeuse, which hasn’t exploded yet as of this recording. Further up are two more dim stars in the left hand of Orion. Near these two stars is the radiant for the Orionids.

We’re going to reiterate our advice from last week’s story on the Draconids. The best way to see a meteor shower is with the unaided eye, the widest field of view you can get. Be sure to let your eyes get well adjusted to the dark; we don’t recommend using a planetarium app on your phone because even the red light function will impact your dark adaption. You can download a map from a link at our website and print it out to bring with you in the field. Use a proper red light flashlight to see the map when you’re out. You can get one from Amazon using our affiliate link and support our show while you’re at it. A reclining chair, or hammock, may also be helpful for remaining comfortable for hours of looking for meteors.

If you want to try to take pictures of this meteor shower, the best way to do that is to use an interchangeable lens camera with a wide-angle lens, at least 20mm, wider if possible. Mount your camera on a tripod and take very long exposures using bulb mode and a remote shutter release cable (but not an app on your phone because you want to preserve your night vision). You might capture a few meteors.

The comet that produces the Orionid meteor shower is the famous comet 1P/Halley. It was observed thousands of years ago in 240 BCE. However, Edmund Halley was the first to make measurements of comets and identify that one comet, in particular, made several visits; it wasn’t a different comet every time like was thought. He made a prediction for this comet’s next appearance. That appearance happened when he predicted, and as he had passed away at that point it was named in his honor as the first known periodic comet.

The next time Comet Halley will make a close approach to the Sun and be visible from Earth is July 27, 2061. The comet’s closest-ever approach to the Earth was back in 887. Its apparent magnitude was as bright as Venus, but because the comet is big and very dark (what we call a low albedo), it was in reality much dimmer.

Comet Halley is one of the most studied comets. An international fleet of spacecraft including two Japanese spacecraft, two Soviet spacecraft, a European spacecraft, and the International Cometary Explorer from NASA and several collaborators, which we mentioned last week, flew by the comet in 1986, observing it from multiple angles.

And while you cannot see the comet itself any time soon, you can lay outside and see some of the dust that that comet has left behind. So go outside and look up. Make sure to stay warm, everyone!

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Hosted by Pamela Gay and Beth Johnson

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.