For this week’s Rocket Roundup, we have exactly zero launches to cover. What’s up with that? In the meantime, we talk about Europa Clipper’s launch announcement, Blue Origin’s attempt to be a part of Artemis, what a NOTAM is, and how we use it. Plus, this week in rocket history, we look back at the launch of the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Podcast

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Pamela Gay and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

One major piece of rocket news this week is the announcement that NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft will launch on a commercial launch vehicle, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, in 2024. This is a big deal for several reasons. Europa Clipper is the first spacecraft to specifically investigate Jupiter’s moon Europa. It will explore the potential habitability of the moon, including confirming the existence of a subsurface water ocean and its composition (if geysers allow), while looking for key compounds related to life. It will also look for signs of recent geologic activity that could provide the energy needed for life. Finally, it will look for a spot for a future lander to set down. All of this science makes Europa Clipper a very large spacecraft, over six metric tons at launch.

Europa Clipper requires a large launch vehicle for its high-energy trajectory. NASA’s Space Launch System was originally intended to send the spacecraft on a three-year, direct flight to Jupiter. However, in early 2021, delays in the development of SLS in addition to concerns about flight conditions led NASA to recompete this launch. Specifically, there were concerns that SLS would shake the spacecraft too much on ascent from a combination of the solid boosters and aerodynamic loads. Two companies, United Launch Alliance and SpaceX were invited to bid after an early draft process.

SpaceX bid their Falcon Heavy rocket and ULA bid their Vulcan Centaur in its largest configuration with six solid boosters. The bids were evaluated on several criteria: past performance, suitability, and cost. Suitability was deemed the most important, followed by past performance and cost. SpaceX’s proposal was deemed suitable, and they were highly rated for having performed numerous past missions with similar requirements using similar rockets.

ULA’s proposal was deemed unsuitable from the start; the proposed rocket was simply not capable of performing the mission. It fell short by about a metric ton. Other factors working against ULA included the fact that they proposed a vehicle that had not flown, yet, so their extensive past performance with Atlas and Delta rockets was not relevant to evaluating the proposal. In addition, the rocket would not be certified to fly the important mission because it would not have enough flight history in the required period before launch. Basically, they proposed something that didn’t fit the required criteria, with being able to lift the payload being one of those criteria.

Based on these factors, SpaceX was awarded a $178.3 million dollar contract to launch the mission in 2024. ULA’s bid was significantly higher, but the specific amount was not stated.

The downside to using the Falcon Heavy instead of SLS is it will take 5.5 years to reach Jupiter, not three, and involve two gravity assists: one from Earth and the other from Mars. This isn’t all bad, as it gives the science team an opportunity to test their instruments on a real target and have time to solve any problems before it arrives at Jupiter in 2030.

This new age of commercial space is going to be weird, and it appears that it is going to include a highly competitive space race between billionaires. I have to admit this was not the sci-fi future I expected to come true.

In an open letter on Monday, Jeff Bezos has offered NASA $2 billion of support from Blue Origin – in-kind contributions in the parlance of grant writers – if his company can be part of NASA’s plans to return humans to the moon. Essentially, if NASA says, “Sure, be part of our plans,” Blue Origin will pay – at least in part – for its contributions.

Backing up a bit, to add some context, NASA had run an open competition to select the rocket of rockets that would be used to deliver spacecraft and humans to lunar space. The original plan was to fund two different rockets and hope that both would succeed while increasing the chances that something would succeed. Unfortunately, Congress didn’t provide NASA with the budget necessary to fund two programs, and in the end, SpaceX was the winning company, and their StarShip, which is still under development, was selected. The Blue Origin proposal was actually part of a multi-company plan put together under the name Blue Moon.

According to the Washington Post: A NASA spokeswoman said the agency was aware of Bezos’s letter but declined further comment, citing pending litigation.

This is an unusual stick and carrot approach, where on one hand, Bezos is offering funding and on the other side, there is litigation. It is going to be fascinating to watch this play out. As our producer Ally stated earlier today: We’re headed for The Expanse.

Take that as you will and just know we live in strange times.

You may have noticed that there were no rocket launches this week. It’s not for lack of trying. We were tracking three different launches this week: one in New Zealand, one in Russia, and one in China. There are outlines of stories all written up and almost ready to go. We literally just needed a rocket, any rocket, to launch.

Some space agencies aren’t shy about telling you what is going to launch when. For example, NASA announces launches at Kennedy Space Center months in advance, and there’s an entire industry in the Space Coast to help tourists see a rocket launch during their vacation.

However, not all launches are publicly broadcasted like that. Astra was so secretive that their job postings didn’t list the company name and instead listed themselves as “Stealth Space Company”. As a team, we usually struggle with Chinese launches (they take us by surprise!). Many weeks, we look at our launch schedule sources to pick stories and struggle to find any, until a Chinese launch pops up with hours of notice.

So, how exactly do we know about upcoming rocket launches? The short answer is that, in addition to the news releases from the various organizations that launch rockets that we subscribe to, we use sites like rocketlaunch.live, where collected information is presented in an easy-to-read format that includes the launch date and time, type of rocket, the company, and, usually, the payload.

And this week, the listing that taunted Annie the most was an unnamed Electron launch by Rocket Lab.

Rocket Lab isn’t generally shy about its launches. Each mission has a somewhat fanciful but memorable name like “Running out of Fingers” or “Another One Leaves the Crust” that deviates from the norm of insert-payload-name-here mission names. Usually, both the payload and mission name are revealed well in advance of a launch.

That wasn’t the case this time.

Rocket Lab released a statement on July 19 where they announced that: Electron will be back on the pad for the next mission from Launch Complex 1 later this month. There were twelve whole days left in July at the time of that announcement. That doesn’t mean we don’t have any info. For example, we can tell you it looks like Rocket Lab is going to launch an Electron on July 29 between 05:30 and 08:30 UTC, but that date has changed at least once during the course of writing the script for this show.

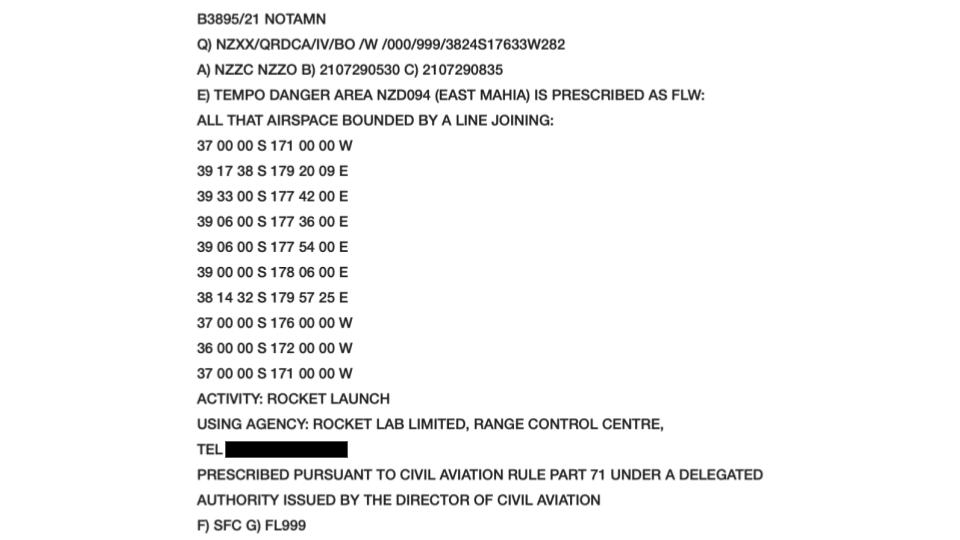

While we don’t have an inside source at Rocket Lab, we do know how to find a NOTAM. A NOTAM, also called a Notice to Airmen, is literally a plain text notice to tell pilots to, among other things, stay out of a certain area bounded by given coordinates and altitudes. This is information that is available to the public at large but used mostly by pilots. They aren’t just issued for rocket launches; they are also issued for things like space debris re-entry or restricted airspace, such as when the President or another important official is travelling. A similar thing called a NOTMAR, or Notice To Mariners, exists for boat captains.

While they don’t tell you what’s going to be on the rocket, NOTAMs can give you an idea of the orbit by the size, shape, and location of the no-go zones.

Finding out the time and date of the launch is the easy part. The hard part is figuring out exactly what payload is going to be put up.

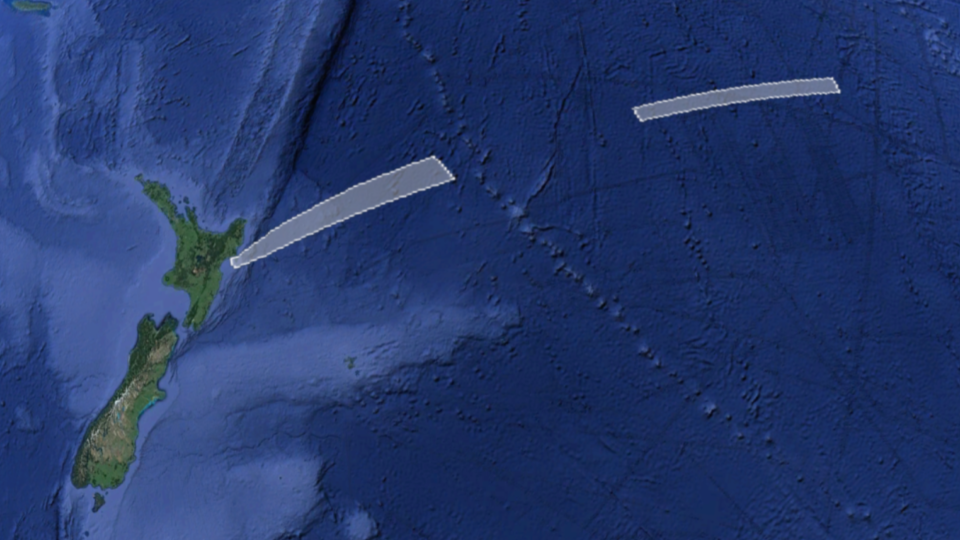

What we do first is to map the coordinates given in the NOTAMs. This launch, for example, had two NOTAMs: one for the launch site and one for a drop zone. The launch site NOTAM turned out to be a very long skinny rectangle stretching out away from the coast of New Zealand. The drop zone NOTAM was another long skinny rectangle further to the east. Based on the shape of the NOTAM no-go zones alone, we can rule out a launch to a polar orbit because those launches have no-go zones aligned to the south.

So, we’re left with a process of elimination. Thanks to Gunter’s Space Page, we know that there are thirteen future Electron launches. After eliminating the ones that don’t take place this year, we’re down to nine. Next, we eliminate the ones that are planned to launch from LC-2 in the U.S., which leaves us with seven possibilities: three BlackSky launches, two Planet Labs launches, one McNair, and one called OTB 3.

Of that list, information about the orbits is available for BlackSky, Planet Labs, and McNair. BlackSky and McNair use orbits with an inclination of 97 degrees, as do the more recent Planet Labs satellites. A 97-degree inclination is a slightly retrograde polar orbit, which has a no-go zone aligned north-south from the Māhia Peninsula rather than the east-west aligned areas described in the NOTAMs.

This leaves us with OTB-3. It’s built by General Atomics, which does a lot of work in the defense sector, and they will also operate it. They’ve also previously announced that OTB-3 wouldn’t launch until late 2021 or early 2022. And although launches tend to slip to later dates rather than be launched earlier than planned, it is still quite possible that the upcoming Rocket Lab launch is OTB-3.

We’ll just have to wait to find out if we’re right.

Minutes before we went live to record this episode Rocket Lab finally confirmed the next mission, STP-27RM for the United States Space Force, aka “It’s A Little Chile Up Here”, launching July 29 at 0600 UTC.

This Week in Rocket History

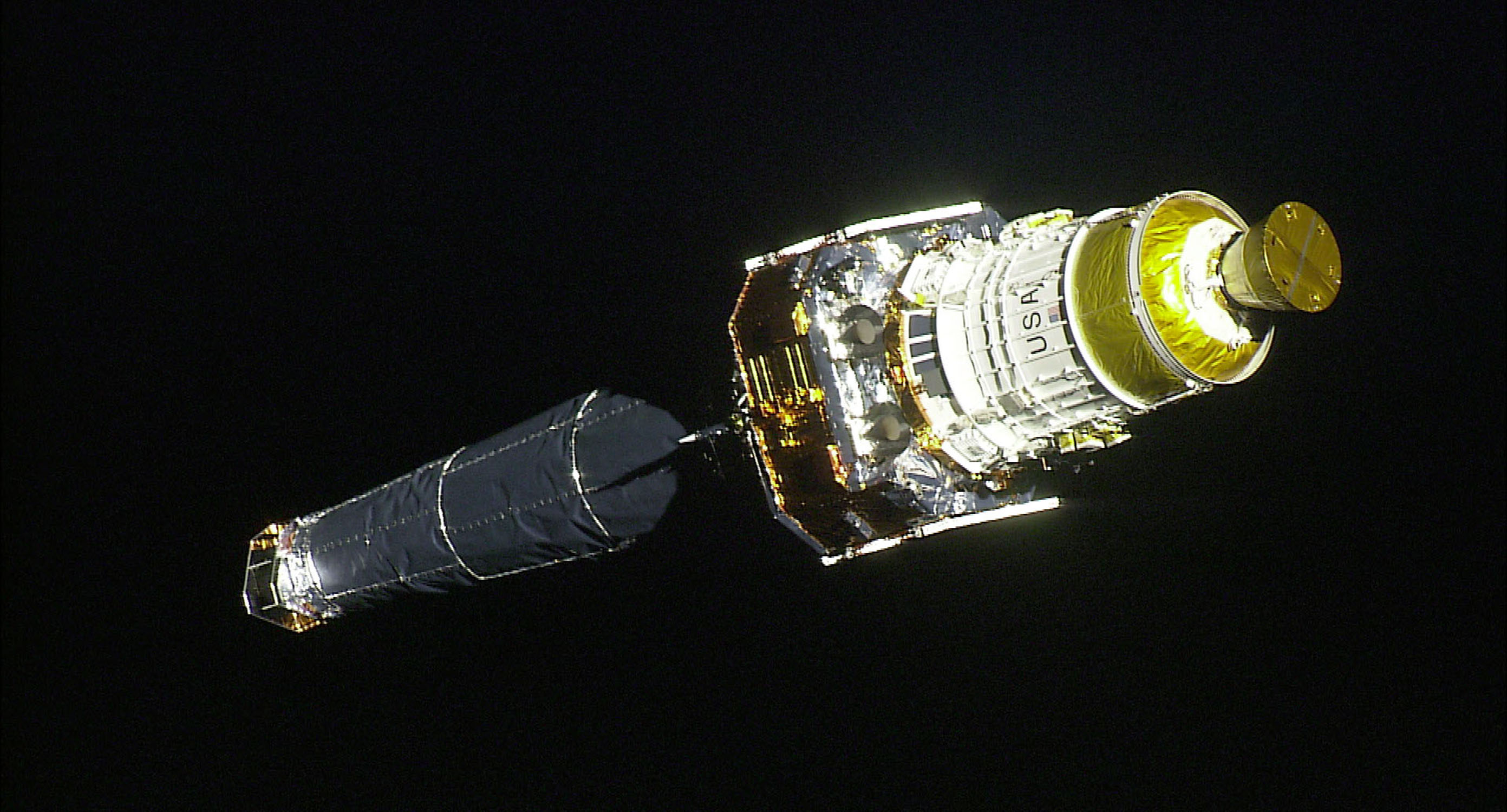

This week in rocket history, we have a groundbreaking mission in x-ray astronomy involving the Space Shuttle Columbia.

STS-93 launched from Kennedy Space Center pad 39B on July 23, 1999, at 16:31 UTC, with shuttle Columbia carrying the Chandra X-ray Observatory. It was the third Great Observatory to launch, after the Hubble Space Telescope and Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. Originally called the Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility, it was renamed after Indian-American physicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar who contributed to the knowledge of white dwarfs and other aspects of stellar evolution. Chandra, which also means “moon” in Sanskrit, was chosen by a student essay contest in April 1998 which received 6,000 entries.

Counting the spacecraft, its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), and support equipment, the payload weighed 22.75 metric tons, the heaviest ever payload launched on the shuttle.

Columbia landed back at KSC on July 28, 1999, at 02:20 UTC after traveling 1.8 million miles in space across a mission duration of 4 days, 22 hours, 49 minutes, and 37 seconds.

Putting this massive telescope in space was necessary because the Earth’s atmosphere blocks the transmission of x-rays. This is, on the whole, good because it means people aren’t constantly barraged by high-energy photons unless you’re an x-ray astronomer. That same protective atmosphere is blocking your perfectly good science. So, in order to study the earliest parts of the universe, scientists need to send equipment to space and hope nothing malfunctions because there’s no practical way it can be repaired. Chandra is also in a very high orbit — 6,731 kilometers by 14,285 kilometers in perigee and apogee, respectively. This orbit was necessary to get the spacecraft above the radiation belts for most of its orbit. It was achieved both with the IUS and the spacecraft’s onboard engine after deployment from the shuttle.

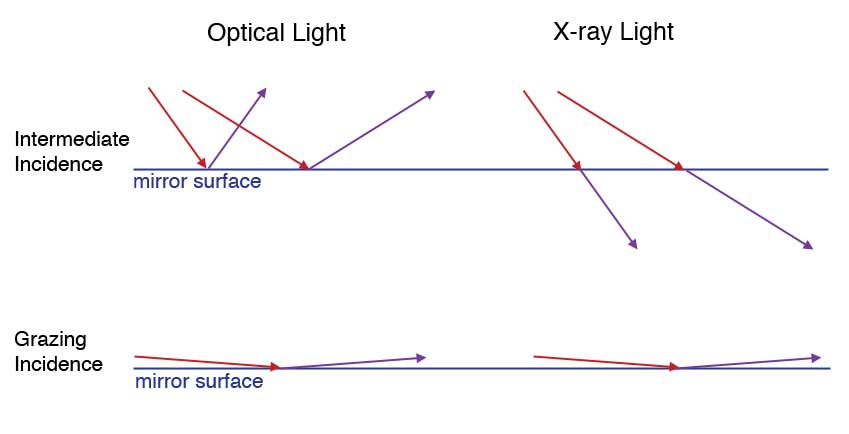

X-ray telescopes are kind of neat because they function differently from optical telescopes. An x-ray photon would go right through a conventional mirror, so to create a focused image, the mirror in an x-ray telescope is almost parallel to the incoming light, creating what is called grazing incidence.

Chandra’s telescope is composed of two sets of four curved mirrors, one behind the other, that each ever so gradually bends the path of those high-energy photons. The combination of this careful and creative engineering and Chandra’s sensitive detectors has made this mission a workhorse many scientists can’t imagine working without. It was only designed to last five years but has kept on producing science for 22 years and counting.

You can expect to keep hearing more about Chandra’s results right here on the Daily Space, hopefully for many more years to come.

Statistics

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 8: 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz, 1 on the Shenzhou, 1 on Tianhe, and 1 on the Nauka module.

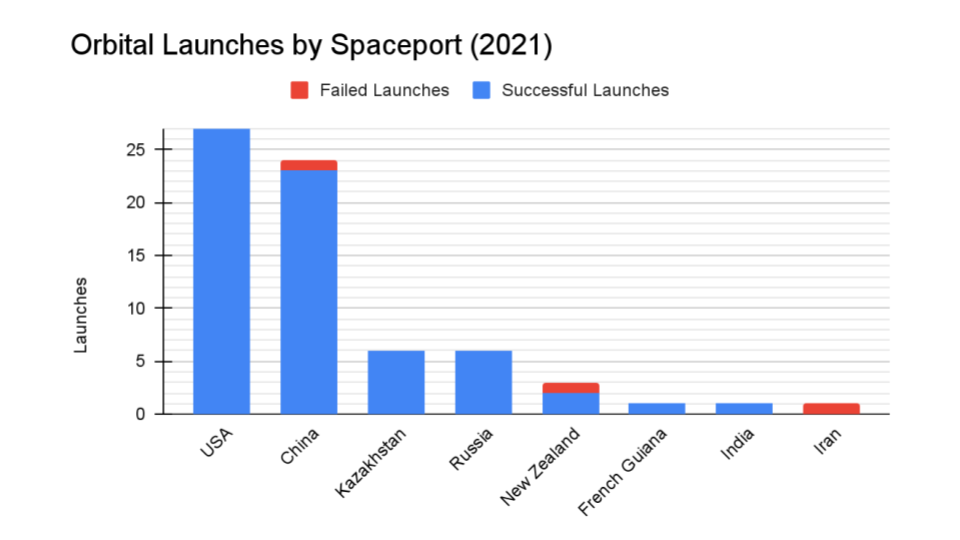

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 69, including 3 failures

Total satellites from launches: 1304

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 27

China: 24

Kazakhstan: 6

Russia: 6

New Zealand: 3

French Guinea: 1

India: 1

Iran: 1

Random Space Fact

Your random space fact for this week is that in 1956, the U.S. Navy sent a message from Maryland to Hawaii by bouncing radio waves off the Moon. The demonstration was pretty crude, with only 10 kilowatts and capable of text transmission or teletype, not images. After improvements to the equipment, the first public demonstration of the Moon Relay came four years later in 1960. An image of sailors standing on the deck of an aircraft carrier was sent from Hawaii to Washington.

Learn More

NASA’s Chooses SpaceX Falcon Heavy for Europa Clipper

Jeff Bezos Offers $2B In-Kind For Artemis Participation

- Open Letter to Administrator Nelson (Blue Origin)

NOTAMs or How to Find Hidden Launches

- From the pandemic to going public: Space startups face hiring challenges (SpaceNews)

- Rocket Lab Completes Anomaly Review, Next Mission on the Pad in July (Rocket Lab)

- General Atomics Partners with Rocket Lab to Launch Argos-4 Advanced Data Collection System (General Atomics)

- Electron info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

This Week in Rocket History: STS-93 and the Chandra X-ray Observatory

- STS-93 (NASA)

- Tyrel Johnson & Jatila van der Veen – Winners of the Chandra-Naming Contest – Where Are They Now? (Chandra Chronicles)

- Chandra X-ray Observatory Quick Facts (NASA)

- Chandra X-Ray Observatory – Orbit (Heavens Above)

Credits

Host: Pamela Gay

Writers: Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.