This Rocket Roundup includes a Chinese launch and two launches from Northrop Grumman, including one for the National Reconnaissance Office. Plus, this week in rocket history, we look back at the first woman in space, cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, and Vostok 6.

Podcast

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

First up, on June 11 at 03:03 UTC, a Chinese Long March 2D rocket launched four satellites into a Sun-synchronous orbit from the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center.

The primary payload was Beijing-3, a commercial remote sensing satellite. It will be used for “land and resources management, agricultural resources survey, ecological environment monitoring, comprehensive urban applications, and other fields.”

Also on board was Heisi-2, a nanosatellite developed for remote sensing of coastal regions including shallow seas and inland water bodies.

The third payload was Yangwang-1, a commercial satellite that will develop technology to be used for future asteroid mining. Yangwang means “look up,” and the satellite is a small telescope described by the manufacturer as a “little Hubble” — although your writing team was unable to determine the actual optical system used. The telescope is sensitive to visible and ultraviolet wavelengths.

The final satellite is Space Experiment 1 Tianjian. It will be used to train satellite operators and also demonstrate a new satellite health management system that is fault-tolerant.

Next up, on June 13 at 08:11 UTC, a Northrop Grumman Pegasus rocket launched the Tac-RL2 “Odyssey” satellite from the last operational Lockheed L-1011 Tristar off the coast of Southern California.

Northrop Grumman, the launch provider, said absolutely nothing about the launch until after it had already occurred. This is fairly unusual for an American launch. There was no live webcast, and there’s no video of the launch. The only public notice was the required aerospace and maritime closures that warned pilots and boat captains that a launch was to take place.

Not much was said about the spacecraft except that it had a “space situational awareness” mission. Built completely from off-the-shelf components, Odyssey was developed by the Space Safari office of the Space Force in less than a year.

This was the second launch in a Space Force program to develop the capability to launch months after a contract is awarded instead of the typical years. TacRL-2 was awarded four months before launch, and Northrop Grumman had 21 days to put the satellite on the rocket and launch it. That’s ridiculously fast for a rocket launch.

The advantage of using Pegasus to launch this mission is its air-launch capability. Because the rocket is carried underneath a plane, it can be launched into any orbit from anywhere with a runway long enough for the plane to take off.

For our last launch of the week, another classified mission. On June 15 at 11:00 UTC, a Northrop Grumman Minotaur 1 rocket launched the NROL-111 mission from Pad 0B at the Mid Atlantic Spaceport Complex in Virginia.

The Minotaur 1 and Pegasus have a few similarities aside from both being launched by Northrop Grumman. They are both small solid-fueled rockets, and Minotaur 1 even borrows the second and third stages from Pegasus as its third and fourth stages. (The first and second stages are from a decommissioned Minuteman 2 ICBM.) Instead of a plane, the Minotaur 1 is launched from a typical launchpad. It makes quite the show, yeeting off the pad in a bright white-yellow streak with a liftoff thrust to weight ratio of 2.6. This is much faster than typical launch vehicles because of the power of its solid motors.

At liftoff, the yellow thermal conditioning blanket peeled off like a banana. On the pad, it helps keep the first stages at just the right temperature, something that would have normally been done by the missile silo it was designed for. It then hung a huge left and shot towards orbit, breaking Mach 1 in twenty seconds.

Like a typical NRO mission, nothing was said about the payloads except that there were three of them.

This Week in Rocket History

This was a slow week for rockets but a great week for history, and we are pleased to dedicate extra time to one of my favorite figures in space flight. For this week in rocket history, we look back at the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, and her flight aboard Vostok 6.

But first, some more history to put everything in context.

In the early 1960s, an American physician named William Lovelace set out to demonstrate something that we now take for granted: that women were also capable of being astronauts and might even be better suited for long missions due to their small physical size and associated lower intake of resources. In the summer of 1961, a record-holding pilot named Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb took and passed the same tests as the Mercury 7 male astronauts, which included eye exams, a special weighted stationary bike, and a moving table that tested their circulation. A private organization was unofficially testing a group of women that are now retroactively called the “Mercury 13” by a Hollywood producer.

These women were not associated with NASA in any way and were being tested to determine suitability, not being trained to go to space. A year later, nineteen more women took the same tests. Although thirteen of them qualified by the same standards set for the male Mercury 7 astronauts, they never became astronauts — even after they went in front of Congress to make their case.

Nikolai Kamanin, head of the Soviet cosmonaut training program, read news reports about Cobb and the other women that could potentially be astronauts. He decided that the USSR had to beat the Americans. The United States absolutely could not be the first country to put a woman in space. In early 1962, twenty-three final candidates for five female cosmonaut slots were brought to the training center for evaluation. After several months of tests, the five were chosen to undergo basic astronaut training which took the rest of 1962. The final decision on who would fly was in May 1963.

Keep in mind that all of this was taking place in the backdrop of the Space Race and Cold War. The USSR and the United States were competing to show the rest of the world whose economic system was better while also building and pointing nuclear weapons at each other and waiting for the other side to blink.

The criteria for a female cosmonaut was “young, brave, physically strong, with aviation experience, and able to be trained for spaceflight in less than six months”. They also had to be under the age of 30, shorter than 170 centimeters (just over 5 and a half feet), and know how to parachute. Both male and female cosmonauts didn’t need too much in the way of specialized training for the Vostok spacecraft as the flight was largely controlled from the ground. This simplified the rushed process for selecting a female cosmonaut from 400 potential candidates.

From that list of 400, five candidates were chosen:

- Tatyana Kuznetsova, world record holding parachutist

- Valentina Ponomaryova, pilot and graduate of the Moscow Institute of Aviation

- Irina Solovyeva, veteran of over 2000 parachute jumps

- Zhanna Yorkina, amateur parachutist

- Valentina Tereshkova, amateur parachutist and textile worker.

Valentina Tereshkova had been interested in aviation for a long time, training to be a competitive skydiver while at her job in a textile factory. Her widowed mother didn’t approve of this so she had to go to the training facility in secret. She made her first jump at the age of 22 in 1959.

Yuri Gagarin, who at this point had already flown into space, decided to be a mentor and guide to the new female cosmonaut candidates. The other male cosmonauts weren’t too happy about them, seeing their presence as taking seats that were rightfully theirs.

The first step in the training of the female candidates was basic flight school in both fighters and cargo planes. With this done they were now Junior Lieutenants in the Soviet Air Force, a requirement to become a cosmonaut.

Kuznetsova and Yorkina withdrew from training later, due to illness and “poor performance”. Valentina excelled at everything from the centrifuge to the isolation chamber to parabolic flights, in addition to theoretical tests on spaceflight topics. She was selected in May 1963 by Kamanin to fly Vostok 6, a joint mission with Vostok 5. Vostok 5 was to be commanded by Valery Bykovsky. Irina was to be Tereshkova’s backup. Tereshkova was selected not just because of her physical and academic qualifications but also because she had the right background that the Soviets wanted to present to the world. She grew up working on a farm, currently worked in a textile factory, and was single with a good work ethic.

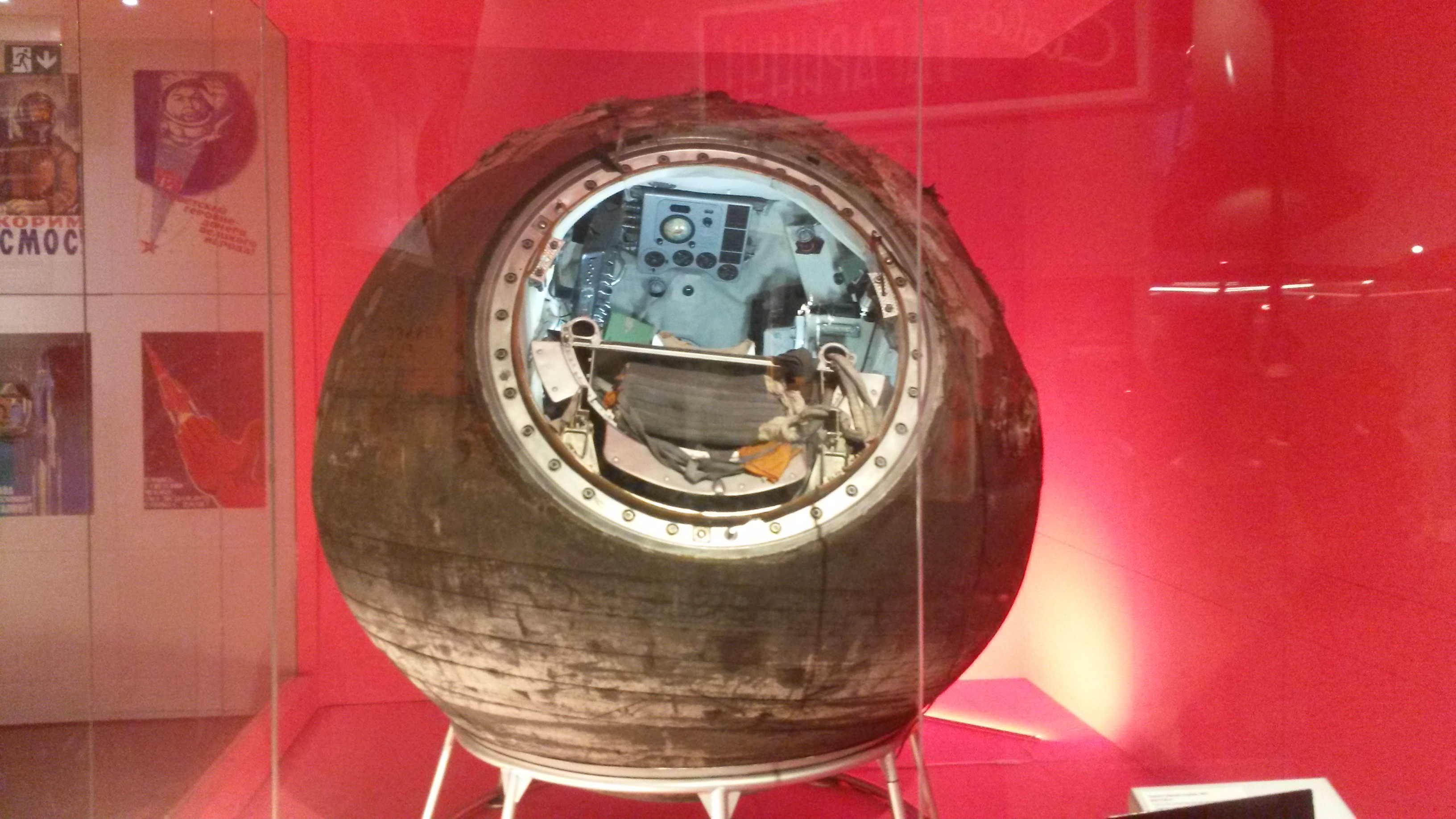

The primary goal of Vostok 6 was to investigate the effects of zero-g on the female body as well as operations between two spacecraft in orbit. Vostok 6 launched on June 16, 1963, at 09:29 UTC with Tereshkova, now the first woman to go into space. The launch was nominal, unlike the slight third stage underperformance that left Vostok 5 in a lower than intended orbit. According to telemetry, Tereshkova’s blood pressure and heart rate were lower than her comrade’s during his launch.

On her first orbit, she came within five kilometers of Vostok 5 and Bykovsky (who launched two days prior) for a planned rendezvous. A proper rendezvous would have had the two spacecraft come much closer to each other — within tens of meters — but the Vostok spacecraft weren’t able to do the maneuvers needed to make that happen. Direct communication between Vostok 5 and 6 was impossible after the first day as the spacecraft drifted apart.

Unlike Bykovsky, Tereshkova had more success observing the Earth and stars through the Vzor periscope and porthole. She took several video recordings of forests and streams passing below from inside the spacecraft. Tereshkova threw up once after eating particularly dry bread, and unfortunately, that wasn’t the only problem encountered on the flight. On her first day in orbit, she noticed a problem with the deorbit motor. If it had fired as intended, instead of coming back to Earth she would have been sent to a higher orbit, where her life support would have been depleted before the spacecraft’s orbit decayed due to atmospheric drag. This, quite frankly, would have killed her. Luckily the programming was fixed and the deorbit on the third day of the mission was nominal.

She could have stayed in space longer but returned because Vostok 5 had problems that caused the mission to end earlier than planned as it was simpler to bring both capsules back at the same time. Unlike Vostok 5, her service module even separated cleanly from the orbital module. The Vostok didn’t carry a big enough chute to allow a soft landing with the cosmonaut on board, so they had to eject and parachute down themselves, which was why being a parachutist was a requirement. She landed on her back but was quickly helped by locals. Because she landed in a remote location, it took her three hours to inform ground control that she had landed safely. Vostok 6 was the last Vostok mission.

Tereshkova never flew again — to space or otherwise — because of her importance to the state, especially after Gagarin was killed in a training accident in 1969. She traveled the world in carefully scheduled tours, with the Soviets displaying their “ordinary” hero to the world.

Statistics

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 6: 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz, and 1 on Tianhe

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 54, including 2 failures

Total satellites from launches: 1152

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 24

China: 17

Kazakhstan: 4

Russia: 4

New Zealand: 3

French Guinea: 1

India: 1

Random Space Fact

Your random space fact for today is that the first stage motor used on the NROL-111 launch this week was manufactured 54 years ago.

This has been the Daily Space.

Learn More

CASC launches four small satellites

Space Force tests short award-to-launch program

- Northrop Grumman press release

NRO launches NROL-111 from Virginia

This Week in Rocket History: Vostok 6

- Vostok 5 info page (Astronautix)

- Vostok 6 info page (Astronautix)

- Lovelace’s Woman in Space Program (NASA)

- World First Woman Cosmonaut Speaks About Error of Vostok Designers (Kommersant via Internet Archive)

- BOOK: The first Soviet cosmonaut team: their lives, legacy, and historical impact (Archive.org)

- BOOK: Women in Space – Following Valentina (Google Books)

- BOOK: Valentina Tereshkova, The First Lady of Space: In Her Own Words (Amazon)

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Elad Avron, Dave Ballard, Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.