In this week’s Rocket Roundup, host Annie Wilson presents not one but two SpaceX Starlink launches as well as two Chinese launches. Plus, this week in rocket history, we look back at the Gemini 8 mission, which launched March 16th, 1966.

Media

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

First up this week, on March 11 at 08:13 UTC, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 Booster 1058 launched the L-20 mission, putting another sixty Starlink satellites to orbit from SLC-40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. The launch took place in the middle of the night.

For those of you keeping score at home: this was the sixth mission for the booster, and one of the fairings had flown on two previous missions, while the other fairing had only previously flown once.

Booster 1058 successfully landed on the barge Just Read The Instructions, which was stationed 663 kilometers downrange. The fairings were recovered from the water by the GO Searcher and GO Quest recovery ships.

About nine hours later that same day, at 17:51 UTC, a Long March 7A successfully launched the Shiyan 9 satellite from the Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Center, which is on the island of Hainan along the southern coast of China.

This marked the second launch of a Long March 7A. According to Chinese media, the satellite is for “in-orbit verification tests of new technologies such as space environmental monitoring.” Put another way, just like NASA, China sometimes launches payloads just to see if a new toy will work, and in this case, the new toys will monitor the conditions in space around the satellite.

This was the second launch and first successful launch of this new rocket configuration.

Around the time of this launch, information about the Long March 7A launch failure last year was released. After a very quick, but very thorough, fault tree investigation of just twenty days, Chinese engineers determined the cause of the failure was cavitation in the booster tank. Cavitation is a fancy way of saying that the fuel had bubbles in the mix, and this changed how the fuel burned. In this case, it was not in a good way. Those bubbles prevented the usual amount of fuel from reaching the engine. Less fuel means lower thrust. Unfortunately, that lower thrust couldn’t be compensated for by the upper stages of the rocket, and it ultimately failed to reach orbit.

The investigation was followed by numerous tests conducted over the next three months to come up with a fix for the problem. Exactly seven months after the initial failure, the fix was proven successful by this launch of the Long March 7A.

Next up, on March 13 at 02:19 UTC, the Yaogan 31-04 mission took off atop a Long March 4C rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwestern China.

This was the fourth trio of Yaogan 31 satellites launched for this constellation, with the first three batches going up on April 10, 2018, and earlier this year on January 29 and February 24.

“Yaogan” translates to “Remote Observing,” so it makes sense that the China Academy of Space Technology stated after one of the previous launches that the satellites “will be mainly used to carry out electromagnetic environment detection and related technical tests.”

Finally, on March 14 at 11:01 UTC, a SpaceX Falcon 9 lofted another sixty Starlink satellites to orbit for the Starlink L-21 mission from LC-39 at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. This was the ninth mission for Booster 1051 — a new record for SpaceX. Like the other Starlink launch, the fairings had both previously flown, in this case on the Transporter-1 mission back in January of this year.

All sixty satellites were deployed into orbit successfully. Booster 1051 made its ninth landing on the barge Of Course I Still Love You. Both fairings were recovered from the water by GO Searcher and GO Quest.

To accommodate the rapid launch cadence, the GO “twins” dropped off the fairings from L-20 in a port in North Carolina so it could head back out to the landing zone for L-21. Another ship transported L-20’s fairings from North Carolina back to the Cape. After recovering L-21’s fairings, GO Searcher and GO Quest headed directly to Port Canaveral after recovering the fairings, arriving before Of Course I Still Love You and B1051 in the afternoon of March 16th. We have a photo of this event thanks to DrWD40, who went out to stream the return in Florida. Thanks for letting us use the image.

By our team’s tally, 1,263 Starlink version 1.0 satellites have been deployed so far, which is approximately 88% of the first phase. Three more Starlink launches, or 180 satellites, should complete the first shell of the constellation. With the current rate of launches, the CosmoQuest team expects this to happen as soon as April or May of this year, though because space is hard, it might mean June. We would add one caveat: a certain number of Starlinks fail for various reasons, so an additional launch may be needed to top numbers off. Because the satellites have finite and relatively short lifespans, it will be necessary to periodically add new satellites to the constellation as older ones are decommissioned.

For us, that means more launches to watch.

Most of the time when the International Space Station needs to get rid of the trash, the crew just stuff unneeded items into a used cargo capsule. When it gets full, they drop it into the atmosphere where the capsule burns up. At least, this is what usually happens. Just like how garbage trucks occasionally leave items behind, the astronauts sometimes have waste that is too big to go in that outbound cargo craft turned trash can.

For the ISS, Thursday, March 11, was the big garbage day. A three-ton pallet of old nickel hydrogen batteries had been hanging around, unused, on the outside of the station, and the time to finally throw them out had come.

These batteries had provided the station with power, but, like all batteries, the day came when they needed to be replaced. They got set aside rather than thrown out because three tons of batteries is a bit big for most of the cargo vehicles.

Astronauts using the ISS’ Canadarm released the pallet of old batteries from the side of the station and sent it on its way. These discarded batteries are the largest object ever jettisoned from the Space Station. The pallet is expected to re-enter the atmosphere in a few years. Until then, it will be yet another object for new fleets of low orbiting commercial spacecraft such as CubeSats and SpaceX’s Starlinks to maneuver around as they raise themselves into their operational orbit.

In general, this is not how batteries should be disposed of people.

For the longest time, the astronauts had done exactly what so many of us do; they had kept the dead batteries hanging around in a box, or in their case on a pallet.

This unceremonious jettison was necessary because a Japanese HTV spacecraft that could have brought the batteries down in a controlled destructive re-entry was unavailable. The ascent abort of Soyuz MS-10 in 2018 caused a ripple-effect that delayed the schedule for replacing the old nickel batteries with new lithium ion batteries. This resulted in one of the HTV spacecraft returning empty, leaving an extra set of old batteries on the station.

Prior to this pallet of old batteries, the largest thing that had been released from the ISS was a 635-kilogram tank of ammonia from an interim ISS cooling system that was released during an EVA in 2007.

While this jettison will make life more complex for other spacecraft for the next few years, this does have the same eventual outcome that an HTV spacecraft would have allowed: the batteries will burn-up in the upper atmosphere where it can’t affect life or pollute our world.

Don’t try this method of battery disposal unless you are in space..

This Week in Rocket History

This Week in Rocket History we have another historic mission as well as the birthdate of an important astronaut.

On March 16, 1966, at 15:00 UTC, an uncrewed Atlas Agena was launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida with a Gemini-Agena Target Vehicle, also known as GATV. It was followed 101 minutes later by a Titan II Gemini Launch Vehicle, a specialized version of the Titan II ICBM, carrying astronauts Neil Armstrong and David Scott onboard Gemini 8.

Gemini 8 chased down the Agena, and performed nine different maneuvers over a period of six hours, eventually bringing it to within 45 meters of the uncrewed Agena. After another hour of tests and inspections, the astronauts performed their final maneuver and completed the first ever docking of two spacecraft in orbit.

The original mission plan was to perform four different dockings and multiple tests including a spacewalk, but 27 minutes after the first docking, both crafts started unexpectedly tumbling on all axes. The astronauts suspected the issue might be coming from the Agena, so Scott disengaged the capsule from the GATV, and Armstrong maneuvered the Gemini away from the Agena, but they were still spinning, and it was getting worse. This indicated that the issue must have come from Gemini itself.

As Gemini 8 tumbled at speeds exceeding one revolution per second, the astronauts were close to blacking out and didn’t have a lot of time to react. They quickly deactivated the automated maneuvering system and attempted to counteract the violent motion of the spacecraft using their re-entry reaction control systems thrusters, eventually managing to stop the roll and stabilize the spacecraft.

Safety protocols for the mission dictated that once the re-entry reaction control systems thrusters were engaged, the crew had to end the mission and come back to Earth immediately. This meant that any further tests and the planned EVA were cancelled. After another orbit, the capsule fired its retro-rockets and deorbited into the Pacific Ocean. USAF Frogmen parachuted out of a C-54 near the splashdown site to put flotation devices around the capsule and make sure the astronauts were safe until they were picked up by the U.S.S. Mason some three hours later.

Post-flight investigations determined that the unexpected roll was caused by one of the roll thrusters firing continuously, but the investigation could not determine what caused the thruster to begin firing in the first place. It did, however, prompt NASA to add a dedicated kill switch for each element of the capsule in follow-up missions.

Neil Armstrong would go on to command the first crewed lunar landing, Apollo 11. David Scott made it to the lunar surface as well, commanding Apollo 15 and driving the first Lunar Roving Vehicle.

March 16th also marks the birth date of Vladimir Komarov. Born in 1927, he was selected as part of the first group of Soviet cosmonauts in 1960, but a heart condition prevented him from being cleared to fly into space until Voskhod 1 in October 1964.

Voskhod 1’s goal: fly a three-person crew in a capsule before the Americans could. The Voskhod used the same basic spacecraft as the single person Vostok, so it was a tight fit with three crew members. To make room in the craft, the backup deorbit motor was removed, and the cosmonauts went without pressure suits. During their time in space, the crew was able to learn how to perform operations in a multiple crew spacecraft, observed the Earth from orbit, and recorded how the human body responded to weightlessness. The crew returned to Earth after one day in orbit.

Komarov’s other mission was Soyuz 1, the first crewed flight of the Soyuz spacecraft. Unlike the nearly flawless mission of Voskhod 1, this mission was plagued by failures from the beginning.

The first launch attempt was aborted.

Another launch attempt was made, and this time, Soyuz 1 left the pad. As soon as the spacecraft separated from the rocket the problems began. Only one of the solar panels deployed, which left the craft with less power than it would usually receive. The radio failed, so communication with the ground was intermittent. The horizon sensor also failed, so Komarov couldn’t determine his spacecraft’s attitude for burns. Ground control decided to end the mission early. The automatic system for deboritting was triggered on the sixteenth orbit and failed. Komarov manually performed the deorbit burn two orbits later.

Thankfully, re-entry was normal and the drogue chute deployed. The main chute, however, failed to deploy because it was tangled. The reserve chute was deployed, and that ended up being tangled with the drogue chute.

Without any parachutes, Soyuz 1 was unable to slow down enough for a safe re-entry. It impacted the ground at speed, destroying the spacecraft, and killing Komarov.

His remains were recovered, and he was given a state funeral in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow. After his death, he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union, the highest award in the country for bravery. A bust of Komarov on a pillar was erected at the site of the crash as a memorial.

Statistics

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Estimated number of toilets currently in space: 5: 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz. We are still looking into getting an official number.

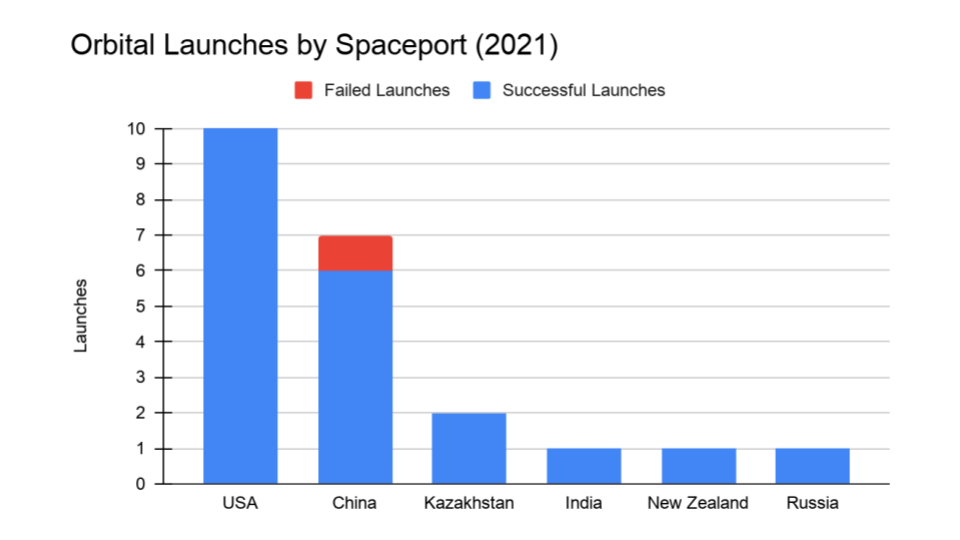

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 22, including 1 failure

Total satellites from launches: 548, with just over two thirds of those being Starlinks

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 10

China: 7

Kazakhstan: 2

India: 1

New Zealand: 1

Russia: 1

Random Space Fact

Last week, I told you about a couple of people whose ashes had flown in space. This week, I want to tell you about a piece of an apple tree that flew on the space shuttle to the International Space Station.

As part of the celebrations for the 350th anniversary of the Royal Society, of which Isaac Newton was a former president, NASA astronaut Piers Sellers brought a fragment of the apple tree that inspired Newton’s discovery of gravity in 1666 with him when he flew on STS-132, the last flight of the shuttle Atlantis to the International Space Station.

Though the tree still stands at Woolsthorpe Manor in Lincolnshire where Newton lived, pieces of it were stored in the Royal Society’s vaults in the 1700s, along with a lot of other Newton memorabilia.

The piece of Isaac Newton’s apple tree that went with him was about 10 centimeters long and even had a little marking from the 17th century that read “I. Newton”. No one knows if it was inscribed by Sir Isaac himself.

According to an article in The Guardian that appeared shortly before the twelve-day mission in May 2010, Sellers said that he will “…take it up and let it float around for a bit, which will confuse Isaac.” He went on to say that: While it’s up there, it will be experiencing no gravity, so if it had an apple on it, the apple wouldn’t fall… Sir Isaac would have loved to see this, assuming he wasn’t spacesick, as it would have proved his first law of motion to be correct.

And where is it today? At the time, Martin Rees, the then president of the Royal Society, stated that: [u]pon their return the piece of tree and picture of Newton will form part of the History of the Royal Society exhibition that the Society will be holding later this year and will then be held as a permanent exhibit at the Society.

This has been the Daily Space.

Learn More

SpaceX Launches Starlink Batch During Nighttime Launch

China Sends Shiyan 9 Into Orbit to Test New Technology

- Spaceflight Fans article (Chinese)

- Shiyan 9 info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Long March 7A failure article (Chinese)

- Launch video

Fourth Trio of Yaogan 31 Satellite Constellation Launched

Starlink L-21 Launches Successfully, Booster Breaks Record

Space Station Crew Takes Out the Trash

- Gizmodo article

- Houston Chronicle article

This Week in Rocket History: Gemini 8 and Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov

- Gemini’s First Docking Turns to Wild Ride in Orbit (NASA)

- Gemini 8 archive (NASA)

- We Start The First Voskhod Mission (Zarya)

- Vladimir Komarov (Zarya)

- Soyuz 1 info page (Spacefacts.de)

Random Space Fact: Sir Isaac Newton’s Apple Tree

- Newton’s famous apple tree to experience zero gravity (The Royal Society)

- Isaac Newton’s apple tree to experience zero gravity – in space (The Guardian)

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Elad Avron, Dave Ballard, Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.