Not every day is equal. Some days are rockier than others. Take today for example, we have three stories that involve rocks, ice, and other stuff that can really wreck your day. Join us as we discuss the Allan Hills Meteorite ALH84001, Asteroid 1998 OR2’s 6 million km miss; & Comet Atlas’s exquisite death.

Links

The Allan Hills Meteorite ALH84001

Asteroid 1998 OR2’s 6 million km miss

Comet Atlas’s Exquisite Death

- Hubble Captures Breakup of Comet ATLAS (Hubble Space Telescope)

- Hubble Watches Comet ATLAS Disintegrate into Dozens of Pieces (Hubblesite)

Transcript

This is the Daily Space for today, Thursday, April 30, 2020. I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay, and I am here to put science in your brain.

Not everyday is equal. Some days are rockier than others. Take today for example, we have three stories that involve rocks, ice, and other stuff that can really wreck your day.

In our first story, we have news from Japan. The Earth-Life Science Institute at the Tokyo Institute of Technology has announced the discovery of organic compounds containing nitrogen in a Martian meteorite. This alien rock was ejected from Mars, most likely during a massive impact about 15 million years ago, and traveled to Earth, where it was picked up by researchers in Antarctica in 1984.

This particular rock was already famous. Dubbed the Allan Hills Meteorite, or just “That Mars Meteorite”, this rock, ALH84001, was at the heart of 1996 claims that nanobacteria had been found in a Martian meteorite. These claims were based on the shape of mineral structures in the rock that resemble formations of extremophiles on Earth; however many researchers have tried to debunk these claims, both by explaining that what is being seen in scanning electron microscope images could be a mistake in sample preparation, and by finding other ways to create these sample shapes.

This new research on the same rock doesn’t just look at the mineral shapes, and it makes no claims about finding lifeforms. Instead, it looks at the chemical composition of the rock. They have found orange-colored carbonate grains that are consistent with minerals forming in organic-rich water. This Orthopyroxene rock could have formed 4 billion years ago on Mars in an aquatic surrounding – the kind of surroundings where life could have either formed or thrived. After Mars dried out, this rock would have sat in an increasingly inhospitable landscape until an impact sent it on its interplanetary journey.

The folks at the Earth-Life Science Institute were fully aware of the earlier controversy and wanted their own work to be above board. As described in the press release, to make sure they avoided contamination, “the team developed new techniques to prepare the samples with. For example, they used silver tape in an ELSI clean lab to pluck off the tiny carbonate grains, which are about the width of a human hair, from the host meteorite. The team then prepared these grains further to remove possible surface contaminants with a scanning electron microscope-focused ion beam instrument at JAXA. They also used a technique called Nitrogen K-edge micro X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (µ-XANES) spectroscopy, which allowed them to detect nitrogen present in very small amounts, and to determine what chemical form that nitrogen was in. Control samples from nearby igneous minerals gave no detectable nitrogen, showing the organic molecules were only in the carbonate.”

Now, the presence of nitrogen containing organic compounds doesn’t mean Mars had life. It means that Mars had conditions consistent with life as we know it here on Earth. What this rock means is that we need to develop the technology to go fossil hunting on Mars, because the odds are becoming ever more in our favor that we just might find something etched in Mars’ now-dead surface.

The impact that sent the Allan Hills Mars Meteorite to Earth was a lucky strike for us. It didn’t hit our world – so good. It also sent us some of our only samples of the Red Planet – so good for science! These kinds of strikes were exceedingly common in the early universe, but have become less common as our solar system has used up some of its asteroid ammunition. That doesn’t mean we don’t have to be on the lookout for incoming asteroids, however. In fact, yesterday morning a 2 km wide asteroid, 1998 OR2 flew past us at 19,461 miles per hour at a distance of 6.2 million kilometers. This distance meant it was close enough for scientists to get cool data, but also more than 15 times farther away than the moon, and thus not a danger. While we aren’t seeing a bunch of cool images yet, I for one look forward to the new science that will come from this fairly large miss.

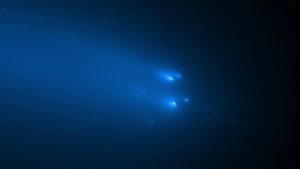

Asteroids aren’t the only things tearing through our solar system, and periodically careening into worlds. We also have comets to contend with, but when it comes to comets, our Sun and it’s light and gravity do their best to destroy these nemeses, even when we don’t want them too. Recently, we were all looking forward to seeing Comet Atlas fly past earth as an easily visible object. Before that could happen, however, it fell to pieces. But hey, it fell to pieces in style, and the Hubble Space Telescope is taking amazing images of its demise. In images that are only a few days apart, the fragments can be seen moving and varying in brightness. Team scientist David Jewitt has noted “Their appearance changes substantially between the two days, so much so that it’s quite difficult to connect the dots. I don’t know whether this is because the individual pieces are flashing on and off as they reflect sunlight, acting like twinkling lights on a Christmas tree, or because different fragments appear on different days.” While I remain disappointed that 2020 keeps taking away our comets, I am enjoying the remarkable imagery we’re getting of this one’s exquisite death.

And that rounds out our show for today.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.