SpaceX launched another 49 Starlink satellites last week, but a geomagnetic storm caused by solar activity kept the satellites offline, and 40 of them failed to reach their final orbits after exiting safe mode. They are now deorbiting and breaking up in the Earth’s atmosphere. Plus, asteroid systems, Eta Carina, and this week in rocket history, we look back at Mir Expedition 2.

Podcast

Show Notes

Found: Youngest pair of asteroids

- Lowell Observatory press release

- “Recent formation and likely cometary activity of near-Earth asteroid pair 2019 PR2–2019 QR6,” Petr Fatka et al., 2022 February 2, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

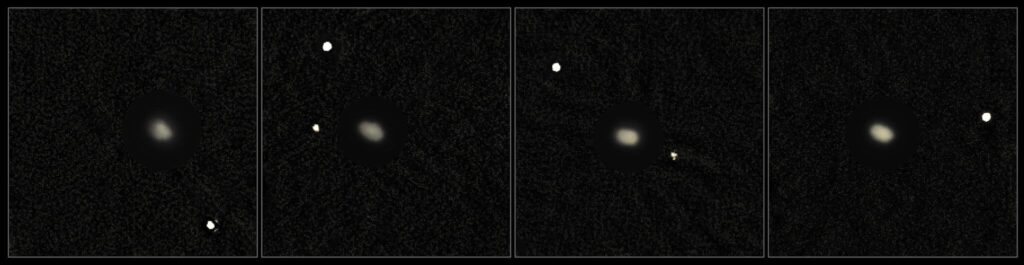

Found: A third moon for asteroid 130 Elektra

- The First Quadruple Asteroid: Astronomers Spot a Space Rock With 3 Moons (The New York Times)

- “First observation of a quadruple asteroid,” Anthony Berdeu, Maud Langlois, and Frédéric Vachier, 2022 February 8, Astronomy & Astrophysics

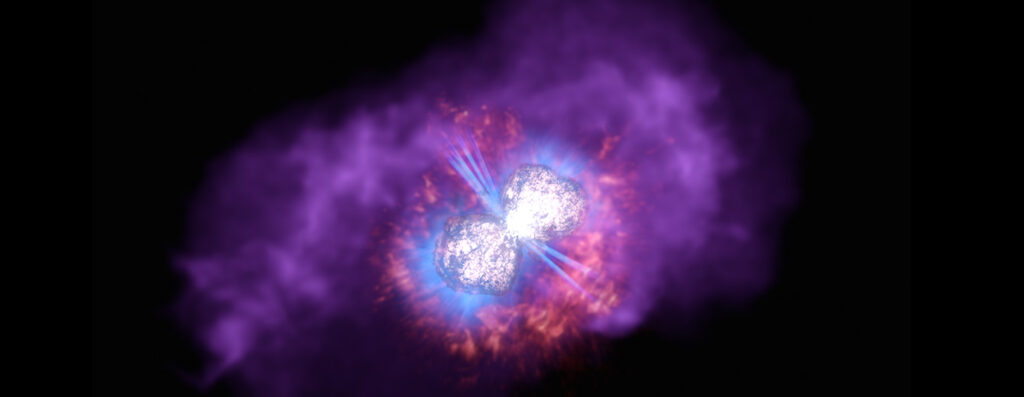

New Visualization of Eta Carina released

- Hubble press release

Starlinks doomed by solar flare

- SpaceX press release (via archive.today)

This Week In Rocket History: Mir Expedition 2

- PDF: Mir Hardware Heritage (NASA via Internet Archive)

- Soyuz TM-2 info page (Astronautix)

- Soyuz TM-3 info page (Astronautix)

Transcript

Science doesn’t rest for the weary, and today’s news was last night’s late-night tank watch of Mechzilla lifting Starship 20 onto Booster 4. While it went up, we also have news of Starlinks coming down.

And science. We also have asteroids, stars flaring up, and more coming up on Daily Space.

I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay.

And I am your host Beth Johnson.

And we’re here to put science in your brain.

We are constantly scanning the skies these days for any and all threats, be they terrestrial or astronomical. Several of those surveys are looking for space rocks because, well, remember the dinosaurs? They didn’t have a planetary defense office and look what happened to them. They’re now chickens.

Last week, we told you how the ATLAS survey has now expanded to two more countries, for a total of four observatories, which can scan the entire night sky in both the northern and southern hemispheres. This next story is about a different survey telescope: Pan-STARRS1 in Hawai’i. You may recognize the name because, like ATLAS, there are quite a few Comet Pan-STARRS in the books. And just as ATLAS can find comets and asteroids, so too can Pan-STARRS.

Back in 2019, an asteroid named 2019 PR2 was discovered in the Pan-STARRS observations. Then the Catalina Sky Survey announced the discovery of a second asteroid in the same vicinity, 2019 QR6. And this week, Lowell Observatory in Arizona confirmed the two asteroids in follow-up observations and announced that they are from the same parent body. Not only that, but they only split off from that parent body, whatever it was, about 300 years ago.

If Galileo had been able to search for these asteroids, he would have only seen one, not this tiny pair, the largest of which is a mere kilometer in diameter.

One of the really interesting aspects of this discovery is that it once again involved the use of precovery data. Scientists went back through the Catalina Sky Survey data and found the pair in observations taken fourteen years ago. With that data and the more recent observations, they were able to determine very precise orbital elements, and that helped them conclude the two were once one and separated basically this morning.

The paper on this discovery is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and lead author Petr Fatka notes: To have a better idea about what process caused the disruption of the parent body, we have to wait until 2033 when both objects will be within the reach of our telescopes again.

We look forward to bringing you the results of that observation when it happens.

What’s cooler than an asteroid pair? How about an asteroid trio? Asteroid 130 Elektra is pretty special in this regard – it has two moons and is a rare triple asteroid. The asteroid itself was discovered back in 1873 in the main belt. Elektra is kind of oblong and over 250 kilometers on the longest side. It orbits the Sun every five years. The first of the two moons was discovered back in 2003 and the second in 2014. Still, an asteroid with two moons is not unheard of, even it’s pretty interesting.

But wait, there’s more! Astronomers using the Very Large Telescope in Chile have announced the discovery of a third moon for the tiny system, and that makes this a first for our solar system.

Now, none of these moons are very big. The largest of the three and the first one discovered is about six kilometers in diameter. The next one is about two kilometers across, and this latest one is smaller than that, at 1.6 kilometers. All three orbit their parent asteroid, Elektra, in periods ranging from less than a day for the smallest and just over five days for the largest. However, the orbit of this newest moon is out of alignment with the other two, which makes this an excellent system for follow-up studies about the stability of asteroid systems.

Again, this system is probably the result of a collision between Elektra and another body, which broke off the three tiny moons. Observations so far show that the four pieces are all made of the same materials. More data is needed, and the team hopes to use the new Extremely Large Telescope once it’s completed and operational to see if there are any more moons in this system and if there are any more asteroids with three moons.

The discovery of 130 Elektra’s third moon was published in Astronomy & Astrophysics with lead author Anthony Berdeu.

While rocks in space are very much a safety concern for people on Earth, stellar expansion, flares, and eruptions are really the ultimate solar system enders. Folks down in the southern hemisphere have had a rather spectacular view of the evolving end of the Eta Carina system. This fairly mundane star that was good for navigation underwent an outburst in 1843 and then faded out of view before re-brightening in 1887. In the modern, space-based observing era, researchers have resolved the details of this system across many different wavelengths that resolved the great hourglass clouds expanding from the central stars – Eta Carina is thought to be a binary system – and by looking at the system in different wavelengths, the different densities of materials have been revealed.

Now, data visualization experts at the Space Telescope Science Institute have combined Hubble and Spitzer’s visual and infrared data with X-ray data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory to create a stunning new visualization that brings together a wealth of scientific information in a format designed to be accessible to everyday people. We will link to all the visualization information on our website, DailySpace.org.

Next up, we take a look at a Starship going up, and a whole bunch of Starlinks coming down.

If our team seems a bit tired today, it’s because Erik and I stayed up late last night watching the stacking of Starship 20 onto Booster 4. This was done without humans guiding the action with hands and ropes! Instead, Starship was lifted in the chopsticks on Mechzilla, and while the booster was held in place with the QD arm, Starship was lowered into place. While SpaceX is still waiting for FAA approval to launch this massive rocket from Boca Chica, this stack demonstrates that SpaceX continues toward being fully prepared to go on time or at least whenever that approval comes in. At the time of this recording, we are a few hours away from a SpaceX presentation on Starship. We’ll be bringing you those updates next week. For now, here’s a video.

One of the more unusual press releases this week came from SpaceX, providing an update on the Starlink 4-7 launch which we covered last week. It turns out that a geomagnetic storm that produced an impressive aurora visible in the northern U.S. also puffed up the Earth’s atmosphere to the point where up to 40 of the 49 satellites launched last week will decay from orbit uncontrollably.

The solar storm heated up the atmosphere. When you heat things up, they move apart, so the satellites at a higher altitude experienced more drag than usual from the extra air molecules. SpaceX controllers turned the satellites into safe mode, a configuration that reduces drag as much as possible. Unfortunately, the drag was too much, and some of the satellites were not able to come out of safe mode and begin to raise their orbits. So instead, they will decay from orbit in the next few days.

Starlink satellites are launched into a low 210×340-kilometer orbit for checkouts before they are raised to the operational orbits at 550 kilometers altitude. This approach helps clear the low Earth orbit of defective satellites quickly, as a non-zero number of Starlinks have been dead on orbital insertion. According to statistics kept by Jonathan McDowell, 201 Starlinks have been deorbited or decayed uncontrollably since the first launch in 2019. That’s over three entire launches’ worth of satellites lost to various defects. Even if the propulsion system checks out, the communications payload may not be functional, so the satellite will be deorbited.

Fortunately, the low orbit also means that the satellites have very little risk of colliding with any other satellites on their way back down into the atmosphere, and the satellites are designed to burn up completely in the atmosphere. This is an example of good orbital stewardship by the Starlink project, but they’re by no means perfect.

Back in 2019, during the early stages of the satellites’ deployment, ESA’s Aeolus weather satellite had to fire its thrusters to avoid a collision with a Starlink satellite that SpaceX didn’t move. The International Space Station has had to maneuver out of the way at least once because of close passes of the tension rods used to hold the satellites on the second stage. More recently, the Chinese space station Tianhe had to perform two avoidance maneuvers in 2021, in July and October, to avoid being hit by Starlink satellites. This resulted in a formal complaint to the United Nations.

Overall, this is a massive W for the Sun in the fight against mega-constellations! Nature is healing. Or something like that.

This problem will become even more of an issue as the Sun gets more active; we’re just getting out of the lowest part of the solar cycle, and it’s only gonna get worse. If this keeps happening, we may need to coin a new term for an artificial meteor shower when large numbers of failed Starlinks reenter in a short period.

The increased solar activity may also impact a new satellite being developed by a consortium in Singapore. Nanyang Technological University and others plan to launch a 100-kilogram microsatellite to a 250-kilometer orbit, or Very Low Earth Orbit. The satellite will be able to obtain a much higher resolution for its imaging system than satellites in a higher orbit but at the expense of needing more propulsion. Another investigation on the satellite will gather data on spacecraft charging, a problem where spacecraft essentially get static electricity on their surfaces, damaging them. The satellite will use an ion engine constantly providing a small amount of thrust to stay in orbit. Once its mission is complete, the engine will be turned off, and the satellite will decay in days, not leaving any debris in orbit.

From one unexpected failure in the present, we go to a fairly successful mission in the past in This Week In Rocket History.

This Week in Rocket History

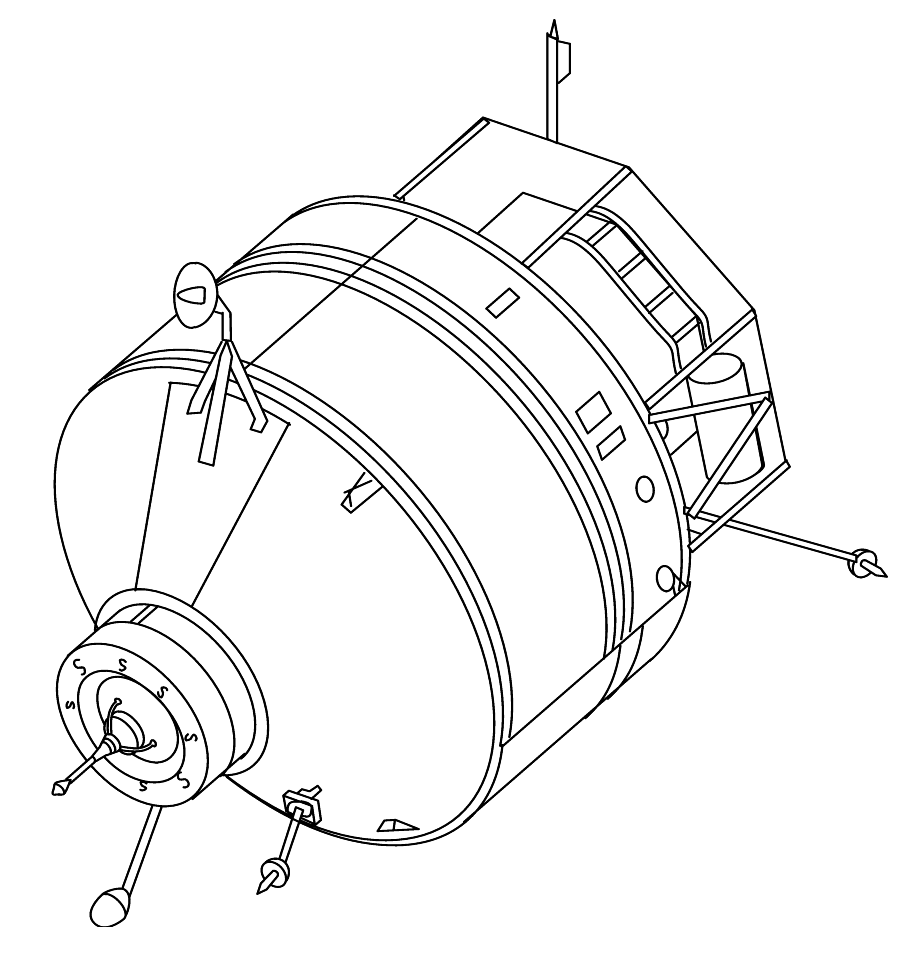

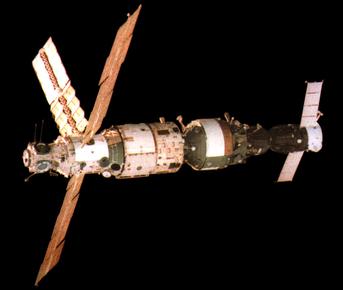

This week in rocket history is the launch of the first long-duration expedition to Mir, Soyuz TM-2, in 1987.

Soyuz TM-2 was the first crewed flight of the new Soyuz TM spacecraft, which incorporated a new rendezvous system, the Kurs, and a 250-kilogram payload increase due to lighter parachutes, along with a more powerful variant of the Soyuz launch vehicle which used higher impulse fuel.

The Mir space station was launched the previous year, 1986, but a crew had yet to spend any appreciable amount of time onboard. Mir was crewed for only two short stints: one of 55 days and the other twenty days during the Soyuz T-15 mission to Mir and Salyut 7. The crew of Soyuz TM-2 would end up spending almost a year continuously in space by the end of their EO-2 mission. However, there would be problems halfway through the mission, and only one crew member stayed onboard for that duration.

Soyuz TM-2 launched on February 5, 1987, taking the then-standard two days to rendezvous and dock with Mir. The crew of TM-2 was spaceflight veteran Yuri Romanenko on his third and final spaceflight and Aleksandr Laveykin on his first and only mission.

The first task for the crew was to unload Progress 27, an uncrewed resupply spacecraft that had docked with Mir two weeks earlier. Progress 27 was followed in March 1987 by Progress 28, which the crew also unloaded and packed with trash to be burnt up in the atmosphere.

These two resupply spacecraft completed the reactivation of the station and prepared it for the arrival of the second major module of the Mir station, Kvant, later renamed Kvant-1.

The docking of the Kvant module was dramatic. The first attempt on April 5 was called off after the rendezvous radar failed 200 meters out, and the module and its orbital tug barely missed hitting the station. Ground controllers regained control of the module, and it docked with Mir on April 9. However, the docking port didn’t achieve a hard dock, which was a problem.

The engineers decided to have Romanenko and Laveykin do an EVA to see if there was something stuck in the docking port. It turned out there was — a trash bag that the cosmonauts left behind when they were reloading Progress 28. It was stuck in the docking port. The cosmonauts removed the trash bag, and Kvant successfully latched.

The purpose of the Kvant module was to add astrophysics and materials science capabilities to Mir with several telescopes and forty cubic meters of pressurized space. To accurately point the astrophysics instruments at space, the Kvant module needed to control the entire station’s attitude and do it without thrusters. The cosmonauts tested this capability in late April 1987.

One of the telescopes studied supernova 1987A in June 1987. SN 1987A was the closest supernova to earth in almost 400 years and helped scientists determine the nature of the radiation in supernovas. Also in June, the two cosmonauts did a series of spacewalks to install two solar panels on the Mir core module.

In July 1987, Soyuz TM-3, the crew of which included the first, and so far only, Syrian astronaut to go to space, Muhammed Faris, relieved the crew of TM-2. They worked alongside each other for several weeks before returning to Earth with the visiting crew from TM-3 and Aleksandr Laveykin, who returned to Earth early because of a medical issue. They returned in the TM-2 spacecraft, leaving the TM-3 capsule in space. Laveykin was replaced for the remainder of the TM-2 expedition with Alexandr Aleksandrov from TM-3.

The two continued the important work of Mir Expedition 2, receiving Progresses 31 through 33 and discovering the first X-rays from SN 1987a in August 1987. In November 1987, a new relay satellite was launched to replace one that failed shortly before Soyuz TM-2 went to Mir. It allowed mission control to contact the station for more of each orbit.

Soyuz TM-4 arrived in December 1987, bringing Mir EO-2 to a close after 326 days, a new duration record.

And Aleksandr Laveykin, the cosmonaut who had to return to Earth early? He was just fine — only a small heart problem. He’s still alive, but he never flew in space again.

Statistics

And now, for some statistics.

The number of toilets in space is still eight, four on the ISS, one on the Soyuz, one on the Crew Dragon, one on Shenzhou 13, and one on Tianhe.

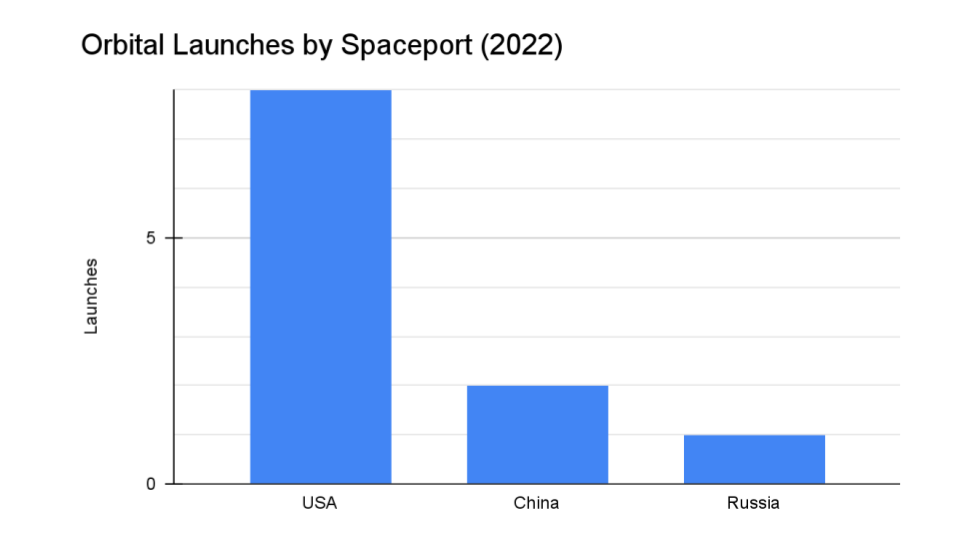

We keep track of orbital launches by launch site, also called spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA 8

China 2

Russia 1

From those eleven launches, a total of 266 spacecraft were put into orbit.

Your random space fact for this week is there have been three pairs of second-generation space travelers: Alexandr Volkov and his son Sergei Volkov, Yuri Romanenko and his son Roman Romanenko, and finally, Owen Garriot and his son Richard Garriot.

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.