Using a machine learning algorithm, scientists have confirmed 68 out of 77 potential gravitational lens candidates from a subset of over 5,000 possibilities. Plus, generation one stars, astronauts coming home, dating craters on Earth, lunar glass, and an interview with Amanda Sickafoose regarding the DART mission.

Podcast

Show Notes

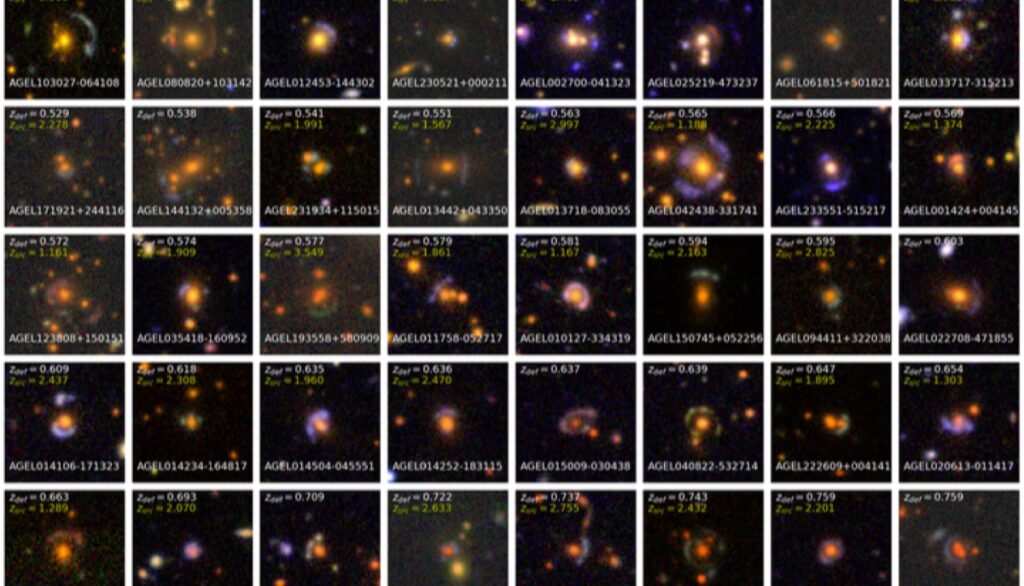

Confirmed: 68 new gravitational lenses

- Science in Public press release

- “The AGEL Survey: Spectroscopic Confirmation of Strong Gravitational Lenses in the DES and DECaLS Fields Selected Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” Kim-Vy H. Tran et al., 2022 September 26, The Astronomical Journal

Found: Debris of first stars

- NOIRLab press release

- “Potential Signature of Population III Pair-instability Supernova Ejecta in the BLR Gas of the Most Distant Quasar at z = 7.54,” Yuzuru Yoshii et al., 2022 September 28, The Astrophysical Journal

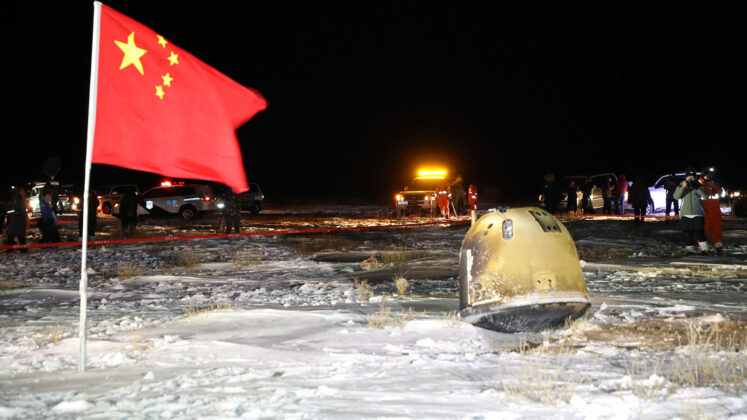

Soyuz MS-22 returns to Earth

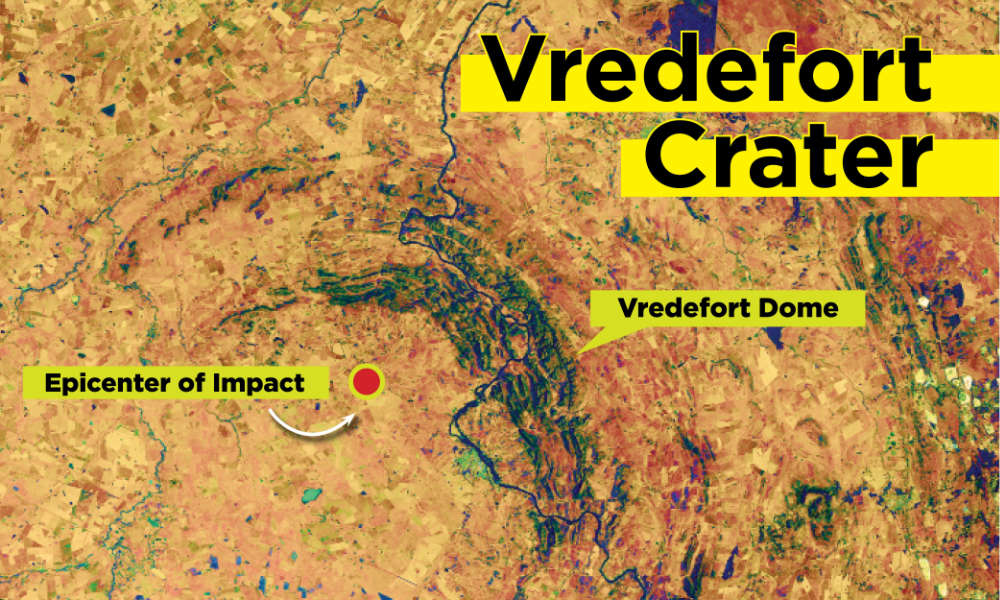

Vredefort crater much larger than originally thought

- University of Rochester press release

- “A Revision of the Formation Conditions of the Vredefort Crater,” Natalie H. Allen et al., August 2022 8, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets

Lunar glass reveals matching impacts with Earth

- Curtin University press release

- “Constraining the formation and transport of lunar impact glasses using the ages and chemical compositions of Chang’e-5 glass beads,” Tao Long et al., 2022 September 28, Science Advances

Transcript

DART has dominated the news cycle this week, and today is not any different for us. We’ll have an interview with Amanda Sickafoose about her observations of the spacecraft’s impact from the South Africa Astronomical Observatory later on in the show. We’re also going to cover a couple of stories that relate to just why this mission is important… asteroid impacts and all that.

We’re also going to talk about how accurate a new machine learning algorithm is at finding gravitational lenses and how a quasar has helped uncover evidence of a gen one star. Oh, and some astronauts returned to Earth.

All this and more today, here on the Daily Space.

Pamela is still battling her injury, so I am your host, Beth Johnson.

And we are here to put science in your brains.

Today’s top story is the publication of 68 confirmed gravitational lenses from a subset of 77 candidates drawn from a list of 5,000 candidates found in the Dark Energy Survey and Dark Energy Camera Legacy Survey by neural networks. This represents an 88% success rate.

These lenses use gravity to bend light toward us that would normally travel to other parts of the universe, thus magnifying what we see. Since galaxies are lumpy but gathered into roundish clusters, these magnified galaxies appear as distorted arcs. This work is published in The Astronomical Journal with lead author Kim-Vy Tran. She explains: Our goal with AGEL is to spectroscopically confirm around 100 strong gravitational lenses that can be observed from both the Northern and Southern hemispheres throughout the year.

Since telescopes are unevenly distributed around the world, this kind of positioning allows for continuous observations.

Galaxies can be lensed multiple times, and any flicker that can be observed in multiple lenses can tell us about the light path of each lensed galaxy… and about the changing geometry of our universe.

Here is to hoping this team has clear skies and time on big scopes to see this project succeed.

I’m not sure I actually have the language to express how exciting this next story is, but I’m going to try. According to Carl Sagan: If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.

Well, one of the early steps in making that universe is making stars. We have been searching for evidence of those first stars from the moment we realized our universe had a time=0. And we have been failing to find them for about a century.

That changes today. A team led by Yuzuru Yoshii has identified a supernova remnant that is chemically consistent with its forming when a 150–300 solar mass star exploded. That first generation star was made with only the atoms made during the Big Bang.

This nebula’s gas was found in the outskirts of a distant bright galaxy. The light we are seeing comes from when the universe was less than a billion years old. And what we see so far matches the models we hoped were right.

This is just one object, but it shows us, finally, that these things can be found, and now, I’m sure, this team and others will be looking for more.

While we wait, let’s turn to Eric with astronauts coming home.

Late Wednesday night, the crew of Soyuz MS-21 packed up their spacecraft and undocked from the International Space Station (ISS) after a several-hour-long leak check. The moment of undocking marked the beginning of ISS Expedition 68, commanded by ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti.

After several more hours coasting away from the ISS – because you really don’t want to fire a rocket engine near the station – the Soyuz conducted its deorbit burn. This burn lasted for five minutes, after which Soyuz separated its Orbital and Service modules and oriented for reentry.

One hour later, the capsule landed on the cold steppe of Kazakhstan, a few hundred kilometers from the town of Zhezkazgan. All Soyuz capsules and other Soviet/Russian recoverable capsules have landed in this area.

The all-Russian crew of Soyuz MS-21 returns after 195 days in space. Two of the members completed their first flight into space, and the last, Oleg Artemyev completed his third. Artemyev and cosmonaut Denis Mateev conducted several spacewalks together to prepare the European Robotic Arm on the Nauka module for operations, with Artemyev doing 33 hours across five spacewalks and Mateev 26 hours across four. Sergei Korsakov did not perform any spacewalks during the mission.

With this successful landing, there are again eight toilets and seven humans in space, though it will be back to nine again shortly once SpaceX Crew 5 launches. That launch was expected on October 3 but has been delayed as KSC is experiencing the impacts of Hurricane Ian. The Falcon 9 rocket and Crew Dragon capsule for that mission are both safely inside the Horizontal Integration Facility at 39A, which is built to survive the expected conditions.

And now, back to the science.

When we talk about planetary defense, especially in the context of the DART mission, mass extinction events – such as the Chicxulub impact – tend to come up in conversation. That particular event involved an impactor about ten kilometers in diameter which left a crater 180 kilometers across. Not only did the dinosaurs die off, other global effects included atmospheric heating, forest fires, acid rain… basically global devastation. Hence the importance of the DART mission.

It’s easy to focus on that one single event as being a reason to work toward planetary defense, but Chicxulub was by far not the only impact or even the largest. That designation goes to the Vredefort crater in South Africa, which up until recently, was thought to have been formed by an object measuring 15 kilometers in diameter. Now, in a new paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets and led by Natalie Allen, computer simulations based on new geological evidence have upped that estimate to between 20 and 25 kilometers.

Estimating the size of the original crater and therefore the size of the impactor is a difficult process due to the erosive properties of our planet. The crater is two billion years old, and that is a lot of erosion to account for. The new evidence supports an original size of 250 to 280 kilometers, and the simulations show that the object had to have been traveling at 15 to 20 kilometers per second to leave such a huge crater.

Upon impact, dust and aerosols would have spread in the atmosphere, blocking sunlight. As for what was living on Earth at that time, co-author Miki Nakajima explains: Unlike the Chicxulub impact, the Vredefort impact did not leave a record of mass extinction or forest fires given that there were only single-cell lifeforms and no trees existed two billion years ago; however, the impact would have affected the global climate potentially more extensively than the Chicxulub impact did.

On top of there not being a lot of biological evidence of the Vredefort impact, the locations of landmasses two billion years ago would have been vastly different. Error bars on just what that looked like get larger the farther back in geologic time simulations go, but this new research could provide a better understanding of the makeup of the ejecta and how far it might have traveled after the initial impact. Finding that ejecta around the world would make it easier to create a more precise picture of the Earth at the time.

Once again, we remind you that there are presently no known asteroids greater than 140 meters in size that are known to be a threat to Earth for at least 100 years. All of the research into craters and asteroids helps us understand the potential threats that are out there and what effects they could have on our world.

Research into impact events doesn’t only involve craters here on Earth. A new study in Science Advances analyzed lunar glass brought back by the Chang’e-5 sample return mission and found that what we thought were just major events on Earth were actually accompanied by smaller impacts on the Moon.

Researchers studied the glass beads, which were up to two billion years old (sound familiar?), using a variety of techniques including microscopic analysis, numerical models, and geological surveys. Lead author Alexander Nemchin notes: We found that some of the age groups of the lunar glass beads coincide precisely with the ages of some of the largest terrestrial impact crater events, including the Chicxulub impact crater responsible for the dinosaur extinction event. The study also found that large impact events on Earth such as the Chicxulub crater 66 million years ago could have been accompanied by a number of smaller impacts. If this is correct, it suggests that the age-frequency distributions of impacts on the Moon might provide valuable information about the impacts on the Earth or inner solar system.

Next up, the team wants to compare the Chang’e-5 data with other lunar soil samples and crater ages. Maybe we can even further constrain when the Vredefort impact event occurred.

Coming up next, my prerecorded interview with scientist Amanda Sickafoose about the DART impact and the images collected in South Africa. It all ties together today!

Interview

On Monday, September 26, at 23:14 UTC, in front of a global audience, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test successfully hit the tiny, 160-meter asteroid Dimorphos. Numerous telescopes around the world and in space, including the South African Astronomical Observatory, all had their instruments turned toward the collision. Joining us today is Amanda Sickafoose, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute who was conducting the observations at the SAAO.

Thank you for joining us today, Amanda.

Once again, thank you for being here today. Good luck with the occultation!

This has been the Daily Space.

To all of you watching, our prerecorded interview ran longer than we can air here on NowMedia. You can catch the conversation in its entirety on our website, DailySpace.org.

While you’re there, check out our show notes to find more information on all our stories, including images. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Annie Wilson, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, and Gordon Dewis

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.