After ten months of space travel, NASA’s DART spacecraft arrived at the asteroid Didymos, targeted the moonlet Dimorphos, and successfully flung itself at the surface. Multiple observations confirm that the system brightened and even managed to resolve a cloud of debris. Plus, rocket launches, an update on the SLS, some broken physics, and International Observe the Moon Night.

Podcast

Show Notes

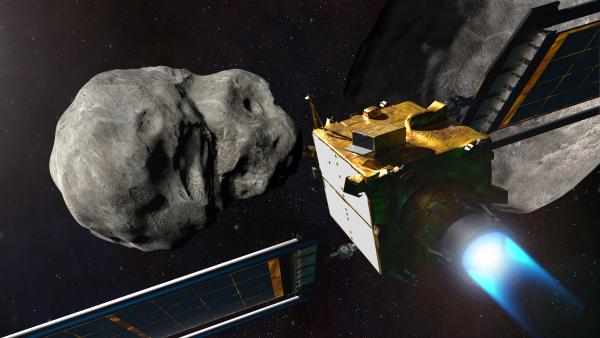

DART mission successfully boops Dimorphos

- DART’s Small Satellite Companion Tests Camera Prior to Dimorphos Impact (NASA)

- ESA to capture light from deflected asteroid’s new plume (ESA)

- DLR press release

- NASA press release

- PSI press release

NASA Launches… Balloons?

- NASA press release

Last west coast Delta 4 heavy launches classified payload

- ULA press release

Starlink 62 sets a pad turnaround record

- Starlink mission page (SpaceX)

SLS rolls back to VAB

- NASA to Roll Artemis I Rocket and Spacecraft Back to VAB Tonight (NASA Blogs)

- NASA’s Moon Rocket and Spacecraft Arrive at Vehicle Assembly Building (NASA Blogs)

- Assessment Underway on Electrical System in Vehicle Assembly Building (NASA Blogs)

56,000 galaxies tell astronomy to check its math

- UH Manoa press release

- “Cosmicflows-4,” R. Brent Tully et al., accepted to The Astronomical Journal (preprint)

Hubble still brings beautiful science images of young star

- NASA Goddard image release

What’s Up: Week of 9/26/22

- NASA press release

- Weird Ways to Observe the Moon (NASA JPL)

Transcript

One of the goals of this show is to bring you the top stories in space science and all the rocket news we can. This week, Pamela wrote in our show run: rockets, more rockets… and then just gave up on naming all the things leaving our planet and leaving us behind for now, but you never know what life can bring.

And today, along with oh so many rockets, we also bring you news of the DART mission’s purposeful collision into an asteroid’s moon, some broken physics, and even a gorgeous Hubble image and round-up of what you see in the sky.

All this and more, here on the Daily Space.

Pamela is out with a minor injury, so today I’ll be your host, Beth Johnson.

And we are here to put science in your brains.

Congratulations to the DART mission teams! On Monday, September 26, at 23:14 UTC, in front of a global audience, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test successfully hit the tiny, 160-meter asteroid Dimorphos. Images streamed in from the onboard camera, DRACO, as the spacecraft approached the rocky surface, ending with a barely started image before going dark. But what a set of images they were up until then.

When the feed first went live, DART was still focused on Didymos, the larger of the binary asteroids, also referred to as the primary, as the spacecraft could not yet resolve the two bodies separately. Then, around T minus one hour, the autonomous system, or SMART Nav, needed to detect Didymoon, begin tracking the satellite, and lock onto it. During the SETI Institute’s live stream, DART Lead Investigator Andy Cheng announced that the spacecraft had achieved all of those goals and was on approach to the target. Moments later, Dimorphos was finally resolvable in the DRACO live feed.

Over the next 45 minutes, features on both Didymos and Dimorphos began to come into view, revealing that the pair are mostly like rubble pile asteroids similar to Ryugu and community favorite, Bennu. Boulders and craters and even a few flatter areas were clearly visible, and we expect that the images will be heavily analyzed over the coming weeks.

Due to the slight delay between sending the images and receiving them, about the scheduled time of the impact, Dimorphos began to fill the camera, eventually ending with that previously mentioned barely begun image. The spacecraft successfully hit the target, and everyone watching cheered to see it.

This mission was the first-ever planetary defense test, and NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said: At its core, DART represents an unprecedented success for planetary defense, but it is also a mission of unity with a real benefit for all humanity. As NASA studies the cosmos and our home planet, we’re also working to protect that home, and this international collaboration turned science fiction into science fact, demonstrating one way to protect Earth.

Of course, the day’s activities did not stop there. Numerous telescopes around the world and in space, including ATLAS, ALMA Observatory, Hubble Space Telescope, and a network of amateur astronomers, all had their instruments turned toward the collision. Within a few hours, ATLAS posted on social media a gif of the Didymos system brightening and visibly ejecting a cloud of debris, confirming the impact.

One of the events we were waiting for is visual confirmation and images from DART’s companion CubeSat, LICIACube, provided by the Italian Space Agency. LICIACube was released from DART fifteen days ago and only carries a tiny antenna, so the images will have to be downlinked one by one over the next few weeks, and the first two of those images were shared late Monday night. Between the CubeSat and the other telescopes tuning in, scientists will have a wealth of information to analyze, including answering the question: Did we actually change the orbit of Dimorphos?

We will bring you the answer here on Daily Space as soon as NASA announces the result.

One last note, as we mentioned last week, in 2024, the European Space Agency plans to launch Hera, a spacecraft that will arrive in 2026 at the Didymos system, and take observations of both asteroids. Hera will be in the company of two CubeSats to take a complete survey, focusing especially on the impact crater left behind… because after this week, we suspect that there is an impact crater to observe.

We’ll have links to all the images released so far in our show notes at DailySpace.org.

Coming up next, Erik brings us all the rocket launches from the past few days as well as an update on the SLS and its troubles.

Earlier this month, NASA Wallops managed the launch and operations of six stratospheric balloons from New Mexico. Four of them have now been successfully recovered. One of them, BALoon Based Observations for sunlit Aurora or BALBOA, studied aurorae during the day. That particular balloon was launched and recovered on September 7.

The next day, on September 8, a balloon called High Altitude Student Platform 16 launched carrying twelve small payloads and then landed on September 9.

The TinManHand experiment was not exactly space-related but was instead studying the effects of upper atmospheric charged particles on aircraft avionics. This flight was a little sporty. The balloon launched on September 23, and the payload descended the same evening; however, a problem with its recovery parachute occurred, and the payload smashed into the ground under a fouled parachute. No one on the ground was injured. The balloon remained in the air until September 26. It has not been found. According to the Federal Aviation Administration, the lost balloon did not interfere with any other objects in the air.

The remainder of the balloons will be launched through October.

And as usual, we have rocket launches.

First, a milestone: the final United Launch Alliance Delta 4 Heavy took off from SLC-6 at Vandenberg Space Force Base on September 24.

This mission carried a classified satellite into orbit for the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) inside the rocket’s massive fairing. No details were disclosed about its purpose, and as usual, the webcast coverage ended just after fairing separation at the NRO’s request. Since they can’t exactly hide the launch itself, they do this instead.

The Delta 4, and the Heavy variant, in particular, has a decades-long history of ground equipment problems related to its liquid hydrogen propellant and typically goes through several attempts before finally launching.

This time, however, the Delta 4 Heavy carrying NROL-91 lifted off on its first attempt after teams resolved a few small problems.

The RS-68 engine startup sequence involves dumping large amounts of hydrogen out of the engine which, on ignition, causes a fireball up the rocket that chars the insulation. While alarming if you’re not expecting it, this fireball is, in fact, completely normal. Over the years, the startup sequence of the three engines has been refined to make this fireball smaller, but it is still visually striking… and also something we won’t see many more times in the future.

Sometime after launch, ULA officially confirmed mission success on their website and social media. The payload was given the name USA 338 in online satellite catalogs, though, of course, its orbit was not listed.

And of course, there was yet another Starlink launch, this one only an hour after NROL-91 on the opposite side of the country from SLC-40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. It featured a relatively new Falcon 9, booster 1073, which successfully launched and landed for the fourth time. To date, B1073 has launched one paying customer and three Starlink missions. One notable item about this flight is that it marked the fastest turnaround time of a launch pad in SpaceX’s history, just short of six days.

There were also three launches from China on Saturday and Sunday, delivering a total of eight satellites into orbit, about which we know little. One launch was conducted by a Long March 2D, another by a Kuaizhou-1A, and the last by a Long March 6.

After a weekend of back and forth, including a point where NASA deputy associate administrator Tom Whitmeyer said it “wasn’t even a named storm”, NASA has finally made the decision to roll the Space Launch System rocket back into the Vehicle Assembly Building to ride out Hurricane Ian, which became a major hurricane according to the National Hurricane Center sometime Monday night or early Tuesday. The risk with this delay was that the rocket can handle more winds while at the pad than it can while moving, so if it got caught in the storm due to a delayed rollback decision, the SLS could have sustained significant damage.

This rollback also gives NASA the opportunity to remove and replace the Flight Termination System (FTS) batteries, bringing them back in compliance with requirements from the Eastern Range for operating with the legacy system. Modern rockets such as the Falcon 9 put the vehicle’s own flight computer in charge of making the decision to blow up in the event of a problem, while all other rockets require a human to make the decision. The FTS has its own separate batteries and transmitters independent of the rocket to ensure the capability is ready when needed.

Rollback was completed the morning of September 27, heralded by a small fire in an electrical panel on the VAB. No one was injured, and the SLS was not damaged.

Unfortunately, this rollback means the launch attempts for October are off the table. At least NASA won’t ruin Halloween, though this does increase the chances of a major NASA event ruining two Christmases in a row. Thanks, NASA.

After Erik’s story, I feel the need to point out that DART did its thing on Rosh Hashanah. Anyway…

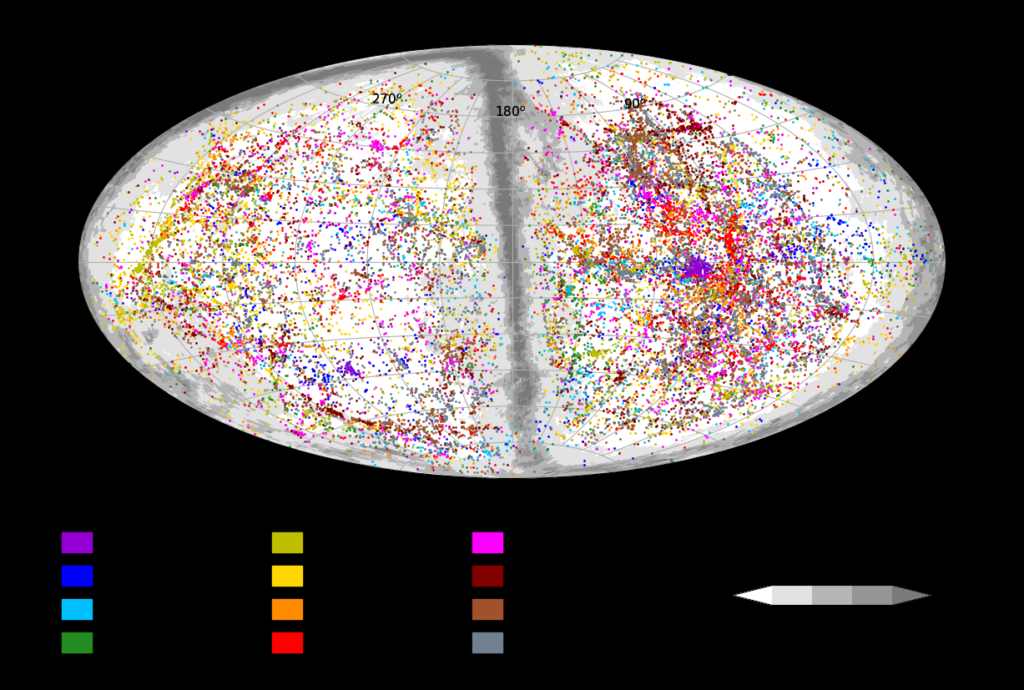

A new paper is coming out in The Astronomical Journal that looks at 55,877 galaxies that were imaged during a variety of different surveys, putting together all the data to try and understand the expansion of the universe.

This work is led by Brent Tully, a researcher who co-discovered with Richard Fisher in the 1970s that some kinds of galaxies have a correlation between their rotation rate and luminosity. This means that if you measure a galaxy’s rotation rate and how bright it appears you can use your knowledge of its luminosity to calculate its distance. In the intervening 40+ years, relationships between galaxy structures and luminosity have been detailed.

In this new paper, they use these relationships to measure distances instead of the more common techniques of looking at supernovae, variable stars, and other current or former stellar objects.

Combining these results with measurements of the galaxies’ velocities, they measured the expansion of the universe… And they got a number wildly different from everyone else: 75 km/s/Megaparsec.

Teams using current and former stellar objects like supernovae get 73 km/s/Mpc, and folks using the cosmic microwave background get 67.5 km/s/Mpc. The error bars on all these measurements are smaller than the separation of these values.

Somewhere in the maths or in the measurements or in both, there is a problem in our understanding of the evolution of our universe. It could be as simple as each project having a bad zero point, like a ruler with the first couple millimeters worn off, or there is just a difference in the scaling, like a set of photocopied tape measures that are accidentally zoomed in different amounts.

The smartest astronomers in the world are trying to sort these discrepancies, and we here at the Daily Space will bring you their progress as we take steps forward, and sometimes backward, in our understanding of the universe.

For now, though, let’s take in a pretty picture, and later in Erik returns with this week’s “What’s Up.”

Just like a meme, a whole lot of folks have turned away from their steady bae, the Hubble Space Telescope, to stare open-mouthed at JWST.

Please stop it.

We still have Hubble doing amazing work, and the team recently put out a new image release of the young star, IRAS 05506+2414.

This star is forming in the direction of the constellation Taurus. By taking a series of images over time, researchers were able to see motion in the fanning outflow of material. It’s actually super weird to see fans rather than nice narrow jets, and researchers think this may be an example of a massive young star experiencing some kind of disruptive explosive event.

These fans are now moving at 217 miles per second, and I hope that Hubble keeps working for a few more years so it can keep documenting this system’s expansion in gorgeous images.

Sadly, this isn’t an object your backyard telescope can even catch a glimpse of. Don’t worry though: up next, Erik brings you some things you can focus on.

What’s Up

This week in What’s Up are a few more events you should be on the lookout for in the next month.

First off, the Moon will be in the first quarter next week on October 3, which along with the third quarter, is the best time to observe the Moon’s features because the angle of the Sun provides the most contrast on the surface. You can tease out fine details easier this way.

Just before the formal first quarter is this year’s International Observe The Moon Night on Saturday, October 1. This is the twelfth edition of this event, which features public star parties all around the world dedicated to observing the Moon. As of press time, there were over 800 events scheduled. You can find more information on local events at the link in our show notes on DailySpace.org.

Of course, you don’t need to go to one of these to view the Moon; you can do it by yourself. Simply go outside and look up. Binoculars or a small telescope will help you tease out some of those details.

Next up, Mercury will make its next greatest western elongation on October 8. This is one end of the furthest angular separation it gets from the Sun, which still isn’t far as Mercury orbits so close. The western elongation is the best time to see Mercury just before sunrise in the Northern Hemisphere.

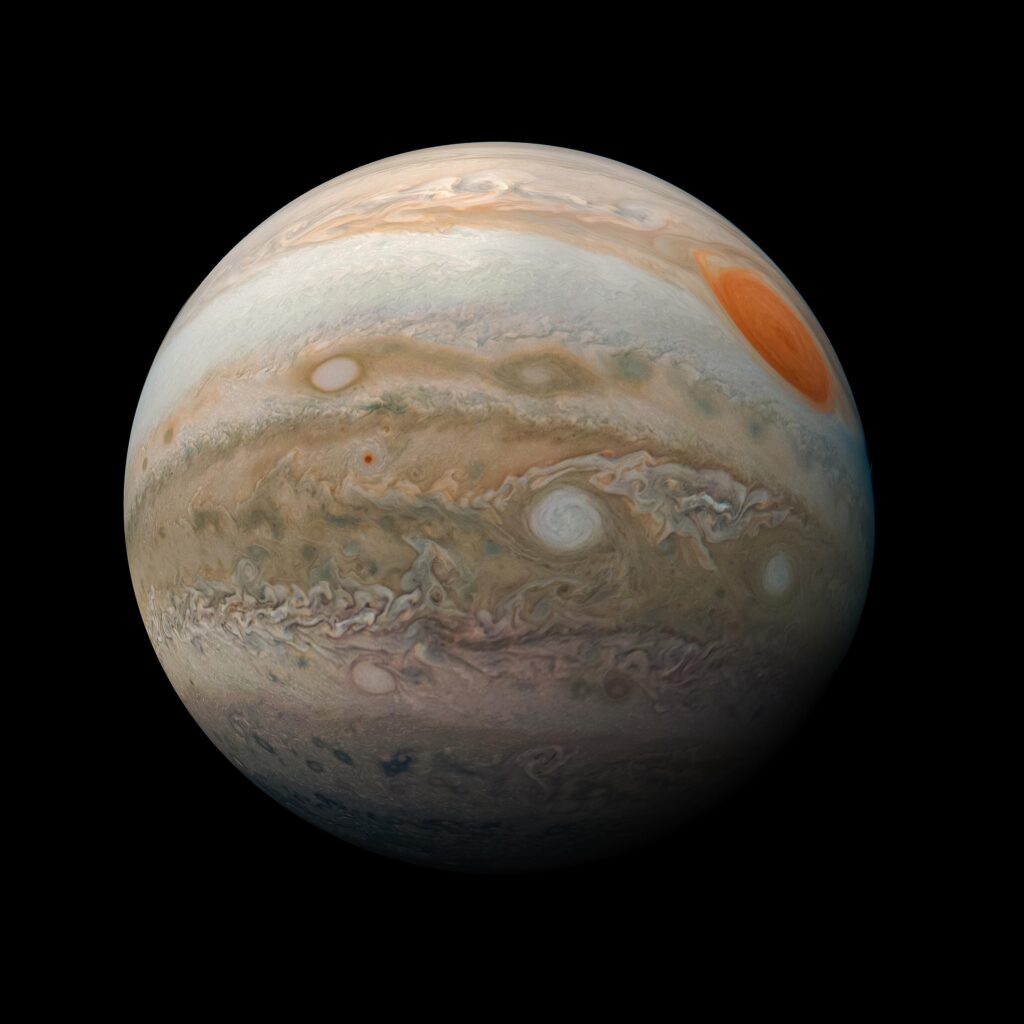

Finally, later in October, there will be a rare phenomenon that will actually take place three times: a double moon transit on Jupiter. While Jupiter has 80 moons that we know about, the four Galilean moons – Europa, Callisto, Io, and Ganymede – pass in front of the disc of Jupiter fairly often, and you can usually see their shadows on Jupiter as they’re crossing. Most of the time, you only get one shadow at a time and maybe a second right after the first one finishes its transit; it’s quite rare to have two moons transiting at the same time… let alone three of these events over the course of a couple of weeks.

The first of these double transits is on October 12, the second on October 19, and the last on October 25. Be sure to catch Jupiter before it heads below the horizon for the winter.

For now, though, this has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Annie Wilson, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, and Gordon Dewis

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.