The second stage of a Falcon 9 rocket launched in 2017 re-entered the atmosphere over Mexico, breaking up and creating a show of fiery lights in the sky. Plus, dead stars with possibly living planets, more on moon formation, more launches, more launch failures, and a review of “The Apollo Murders” by Chris Hadfield.

Podcast

Show Notes

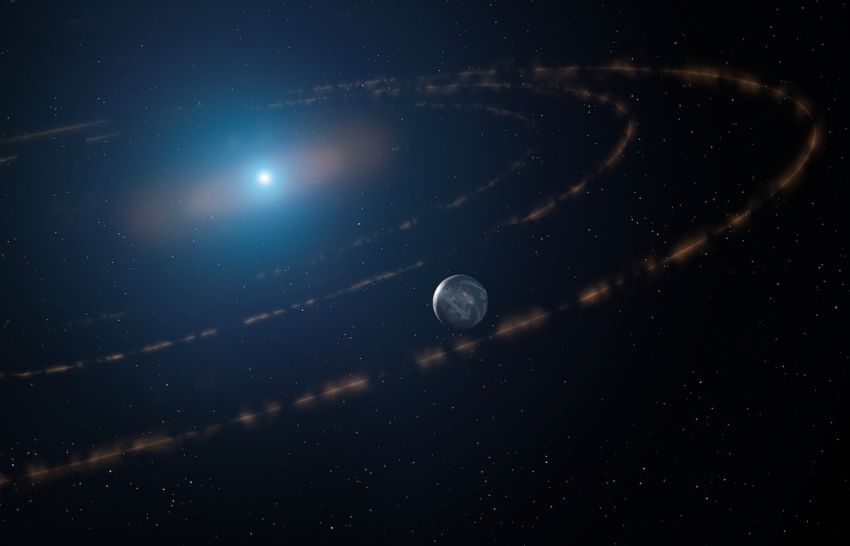

Dead stars could support new life

- Royal Astronomical Society press release

- University College London press release

- “Relentless and complex transits from a planetesimal debris disc,” J Farihi et al., 2022 February 8, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

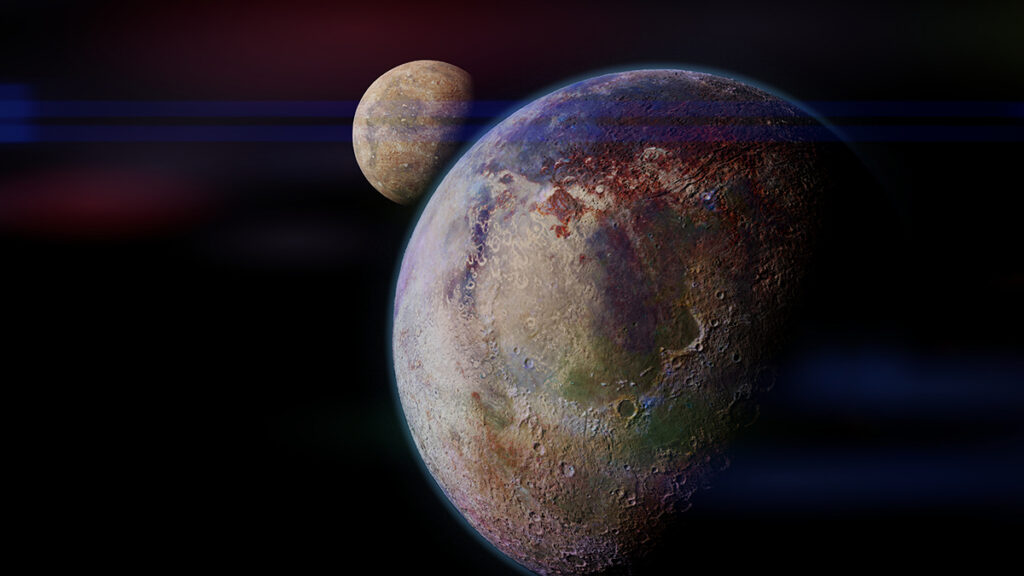

To make a big moon, start with a small planet

- To Make a Big Moon, Start with a Small Planet (Eos)

- “Large planets may not form fractionally large moons,” Miki Nakajima, Hidenori Genda, Erik Asphaug, and Shigeru Ida, 2022 February 1, Nature Communications

Ryugu sample matches Ryugu

- *Free* Samples brought back from the asteroid Ryugu match its surface and sub-surface (EurekAlert)

- “Pebbles and sand on asteroid (162173) Ryugu: In situ observation and particles returned to Earth,” S. Tachibana et al., 2022 February 10, Science

JWST to start collecting data

Soyuz launches more OneWeb satellites

- OneWeb press release

Astra Rocket 3.3 fails to orbit NASA satellites

- We Have Liftoff! ELaNa 41 Mission Rockets to Space (NASA)

- ELaNa 41 Mission Update (NASA)

- ELaNa 41 mission page (NASA)

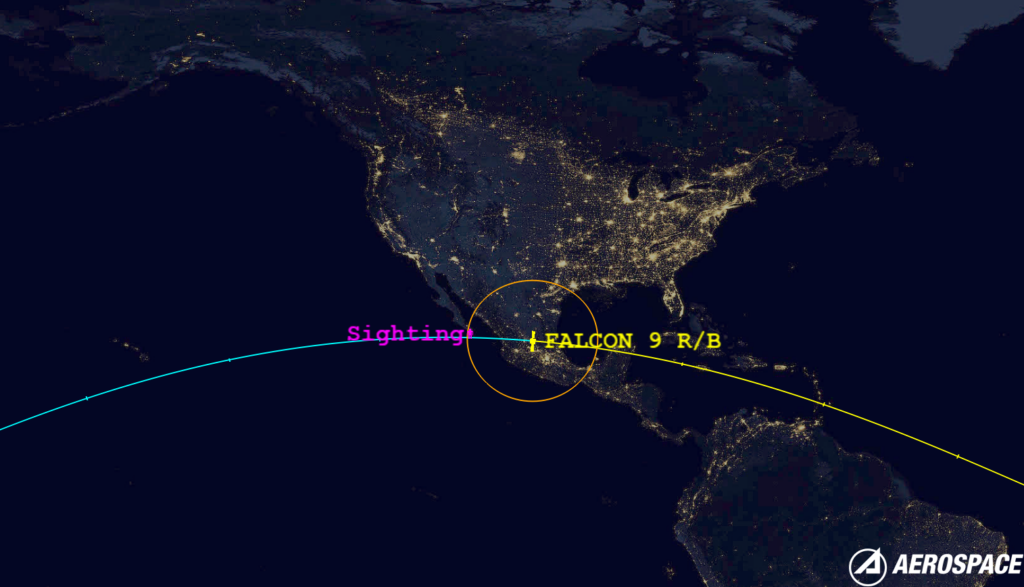

Old Falcon 9 stage reenters over Mexico

Starship updates with stacked backdrop

Review: The Apollo Murders by Chris Hadfield

- The Apollo Murders (Amazon)

Transcript

We seem to have survived another week in this weird landscape of a timeline where everything is on fire, but we continue to bring you the latest in space news. And today, we’ve got dead stars making new planets, how to make a big moon, initial results on the sample from asteroid Ryugu, and an actual image from JWST.

Plus, we’ll be bringing you so much rocket news, it needed an entire section of the show. And last but not least, Beth and Erik are going to review astronaut Chris Hadfield’s first fiction novel.

All of this now, right here on the Daily Space.

I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay.

And I am your host Beth Johnson.

And we’re here to put science in your brain.

There isn’t always a rhyme or reason to the way new research papers get published. Often, and entirely by coincidence, different papers will come out all at once that look at different aspects of the same problem, and when seen from an outside perspective, they paint an even more interesting picture than each paper can tell alone. In a recent episode, we brought you news of a white dwarf star – an ember of a star like our Sun that has died – and how that white dwarf was consuming one of its former planets.

Today, in a new paper in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers led by Jay Farihi published new research on a white dwarf star surrounded by debris that appears to be shaped by the presence of a planet — a planet that formed after the star had already died. This is a new planet, a post “the star was actively fusing and alive” planet.

Researchers looked at the white dwarf WD1054–226 found fluctuations in its light that indicate 65 evenly spaced clouds of material orbiting every 25 hours. Basically, the light acts like a chaotic dashed line is passing over it.

According to Farihi: An exciting possibility is that these bodies are kept in such an evenly-spaced orbital pattern because of the gravitational influence of a nearby major planet. Without this influence, friction and collisions would cause the structures to disperse, losing the precise regularity that is observed. A precedent for this ‘shepherding’ is the way the gravitational pull of moons around Neptune and Saturn helps to create stable ring structures orbiting these planets.

Farihi continues: The possibility of a major planet in the habitable zone is exciting and also unexpected; we were not looking for this. However, it is important to keep in mind that more evidence is necessary to confirm the presence of a planet.

These structures are in a part of this solar system that would have been inside the star when it was a red giant in the past. Now, this region is in the white dwarf’s habitable zone. Yes, dead stars have habitable zones. White dwarfs are the slowly cooling cores of stars, and they start out so hot that they blast light in ultraviolet. Over time, they cool, but that time is measured in billions of years, and they do have evolving habitable zones for all those billions of years.

In combination with the earlier paper, this tells a remarkable story of white dwarfs both eating planets and forming planets in a remarkable “out with the old and in with the new” kind of story. A white dwarf that isn’t consuming material is a steady star that produces a regular light and a not-too-horrible environment. That offers a new possibility for life to form someplace we just hadn’t been looking, and I now wait eagerly for a sci-fi writer to pick up this idea and run.

Science is a process, and just like the plots of so many soap operas, along the way we keep learning that what we thought was true is wrong and what is real is far more fantastical than we imagined and often.

It is a star steal planet, eat planet, make new planet kind of universe out there, folks. And in trying to understand how worlds like Earth and Pluto, with proportionally giant moons, can come into existence, the story has just started to get juicy.

In new research published in Nature Communications, researchers led by Miki Nakajima find that to get a moon that is a significant fraction of the size of the world it orbits, you need to start with a rocky world six times Earth’s size or smaller or an icy world the size of the Earth or smaller.

And once you have that world, you have it hit it with a giant impactor.

We never said the Universe was gentle.

In simulations, researchers collided worlds of various sizes, replicating the situations we see in our solar system while demonstrating what is and isn’t possible. According to a story by friend-of-the-show, Kim Cartier: ...simulations revealed that rocky planets heavier than 6 times Earth’s mass, equivalent to about 1.6 times the size of Earth, are unable to form a fractionally large moon out of the collision debris (but could still form much smaller moons). Icy planets heavier than 1 Earth mass or larger than about 1.3 Earth radii are equally unable to create large moons. Below those mass thresholds, the planets were able to create a moon at least a few percent of the planet’s mass.

This implies that we aren’t going to find a Neptune-sized world with an Endor orbiting it, but we may find more Earth-Moon-like combos that get born through the collision of two unsuspecting worlds that never meant to merge and start a family.

Soap opera, people. Science is just a wild soap opera.

We have two final news notes before we look at the past 24 hours of rocket mayhem.

First up, researchers have confirmed that the sample of material Hayabusa2 brought back from the surface of the asteroid Ryugu matches what was seen on the asteroid’s surface and in areas blasted to reveal the subsurface.

I have to admit, my first reaction to this paper was, “And water is wet.” If you send a spacecraft to an asteroid and grab stuff off its surface, of course, it’s going to match, but then I remembered that Apollo astronauts brought back a meteorite from the surface of the Moon.

So, water is wet, but sometimes we have to prove it because frozen water can be kind of dry. Or, in this case, sometimes bad luck happens, and we have to verify a sample is representative of the whole. And this is a long-winded way of saying that Hayabusa2’s 5-gram sample of Ryugu matches expectations and is representative of the world.

No soap opera plot twists for this asteroid. Not today.

And, in further news of no surprises are good, JWST has sent back a selfie showing its out-of-alignment mirrors. This is a first step toward doing science someday, many months in the future. NASA has stated that we should expect to start seeing images – bad-looking images – of stars as they work to align the mirrors and get the telescope sorted into a better configuration.

Pamela is going to continue to ignore this mission until the data looks good, out of fear that a watched telescope will never focus.

Next up, Erik Madaus brings us a round-up of the past 24 hours of rocket news, and it was a lot, folks.

Just in case you forgot there were other satellite internet constellations, on February 10 at 0609 UTC, an Arianespace Soyuz 2.1b/Fregat launched the OneWeb 13 mission from the Guiana Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Onboard were 34 satellites.

This launch increased the constellation to almost two-thirds complete, 428 of 650 satellites. Other launches have occurred from the Baikonur and Vostochny Cosmodromes, two of the other space centers the Soyuz launches from. OneWeb expects to finish the constellation later this year.

Also on February 10, at 20:00 UTC, an Astra Rocket 3.3 launched the ELaNA 41 mission from SLC-46 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. This was the second attempt to launch this mission, after a scrub at T-0 earlier in the week.

This attempt proceeded smoothly up through liftoff. The rocket lifted off and headed over the Atlantic Ocean. The first-stage burn was nominal, but the fairings did not separate properly, trapping the second stage in the rocket. It broke free after ignition but picked up a spin as a result. The second stage did not recover, so the mission was lost.

On an interesting note for the current age of commercial spaceflight, Astra is a publicly-traded company. As soon as the webcast showed the second stage malfunction, their stock price dropped significantly, to the point where trading was stopped for five minutes. Once trading resumed, it dropped even more until the market closed for the day. In total, it lost 26% of its value.

Needless to say, this is a big blow for Astra, who has had a single successful launch out of eight attempts. It’s also a blow for NASA, which contracted the launch through the Venture Class Launch System. The four payloads were from The University of Alabama, University of New Hampshire, University of California Berkeley, and NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

Also, this past weekend, people in Mexico noticed a bright streak moving across the sky and breaking into pieces. People all over Twitter thought it was an incoming meteor, but there are several important differences between a meteor and what it actually was – space debris.

Meteors move much faster than space debris, crossing the sky in seconds, and can come in any direction. Space debris typically moves slower, crossing the sky in minutes because it’s in Earth orbit, not coming in from a solar orbit. Also, except for very rare circumstances, all space debris will reenter going from west to east because that’s the direction almost all rockets launch.

The particular space object which made a bright return to Earth Saturday afternoon was the second stage from a Falcon 9 rocket that, in 2017, sent a satellite into super synchronous transfer orbit, a type of geostationary transfer orbit with the apogee far higher than geostationary altitude.

After satellite deployment, it was vented of all remaining propellant and battery chemistry and left to drift in orbit instead of being deorbited. This is the current industry practice. It spent the next five years slowly decaying through atmospheric drag. It was tracked since launch, and predictions on when it would reenter were made by the U.S. government for several days prior to the event.

The initial Twitter reports were matched up with this prediction by astronomer Jonathan McDowell, who we’ve had on our show before, among others, to confirm the identity of the particular piece of space debris. Space junk typically burns up during reentry, though the pressurized helium bottles called Composite Overwrap Pressure Vessels used on Falcon 9 second stages have been known to survive reentry and ground impact mostly intact.

In other SpaceX news, company CEO Elon Musk presented an update to the press on the Starship the evening of February 10. In the presentation, which we watched so you don’t have to, Musk restated the justification for the program and some key statistics and showed the progress of Raptor 2, an upgraded version of the Raptor engine. Like a typical Musk presentation, it was heavy on raunchy jokes and light on details; this was not a NASA update. He did mention that SpaceX would move Starship operations to the Cape if the FAA does not give them their launch license for Boca Chica soon.

And now, Beth and I are going to take a break from space and rocket news to review astronaut Chris Hadfield’s fiction novel, The Apollo Murders.

Review

I am going to admit something now. I don’t actually like to write book reviews. I consent to give a star rating on Goodreads, but writing actual reviews tends to leave me staring at my screen. Media consumption is deeply personal, and what one person loves another person may loathe, and far be it from me to tell you what that will be for you.

That being said, Erik and I are here to talk about the first fiction novel from astronaut Chris Hadfield, of “Space Oddity” fame. The book is called The Apollo Murders, and it’s set at the end of the Apollo era as NASA prepares for Apollo 18. The story mostly follows flight controller Kazimieras “Kaz” Zemeckis, a former test pilot who lost an eye in a freak bird collision which also dashed his hopes of becoming an astronaut.

NASA is in the middle of planning Apollo 18 when various intelligence and defense agencies step in to basically hijack the mission objectives. It seems the Soviets are doing something odd on the Moon, and NASA’s three-man team now has to go find out what that is. Erik will tell you more about the premise in a moment.

Here’s my contribution to this review: I haven’t finished the book. I read a book every two to three days, and I cannot seem to get into this one. I’m about 20% of the way in, and it’s a slog. It’s very insider baseball, which if that’s your thing, great. It is not, however, my thing and is one of the reasons I also found most Tom Clancy novels tedious. Hadfield knows a lot about both the history of NASA and the inner workings of the space programs, and even about Soviet locations and processes. And I do mean he knows A LOT. As he should.

But it’s boring. It’s overly technical to me, and while I can definitely feel Kaz’s excitement about being involved with the space program finally, it gets lost in all the technical writing. The only bit intriguing to me right now is the potential relationship developing between Kaz and a geologist assigned to the mission. She’s not an astronaut, but she wants to be, and at least Kaz is on her side for that. I want to skip through the book and see that relationship blossom. As it is, I’m not sure I’ll finish this book.

However, Erik did finish it, and he has thoughts. Erik?

Thanks, Beth. As she said, I managed to slog through the book. I know you’re supposed to let fiction do things you wouldn’t let reality do, but I just couldn’t suspend my disbelief at the premise of the mission of Apollo 18 as described in the book.

It was technically plausible, as I expected from someone with the knowledge of Chris Hadfield. It just seemed grossly unnecessary; there was no need for one mission to do all the things that it did in the book. Keeping all that a secret would be hard, and indeed in the book, the Soviets figure out the Americans’ deception rather quickly. More than one mission would be easy and having a secret second military spacecraft would have been more believable than doing everything on an Apollo lunar mission, to me. Several concepts and even programs with flight hardware contemporary to the era were available for Hadfield to choose from.

The rest of the events in the lunar mission are also suspense breaking, but what really made me almost put the book down was the gunfight in and around the capsule after landing. That was reckless but justified in the story by the valuable cargo they brought back.

Overall, I liked this book. The science and technical details were solid. Just not the action sequences.

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.