For this week’s Rocket Roundup, we have all the Chinese launches! SpaceX launches a ton of satellites on one rocket, Virgin Orbit launches a few satellites from a plane, and Virgin Galactic sends a few employees to space. Plus, this week in rocket history, we look back at the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

Podcast

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

First up, on June 30 at 14:00 UTC Virgin Orbit Launcher One successfully launched the Tubular Bells Part One mission. Cosmic Girl, a 747-400, took off from the Mojave Air and Space Port in California at 13:00 UTC carrying the rocket and headed southeast over the ocean. One hour after liftoff the plane dropped the rocket and sent it on its way to orbit. The ascent was nominal and after a brief coast phase, the second stage restarted to put the satellites in the correct orbit. There were six satellites on board, most of which were military payloads.

Next up, on June 30 at 19:31 UTC, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 Booster 1060 launched the Smallsat Transporter 2 mission from SLC-40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida.

Instead of taking the usual trajectory to the east that is used to achieve an equatorial orbit after liftoff, this Falcon 9 headed south-southeast to a polar orbit in a dogleg maneuver that skirted the Florida coast. And instead of landing on a barge, the first stage flipped around and reignited its engines opposite the direction of travel to head back to the launch site. Booster 1060 successfully landed at Landing Zone 1 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, thus completing its eighth flight.

Once in orbit, the Falcon 9 second stage began the orderly process of deploying the satellites in such a way that they wouldn’t hit each other later. This was a carefully coordinated dance of separation after separation that lasted 30 minutes.

Like other rideshare launches, SpaceX included some of its own Starlink satellites on the mission. This time there were only three Starlinks among the 88 total payloads on the rocket.

We have a lot of launches to cover this week so unfortunately, we don’t have time to talk about all 88 payloads. But there were a couple that caught our attention: Ghalib and QMR-KWT.

Ghalib by Marshall Intech is a 2U CubeSat designed to monitor the migration of falcons in the United Arab Emirates for conservation purposes. The satellite has a radio receiver and a small camera to accomplish this mission. If this demonstration is successful, Marshall Intech plans a full constellation of six CubeSats to track migratory birds worldwide.

The QMR-KWT CubeSat is the first satellite from the State of Kuwait. It was built for students for the “Code in Space” initiative. Students can submit code to be uploaded and run on the satellite. The satellite was built by Kuwaiti company Orbital Space who posted the technical details needed to send and receive data from the satellite online.

You can read more about these and other payloads on our website, DailySpace.org.

Next up, on July 1 at 12:48 UTC, Arianespace and its affiliate, Starsem, launched a Soyuz 2.1b/Fregat from the Vostochny Cosmodrome in eastern Russia.

Onboard the Soyuz were 36 satellites that made up the OneWeb 8 mission. The rocket’s Fregat upper stage conducted several engine burns over the course of two and a half hours and then inserted the 36 satellites into the target orbit in nine sets of four. This marks 254satellites launched of a planned constellation of 648 OneWeb satellites.

China launched four rockets within a week’s time. Here’s a quick rundown of them.

On July 3 at 02:51 UTC, a Chinese Long March 2D successfully launched the Jilin-01 Wideband satellite, three Jilin-03A Gaofen satellites, and a 5th satellite called Xīngshídài-10. All of the satellites in this launch have very similar missions, which can be summed up as remote sensing, land use, resource monitoring, and disaster management.

A couple of days later, on July 5 at 23:28 UTC, a Long March 4C launched the Fengyun 3E satellite from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. Fengyun 3E was developed “for meteorological forecasting, climate prediction, environmental monitoring, and disaster prevention and mitigation.” It was launched into a special type of sun-synchronous orbit, with the orbital node passages at dawn and dusk instead of the typical morning or afternoon passage for such remote sensing satellites. This type of orbit is typical of radar imaging satellites, not optical satellites like Fengyun 3E. With a dawn-passing satellite and the typical morning and afternoon satellites, the Fengyun 3 constellation can provide complete global coverage of precipitation.

On July 6 at 15:55 UTC, a Long March 3C launched the Tianlian-5 spacecraft into a geostationary transfer orbit. Tianlian is the Chinese equivalent of NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System, or TDRSS. Once Tianlian-5 reaches its slot in geostationary orbit, Tianlian-3, which launched in 2012, will be retired. The constellation is used to support communications between the Chinese Space Station, other satellites, and the ground when beyond the range of ground stations located in China.

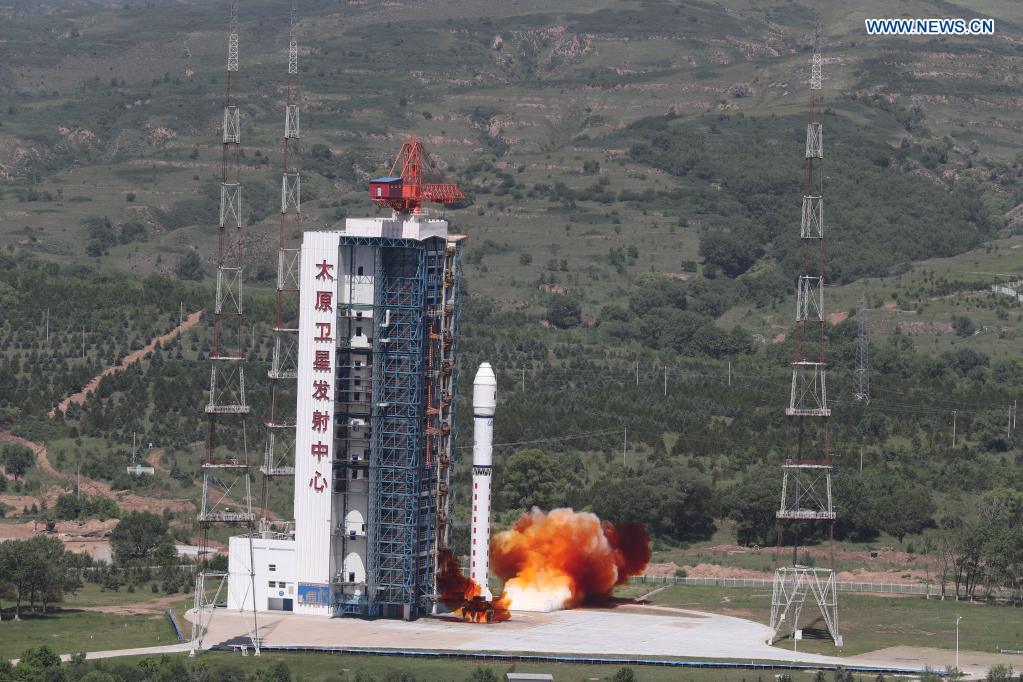

A couple of days later on July 9th at 12:59 UTC, a Long March 6 launched from the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center and added five satellites to the Zongzi 02 commercial remote sensing constellation, bringing the number of satellites in the constellation up to ten.

Finally, on July 11 at 15:25 UTC, Virgin Galactic’s VSS Unity launched on a suborbital trajectory from New Mexico’s Spaceport America. Onboard were six people: two pilots and four “mission specialists”, including company founder Sir Richard Branson. After a forty-minute flight to the drop zone, Unity was released from the mothership VMS Eve.

Unity completed one minute of powered flight and then coasted to an apogee of 85 kilometers. Along the way, it flipped over so that the windows were facing the ground, to give a better view of the Earth for the passengers. The passengers were then allowed to unbuckle and float around the cabin for a brief period. Fifteen minutes after it was released by the mothership, Unity successfully landed on the runway at Spaceport America. In a short ceremony after the flight, the passengers who hadn’t previously been in space received Virgin Galactic astronaut wings.

This Week in Rocket History

This week in rocket history is another mission of cooperation: the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

In 1968, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Rescue Agreement, which was the follow-up to the Outer Space Treaty signed in the previous year; a document that detailed the rights and responsibilities of nations who put things into space.

Yes, there are treaties that deal with outer space.

One of the main clauses of the Rescue Agreement is exactly what it sounds like: an agreement to return space travelers who land on Earth in a different country to the country they launched from. Also stipulated in the agreement is a requirement that any nation who could assist with a rescue of a crewed spacecraft was obligated to do so.

The Rescue Agreement started additional cooperation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and in 1972, a rescue demonstration was formalized as part of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT), which was an agreement to limit the number of nuclear missiles on both sides. The early plan was to dock an Apollo to one of the Salyut stations, but that plan was abandoned early on because it was too expensive to add a second docking port to the current station at the time. Instead, an Apollo would meet with just a Soyuz capsule in orbit.

One of the key problems of docking the Apollo and Soyuz capsules is the atmospheres of the two capsules. You see, the Americans played rock and roll while the Soviets played classical music. [crickets]

Actually, the problem was the Soyuz capsule was pressurized with a mix of oxygen and nitrogen at 14 psi while the Apollo used pure oxygen at 5 psi. Directly mixing the atmospheres would have caused problems. Suddenly changing external pressure around a human body is a bad idea if you want to keep those humans alive. So Soviet and American engineers designed a Docking Module as an airlock for a proper equalization of atmospheres and for the Apollo to dock to the Soyuz.

The other major problem they had to overcome was incompatible docking systems.

After iterating through many designs that included ones with several cones and others with four petals, they settled on one with three petals that faced outwards spaced 120 degrees apart called APAS-75 or Androgynous Peripheral Attachment System-1975. It could act as both an active and a passive docking port with the same hardware, depending on the configuration of six pistons which dampened docking forces.

The active spacecraft approached with the petals extended by the six pistons, while the other spacecraft retracted a ring in the system. Once the petals on the two spacecraft meshed together, the active spacecraft retracted its ring, and the two spacecraft secured the connection with some bolts. The system was tolerant of slight misalignment, with hydraulic pistons that could extend or retract to make sure the alignment was within tolerances even if it wasn’t perfect.

Another problem was fitting this docking port inside the fairing of the Soyuz rocket. Changing the fairing to accommodate a wider docking port would have changed the aerodynamics of the rocket and required expensive requalification of its flight profile. The Soviet design principle is essentially one of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”, so the port ended up smaller than the American-preferred, 90-centimeter tunnel. The port was limited to a maximum external size of 130 centimeters, with a maximum inner diameter of only 80 centimeters through which the astronauts had to pass. That’s about 40 percent bigger than a typical manhole cover. Despite the very tight fit, they were able to use it in a shirt-sleeve environment, but not a bulky spacesuit.

The crews of the Apollo and Soyuz trained for the mission in both Houston and Star City near Moscow. The Apollo crew was announced in 1973 as Tom Stafford, Eugene “Deke” Slayton, and Vance Brand. The Soyuz crew was Valeri Kubasov and Alexei Leonov. The NASA personnel and journalists became the first Americans to go to the secret cosmonaut training center, which didn’t appear on any official maps at the time.

In 1975, everything was ready. The Soyuz launched first at 12:20 UTC on July 15 from Baikonur. Seven and a half hours later at 19:50 UTC, the Apollo launched from Kennedy Space Center. The docking module was brought up with the Apollo on its Saturn 1B rocket in the space underneath the service module where the Lunar Module would be for a lunar mission.

Two days after the launch of Apollo, the two spacecraft docked at 16:10 UTC on July 17. After a slight delay due to a concern with the atmosphere in the docking module, specifically the “strong scent of burned glue”, Astronaut Brand opened the hatch to the Soyuz at 19:17 UTC.

When the five astronauts were settled, U.S. President Gerald Ford spoke to them from the White House, asking many questions about their experiences and congratulating them on their achievements. After the call, the crew exchanged gifts and a meal.

The next day the combined crews began with giving televised tours of their respective spacecraft with the Americans speaking Russian and the Russians speaking English. Another part of the TV broadcast involved zero-g science demonstrations for school children in both countries.

On July 20, 1975, the fifth day of the mission, the two spacecraft undocked at 12:12 UTC, and the Apollo backed away a few tens of meters. The spacecraft remained aligned along their axes, and the Apollo served as an improvised coronagraph for the Soyuz crew to take pictures of the Sun’s corona. At the same time, ground-based solar telescopes conducted observations allowing them to be compared later with and without atmospheric disturbance.

They docked again at 12:55 UTC with the Apollo acting as the active vessel, as it had the first docking.

Apollo deorbited at 20:37 UTC on July 24, but they almost didn’t make it to the surface alive; however, I’m happy to report that the three crew members survived the re-entry.

Overall, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Program was a successful mission for both countries that would lead to future cooperation between the two superpowers. It was also a technological dead end, with the APAS-75 port never being used again. Science – in the name of peace.

Statistics

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 7: 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz, 1 on the Shenzhou, and 1 on Tianhe

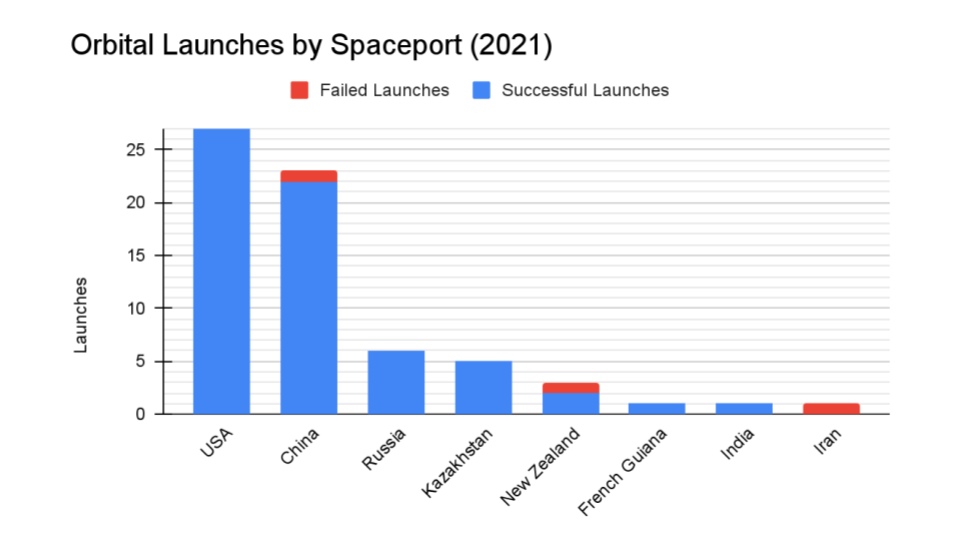

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 67, including 3 failures

Total satellites from launches: 1301

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 27

China: 23

Kazakhstan: 6

Russia: 5

New Zealand: 3

French Guinea: 1

India: 1

Iran: 1

Random Space Fact

Your random space fact is that the flight of Unity 22 broke the record for most people in space at one time for about four minutes with the crews on the ISS, Tianhe, and VSS Unity totaling sixteen persons.

Learn More

Tubular Bells Takes Off

- Virgin Orbit press release

- Launch video

SpaceX Launches Transporter 2 Rideshare

- SpaceX mission page (archive)

- ISISpace press release

- UAE press release

- Ghalib info page (ISISpace)

- QMR-KWT info page (Orbital Space)

- Launch video

More OneWeb Sats Added to Constellation

China Goes on a Rocket Launching Spree

- CASC Jilin-1 press release (Chinese)

- CASC Fengyun-3E press release (Chinese)

- CASC Tianlian-1 05 press release (Chinese)

- Launch video

- CASC Zhongzi press release (Chinese)

- Zhongzi info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

Space Tourism Starts with VSS Unity Flight

- Virgin Galactic press release

This Week in Rocket History: Apollo-Soyuz

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.