Today remember the heroes NASA has lost in its three winter space craft disasters. It is hard, but it is important. We also bring you a note about the Spitzer Space Telescope and it’s final days and observations

If you are Gen X like me, you may hear that date, and remember exactly where you were in in 1986 when the Challenger lifted off but failed to reach orbit. 34 years ago today, during middle school lunch block on the East coast, the Space Shuttle Challenger lifted off from Cape Canaveral, with a crew of 6 astronauts and one schoolteacher from New Hampshire.

For each of the older generations there has been this kind of a winter disaster. For the boomers, there was the Jan 27, 1967 loss of Apollo 1. The 3-man crew lost their lives during a preflight test when a spark ignited their cabin’s oxygen atmosphere.

For Millenials there were was the February 1, 2003 loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia, which disintegrated during re-entry.

One of the things we talk about a lot here on CosmoQuest is the simple fact that space is hard. Getting to space is one of the most challenging things a machine with or without humans can accomplish, and the only task that is more challenging is getting to the bottom of the ocean. It is amazing that so few astronauts die.

This month, we saw the inflight abort test of the SpaceX Crew Dragon Capsule. That successful test sets us up to start sending astronauts to space in a brand new spacecraft. As we do that, it is important for us to both remember past tragedies, and not let them hold us back.

The crew of Space Shuttle mission STS-51-L pose for their official portrait on November 15, 1985. In the back row from left to right: Ellison S. Onizuka, Sharon Christa McAuliffe, Greg Jarvis, and Judy Resnik. In the front row from left to right: Michael J. Smith, Dick Scobee, and Ron McNair.

I was in the 6th grade when the Challenger was lost 73 seconds after launch. It was the cold that killed the 7 men and women on their way to space. Plastic loses its ability to flex and bend in the cold, and that day in Florida it was just below freezing. Each of the sections of the solid rocket boosters are sealed with plastic O-rings that are designed to prevent exhaust from leaking or combusting through the seams between the segments. When these seals fail, the gas in the rockets has more than one way to go – It can either go out the bottom of the rocket, or out through the faulty seal. These O-rings are in many ways no different than the tape you use on the gas connectors for a gas stove or the plastic rings in faucet handles. On that too-cold day, the O-ring had contracted, and the gas escaped.

The solid rocket booster exploded. The shuttle shattered. The crew cabin fell to the sea, as seven men and women struggled to use their training to figure out how to survive. An oxygen tank was turned on. We know they lived through the blast. They, like every other astronaut we’ve lost, had the time to realize, “OMG, I am about to die.”

But their experience hasn’t deterred people from wanting to become astronauts. Their deaths, in front of an entire generation of school children, didn’t cause the children to turn away from space and stop dreaming. NASA had, without meaning to, created a martyr for everyone – in each of those astronauts each of us could, if we wanted to, find someone whose dream we could define in our own new way.

We may be just months from the launch of humans on board a SpaceX Crew Dragon. It is unclear at this time how long it will be until humans launch on Boeing’s Starliner capsule, but it could be just half a year.

As we prepare to return to space on this still-to-be-proven new spacecraft, we need to remember that space is hard. There will be loss of life again. And we need to remember that the astronauts accept that risk when they sign up. We need to do right by them, and remember that every time life has been lost it has been due to engineering failures. From Apollo we learned that spacecraft need to be easy to exit, and the door was changed from opening in, to opening out. We also learned that a pure oxygen atmosphere is too risky. From Challenger we learned to listen to engineers and not push our systems all the way up against their temperature limits. From Colombia we learned again – because sometimes once isn’t enough – that cold and plastics don’t mix, as it was determined that falling cold foam bouncing against the Shuttle’s wing was what created the damage that led to the loss of life. We learned. And now we need to not forget.

As we move forward, let’s celebrate the lives of those who died in the pursuit of space, and let’s be inspired to one again dare mighty things… but with care and in collaboration, and while remembering to listen to our engineers.

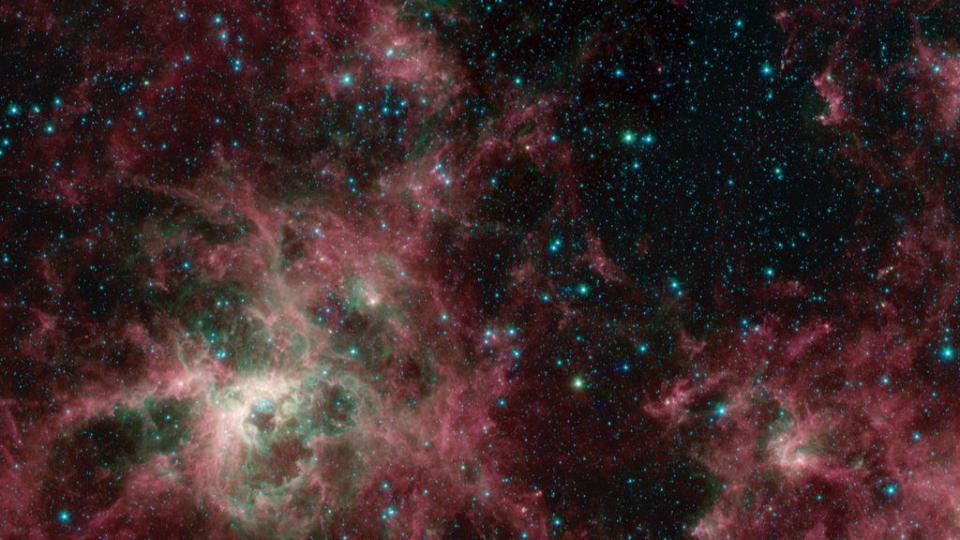

Ok, before I tie up this episode I do want to give you one pretty picture from science. Later this week the Spitzer Space Telescope will be retired from use as NASA makes space in its budget and organizational structure for the upcoming JWST. As part of the missions winding down, we’re getting new data of old favorites, and today’s release brings us the Southern Hemisphere’s Tarantula Nebula. The region of illuminated dust was one of Spitzer’s first targets, and has been revisited year after year, with data being taken in 2003, 2006, and now in 2019. This data has allowed us to see stars forming, to identify the role of silicates in the dust, and to monitor the expanding shockwaves from supernova 1987a.

While the image has been released, the totality of the science is still to come, and we look forward to bringing you those results when we have them.

<———————>

And that rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you. Want to become a supporter of the show? Check us out at Patreon.com/cosmoquestx

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode on Twitch.tv, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.