Today we start off with a quick take on everyone’s favorite fading star, Betelgeuse. This red giant is fading away right before the eyes of anyone with clear skies, and we don’t know why, and many hope it might be gearing up to explode (but it probably isn’t). Join us as we discuss what we do and don’t know about this system. We also take a quick look at new ways to study 3-body systems with statistics, and new research that use stats to show that our solar system is likely ripe with alien small objects, like comets and asteroids.

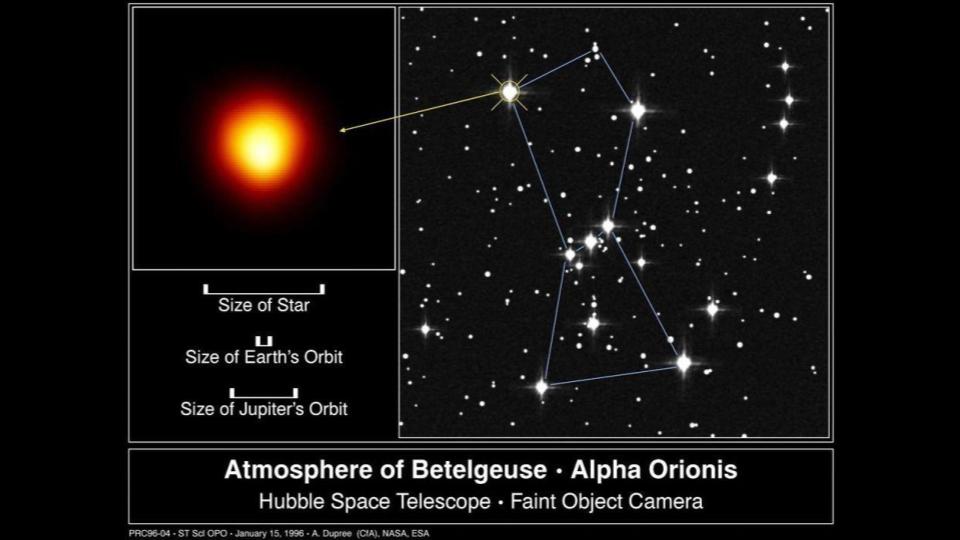

Today’s news is so far much less exciting than I might have wanted. The red giant star, Betelgeuse, the shoulder of Orion, is decreasing in brightness in ways that haven’t been noted in the past, and hasn’t been seen during the past 50 years of modern measuring. Where Betelgeuse had been the brightest star in its constellation, it now appears oddly faint such that this familiar constellation looks super weird. Why is Betelgeuse suddenly dropping in brightness? No idea.

And it’s that lack of knowing why that is so exciting, because in the absence of knowledge is space to wildly speculate, and one of the things we are speculating could happen is that Betelgeuse could be gearing up to go supernova in the immediate future.

Here is what we know. Betelgeuse is a massive star that should live no more than 10 million years and is now at least 9 million years old. When it dies, it will go supernova. At this stage in its evolution, this 10+ solar mass star is forming a cloud of material around itself as it exhales its atmosphere through a massive stellar wind. It is semi-regularly pulsating, and in recent decades has had a period of roughly 400 days. While its brightness variations haven’t been what anyone would call consistent, it is now noticeably fainter than has been seen.

Here is what we don’t know: We don’t know exactly what stars of this size do directly before they go supernova. If they do something interesting before they explode, we don’t know how long they do that interesting thing for before they explode. We don’t know how often massive stars have false nova events, where they flare up in brightness but don’t actually explode. Basically, since large stars are rare, and duration of time before a supernova is short, we simply haven’t yet been able to identify stars that are about to explode prior to them exploding such that we could document the star in detail in the decades and centuries leading up to a supernova.

So… we are all hoping that Betelgeuse’s strange behavior means it’s about to go supernova at any second, while we simultaneously recognize that it is probably not going to explode until some distant date outside of our imaginable future.

But we’re still hoping it will explode now. If that happens, which it probably won’t, it would be 10x brighter than Venus and easily seen in a clear daytime sky. Overtime it would fade, but it wouldn’t disappear. Betelgeuse is roughly 650 ly away this is 10x closer than the Crab Nebula, which was produced by a bright supernova in 1054. That nebula can be seen with binoculars and any supernova remnant from Betelgeuse will be visible by eye, and in time will make Orion appear to have a chaotic wound in the space long associated with his shoulder.

The next month is going to be a particularly interesting time. Villanova astronomer Ed Guinan has been studying Betelgeuse for decades and predicts that it should begin to increase in brightness in the next month. This change should be apparent to the unaided eye, and if you go out and compare it in brightness to nearby stars on a consistent basis, you should be able to see its changes for yourself. Since this is an equatorial constellation, people in both hemispheres can follow along and watch to see if this star acts weirder and weirder or simply returns to normal.

I, for one, am hoping for something weird, but recognize that the universe doesn’t care what I hope or want.

Beyond Betelgeuse confusing everyone with is dropping brightness, it has been a fairly quiet time for space science. This is in part due to the holidays, the end of the semester grading, and the fact that next week will be a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu, Hawaii. I will be there, and will be doing what I can to bring everything to you. Because of the extreme time difference, I will not be coming to you at our normal time, and instead other folks will be holding down the fort. If the internet allows, we will have other live streams as we are able.

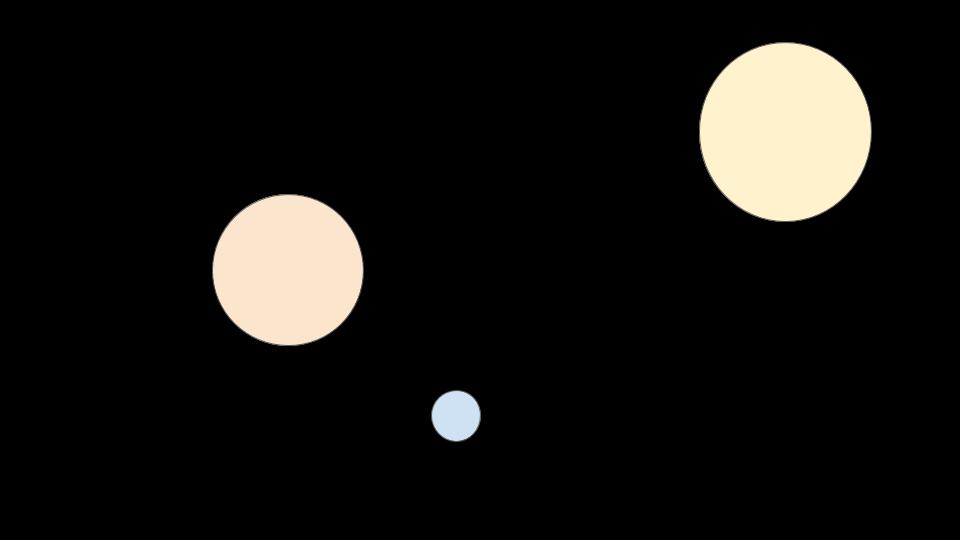

Quiet news doesn’t mean no news however. There were two stories that caught our eyes in the past week. The first is a release from Hebrew University that highlights a paper in Nature that takes a new look at the three-body problem. It is possible to have a system of 3 orbiting objects that are stable if the objects have very different sizes. You can easily end up with situations where a smaller object orbits two large objects that are close together, or where a small object orbits 1 of 2 large objects with a large separation, and of course you can have two small objects orbit a large object in all manner of ways. What you can’t have is 3 objects of similar mass that orbit one another in a way that stays stable. Over time, it appears that all three body systems, including triple black hole systems in the centers of merging galaxies, will eject one of the three objects. How, when, and even which is basically impossible to predict, but in this new work by Nicholas Stone and Nathan Leigh, they find that in some cases it is possible to use statistical analysis of model systems to predict what should happen. These scenarios, which are called resonant encounters, are the ~50% of three body encounters that undergo chaotic evolution. By modeling many possible encounters, they can see patterns in the outcomes that can be used to predict the most likely future scenarios. According to the paper, there are a number of astrophysical uses of this information, “For example, non-hierarchical triples produced dynamically in globular clusters are a primary formation channel for black hole mergers, but the rates and properties of the resulting gravitational waves depend on the distribution of post-disintegration eccentricities.”

- Capturing alien comets (Planet S)

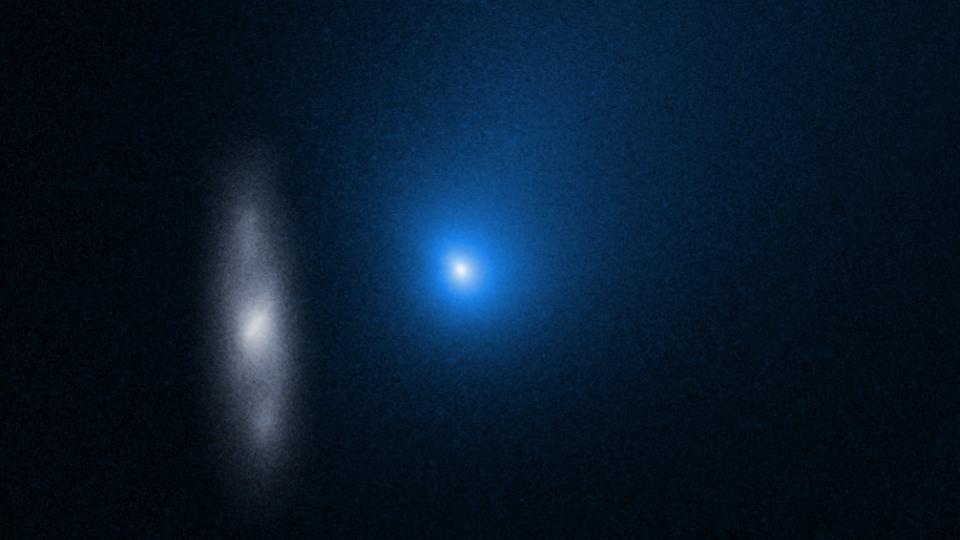

Statistics is one of the least exciting ways that we advance science, but it produces some of the most eye opening results. In a different statistics based study, T Hands and W Dehnen write in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society that at any time, approximately 100 to 10,000 comets in our solar system originated in another solar system. Many of these objects will end up in orbits that make it impossible to distinguish them from long-period comets that originated in our solar system. To get at this cool discovery, they considered how small bodies with velocities typical of our local stellar velocity distribution will interact with our sun and Jupiter, and either get captured or fly away. They ran over 400 million simulations and found that it may not be possible to distinguish the orbits of these interstellar interlopers from objects that formed in our own solar system.

Put another way, there are quite likely aliens among us … or at least among our comets … and we may never know who they are.

<———————>

And that rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you. Want to become a supporter of the show? Check us out at Patreon.com/cosmoquestx

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode on Twitch.tv, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you can help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let your friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do!

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.