In this episode we do a deep dive into the news about a possible 70ish solar mass black hole in our galaxy and discuss why it could (but might not be correct), and what that means. As a palate cleanser, we take a taste of Mars dust storms, and provide a reminder about the interstellar comet, Borisov.

This is the Daily Space for today, Monday, December 2, 2019. I am your host, Dr Pamela Gay, and I am here to put science in your brain.

———————

- Chinese Academy of Sciences leads discovery of unpredicted stellar black hole (Press Release)

- This Newfound Monster Black Hole Is Too Big for Theories to Handle (Space.com)

- Scientists discover unpredicted stellar black hole (Phys.org)

Last week was a slow news week as the holidays over ran everyone’s work week. There was one story that still managed to not get drowned in the egg nog: the story of the potential discovery of a 68 Solar mass black hole right here in our Milky Way. In a new paper in the journal Nature, a team lead by Liu Jigeng of the National Astronomy Observatory of China announced they had found a new black hole by looking for the anomalous motions of stars that indicated the presence of a dark companion. In this case, they were able to see a star they assume to be about 8x more massive than the Sun orbiting an unseen object every 79 days. While this size black hole is weird by itself, what makes this result really weird is their belief that this black hole would have formed through the death of a single star.

You may have noticed that I’ve used words like “potential,” “belief,” and “assume”. This is because this is one of those papers in Nature that is possibly true, but is very easily very wrong. Both the journals Nature and Science publish things that are potentially ground-breaking, Nobel prize winning results… or just preliminary and not yet fully-baked. I’m not sure what percentage of papers are later proven wrong, but it’s a high enough potential that folks joke about it.

So, what do we need to worry about with this discovery? The presence of a dark object of some kind isn’t in doubt. They’ve seen a star orbiting something regularly using multiple telescopes. This is essentially a binary system where we can measure the period well, but struggle to get at other needed information like the size and inclination of the orbit. They make estimates on the orbital size based on an assumed distance, which is based on an assumed star type and luminosity. That’s a whole lot of assumptions, and they correctly point out that there “interpretation of an extraordinary 70M☉ dark mass … will be undermined if the companion mass is substantially lower than the 8M☉”.

The 8M☉ size came from looking at a combination of factors including its temperature and surface gravity, which is an indicator of its size. In order to match this size of a star with the observed brightness of the star, the star had to be quite far away… 13,800ly away … which made the black hole really big. The thing is, according to the Gaia mission, this particular star is only 7000 ly away. Using this new distance and everything it entails changes the black hole mass all the way down to 10 solar masses, which is a totally normal mass for a stellar mass black hole.

But what if their distance is correct? Well, now we have to think harder about this being a black hole that was generated by a single star. If it was from a single star. It would need to be a star with an initial mass of something like 200M☉… and we haven’t seen that yet. We haven’t seen even 100M☉ stars! But maybe this star comes from a time when stars could form much larger, and it just happens that it captured a much younger star and now lives in a generally youthful part of our galaxy. This is possible. It’s also possible that this black hole had a more complicated origin and formed through the merger of smaller but still massive objects, such as two black holes or a black hole and a massive young star. We know this happens – LIGO has measured gravitational waves from this kind of object, but it’s unknown if this particular system could have formed and settled into its observed circular orbit.

And here is the thing – all these “it could be” possibilities are raised in the Nature paper that led to so many news articles. The thing is, all these “it could be” possibilities don’t make as click-bait of a headline or as exciting of a story, so the lede gets buried.

The thing is, all those stories failed to highlight one of the most exciting parts of this study. This team is finding black holes that are unlike anything we’ve found before – they are boring black holes orbiting with non-disrupted stars. They aren’t giving off X rays or Gamma rays. They are just being large dark masses… and they are getting found because of how they fling around their neighbors. This is new, and this is going to give us an entirely new census of what large hidden objects are out their waiting to not be seen.

- Global Storms on Mars Launch Dust Towers Into the Sky (JPL)

- When Martian Storms Really Get Going, they Create Towers of Dust 80 Kilometers High (Universe Today)

- Mars’ Intense Storms Can Create Towers of Dust 80 Km High And The Size of Nebraska (Science Alert)

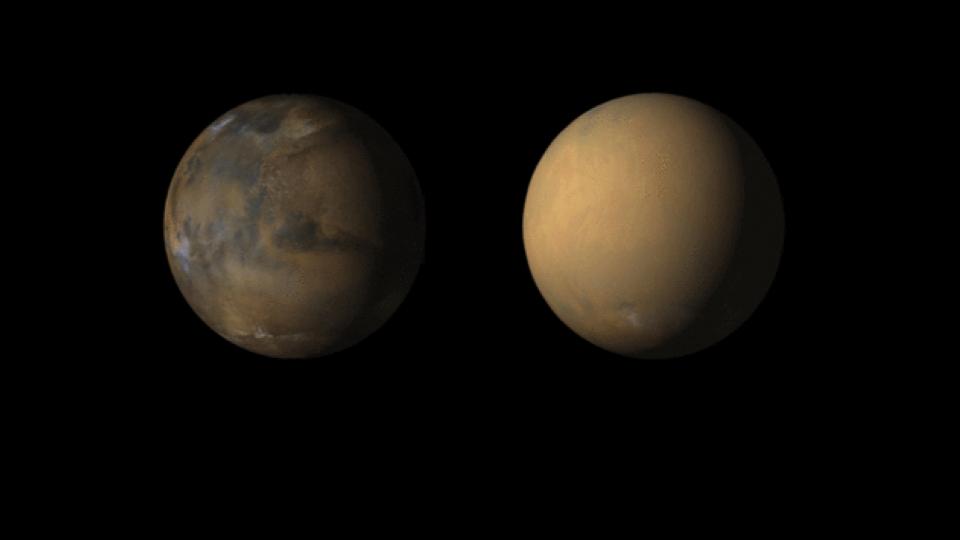

Ok, that story was a bit challenging. Let’s switch to something entirely different as a palate cleanser. In two new papers led by Nicholas Heavens, planetary scientists look at how dust is lofted into the air during Martian dust storms. In 2018, a massive storm enveloped Mars, thickening the atmosphere with light blocking materials that caused the Opportunity rover to lose power and eventually lose its digital life. While we were all hurt to lose Opportunity, the wealth of other missions at the Red Planet allowed us to use that storm to study Mars dust storms like never before. Data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter found that dust towers rose to heights of 50 miles or 80km. These systems were able to pump dust into the atmosphere for more than 3 weeks.

In addition to cloaking the world with dust, these storms have a devastating effect on the water on mars. Water trapped in Mars dust gets released to form wispy clouds, and is lofted with the dust into the upper atmosphere, where sunlight can break down the water molecules and allow the atoms to escape into space. This channeling of moisture may have played a role in stripping Mars of its early water, accelerating the desertification of this once wet world.

This kind of planet wide storm is something we luckily don’t have on Earth, and understanding them is going to be imperative to figuring out how we can someday survive on Mars.

- New image offers close-up view of interstellar comet (Yale News)

- Interstellar Comet Borisov is About to Make its Closest Approach to Earth (Universe Today)

- Interstellar Comet Borisov Shines in New Photo (Space.com)

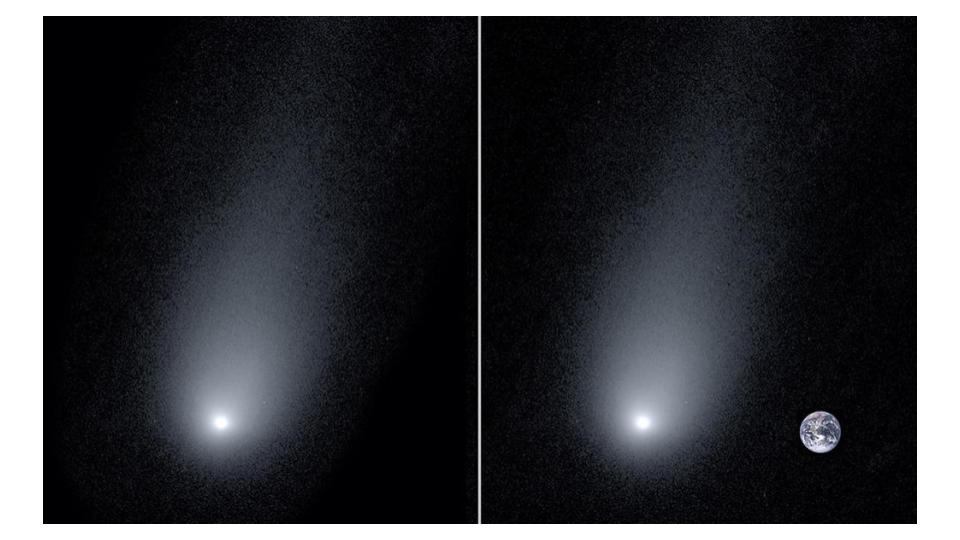

And finally, I’d like to remind you that comet 2I/Borisov is continuing its journey through our Solar System. This month it will make its closest approach to the sun before heading back out toward the great unknown. This is an active comet with a quickly growing tail that now stretches 100,000 miles. It was most recently imaged by the Keck Telescope in Hawaii and you can view that image on our website, the DailySpace.org.

—————-

And that rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you. Want to become a supporter of the show? Check us out at Patreon.com/cosmoquestx

I will now take your questions, and ask you to please at CosmoQuestX to help me find them in the chat. While you type them in, let me remind you that the Daily Space is a production of the Planetary Science Institute, and is hosted by myself and Annie Wilson.

We’ve launched a podcast edition of this show. If you want a 10 minute, chaos-free listen, click over to dailyspace.org and check it out. Find it wherever you get your podcasts!

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode on Twitch.tv, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you can help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let you friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.