Annie goes over last weeks launches which include the second set of Starlink satellites, and two surprise Chinese launches that occurred just hours apart. Plus an update on the Boeing parachute failure and some more details about the new Chinese gridfins.

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space for today November 13, 2019. I am your host Annie Wilson. Most Mondays through Fridays, our team will be here bringing you a quick rundown of all that is new in space and astronomy.

- Starlink (satellite constellation) (Wikipedia)

- Falcon 9 booster B1048 (Wikipedia)

- Starlink-2 (60x) (Rocketlaunch.Live)

First up: SpaceX’s launched the second installation of the Starlink constellation to space aboard a Falcon 9. Liftoff was Monday, November 11, 2019 at 2:56 PM (UTC) carrying 60 Starlink satellites.

- Launch video on YouTube

- Start at 13:52ish for launch

- Skip to 23:22 for booster landing

- Skip to 1:16:00 for prep of payload separation (at 1:15:00 there’s an explanation of separation)

A few firsts for this launch:

- A fairing was flown for a second time.

- The fourth launch — and recovery — of a booster. According to SpaceX, each booster can be flown ten times!

Rough seas prevented a catch, but the fairing halves were successfully pulled from the ocean.

This was also the heaviest SpaceX payload to date: 34,000 lbs / 15,600 kg (15.6 metric tonnes)

The reason this set of 60 is so much heavier than the first set of 60 is because of the upgrades to this batch of satellites: all 60 have full Ku- & Ka-band antenna sets as well as having slightly different construction to ensure full “demisability.” (That just means that it’ll ALL for sure burn up in the atmosphere instead of having pieces survive and either hang out as space junk or fall to the Earth.) The 1st batch only had the Ku antennas mounted. Also, there’s talk of upgrades to the safety/maneuvering system, making them more fully autonomous in terms of collision avoidance. Which means that there would be no need to wait for ground controllers if the data are already available from the USAF.

Reflection mitigation measures will be included on the next batch of Starlink satellites, and going forward.

The satellites are pretty clumped up now, but will spread out over time.

SpaceX is now in the number two slot for the number of working satellites in orbit, passing up Iridium which previously held the spot with 106 satellites. It’ll probably take another two launches of 60 satellites each to surpass Planet (formally Planet Labs) for the top spot.

- Planet: 197 Earth observation satellites

- SpaceX: 120 internet-beaming satellites (117 after contact was lost with three in May; expected to deorbit and burn up)

- Iridium: 106 communications satellites

- Air Force: A mix of 98 classified, communications, Earth observation, position and navigation, and technology development satellites

- Spire: 85 Earth observation satellites

- NASA: 67 science, Earth science, technology development, and communications satellites (includes International Space Station)

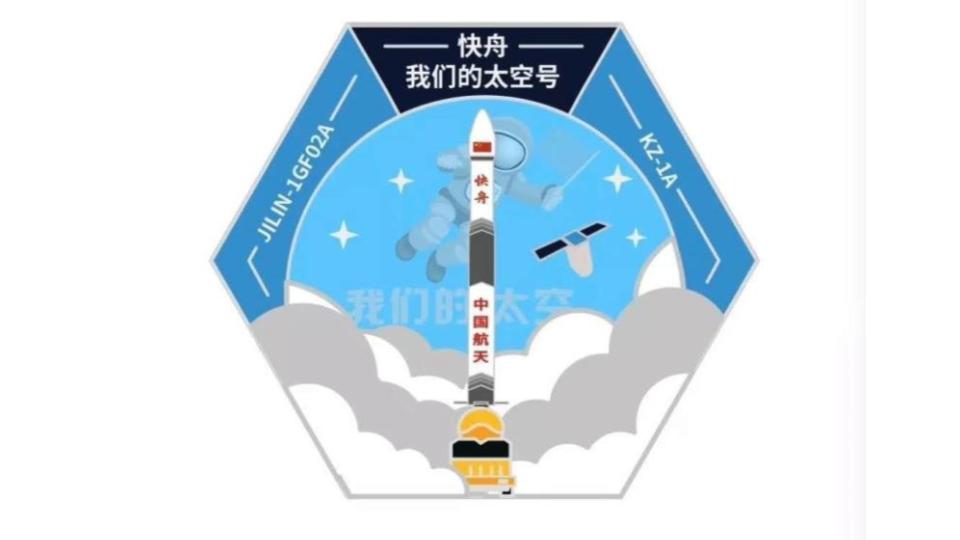

Our next launch was ExPace, which is the commercial side of China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (a state-owned group). They launched the Jilin-1 Gaofen 02A mission on a Kuài zhōu 1A rocket at 03:40 UTC.

Mission patch for this ExPace mission is in shape of a hexagon, with the rocket on the Transporter-Erector-Launcher front and center. In the background, there are 4 stars, a satellite and an astronaut holding a flag. The outline of the satellite is the Jilin-1 Gaofen 02A (which is actually the 14th satellite for this constellation). The four stars represent the number of launches for this particular model of rocket. The astronaut holding the flag is part of the logo for Our Space, a Chinese sanctioned agency that covers aerospace news. Their logo was incorporated because the first launch attempt was live-streamed in conjugation with OurSpace — extremely rare for a Chinese launch.

- Two Chinese satellite launchers lift off three hours apart (Spaceflight Now)

- Kuaizhou-1 (KZ-1) / Fei Tian 1 (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Jilin-1 High Resolution-02A, 03A (Jilin-1 Gaofen-02A, 03A) (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Launch video on YouTube

I will freely admit that this launch snuck up on me, so I don’t have a lot of info. I do know that the five Ningxia 1 satellites are part of a commercial project for a remote sensing detection mission. These satellites could possibly be used for a signals intelligence mission, where data is gathered for use by the military.

CREDIT: Stephen Clark, columnist for SpaceFlightNow.com

Last week we reported on the Boeing pad abort test that occurred on Monday November 4th. In most respects the test was a resounding success, as the craft performed exactly as planned in all aspects of its flight…with the exception of one detail: the parachutes.

- Alternate view of CST-100 Starliner Pad Abort Test on YouTube CREDIT: Stephen Clark on YouTube / SpaceFlightNow.com

Here’s some terminology you need to know before we dive into what happened. The Starliner has three sets of parachutes: drogue, pilot, and main. The drogue parachutes slow the craft before the pilot parachutes open to help the main parachutes to deploy.

During the morning test at the White Sands Missile Range all three drogue chutes were seen to deploy as planned following the 5 sec., 5.1 G burn of the capsule’s engines, which hurled it over 1,300 m / 4,400 feet into the sky. The 3 pilot parachutes then deployed as planned, intended to provide the force needed to deploy those large, heavy mains from their tightly packed storage modules atop the craft. However, only two of the main parachutes followed.

DON’T PANIC: the Starliner has actually been tested and designed to land safely with only two of the main parachutes deployed. While it wouldn’t be a particularly comfortable landing for astronauts inside the craft, they would survive the landing.

A post-flight inspection of the drogues & mains revealed the cause of the failure and there is some good news. The third main parachute didn’t deploy due to a seemingly mundane and easily solved problem: human error.

John Mulholland, Boeing’s commercial crew vice president and Starliner program manager, confirmed later that the “lack of an adequate connection” caused the one pilot chute to deploy without pulling its main out behind it.

“In this particular case, that pin wasn’t through the loop, but it wasn’t discovered in initial visual inspection because of that protective sheath.” [end quote]

Kathy Lueders, manager of NASA’s commercial crew program, said that NASA’s usual process checks — which were not in place, due to the purely testing nature of this flight — would have caught the error in an actual crewed mission.

An uncrewed version of the CST-100 Starliner is currently undergoing pre-flight integration at Kennedy Space Center in preparation for a cargo-carrying test flight to the ISS next month.

That wraps up our news for the day!

Thank you all for listening. Today’s script was written by myself and Dave Ballard. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are made possible through the generous contributions of people like you. If you would like to learn more, please check us out on patreon.com/cosmoquestx

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.