We are hitting the November doldrums, where faculty are giving and grading midterms, everyone is writing grants, and research is being held on to as we look ahead to the major conferences of December and January. This means our episodes are going to be a little different on slow news days, which is what today is, and we’re going to do deeper dives into specific problems. As we promised last week, today’s deep dive is going to be into the latest news on Pluto, New Horizons, and hopes for a future orbiter.

This is the Daily Space for today, Friday, November 1, 2019. I am your host, Dr Pamela Gay, and I am here to put science in your brain.

Most Mondays through Fridays, either I or my co-host Annie Wilson, will be here bringing you a quick rundown of all that is new in space and astronomy.

We are hitting the November doldrums, where faculty are giving and grading midterms, everyone is writing grants, and research is being held on to as we look ahead to the major conferences of December and January. This means our episodes are going to be a little different on slow news days, which is what today is, and we’re going to do deeper dives into specific problems. As we promised last week, today’s deep dive is going to be into the latest news on Pluto, New Horizons, and hopes for a future orbiter.

Last week, we got news that NASA had funded the Southwest Research Institute to study what it would take to put an orbiter around Pluto. The Southwest Research Institute is home to much of the New Horizons team, and this new study will involve many of the same people, but given the probable two-decade timescale needed to potentially plan and implement this kind of a mission, this is very much a multigenerational team.

The desire to put so many years of effort into one spacecraft is ignited by the amazing imagery that came back from the 2015 New Horizons fly-by of Pluto – And when I say amazing I don’t just refer to it’s beauty, I also refer to its science.

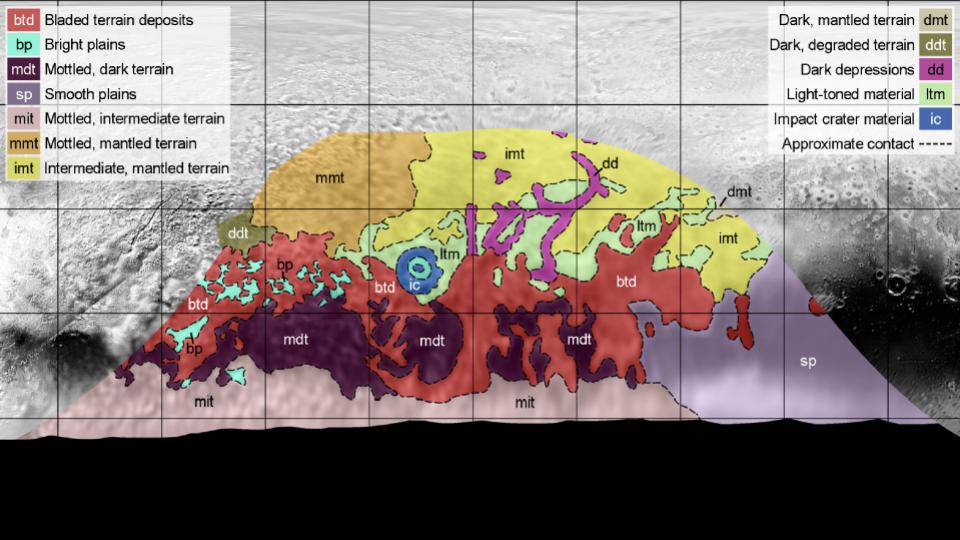

Prior to the New Horizons encounter, we imaged Pluto would be a bleak, mottled world covered in craters and not showing any signs of geologic activity. What we got instead is a world of glaciers, tectonic uplifts, and mottled and spiky terrains.

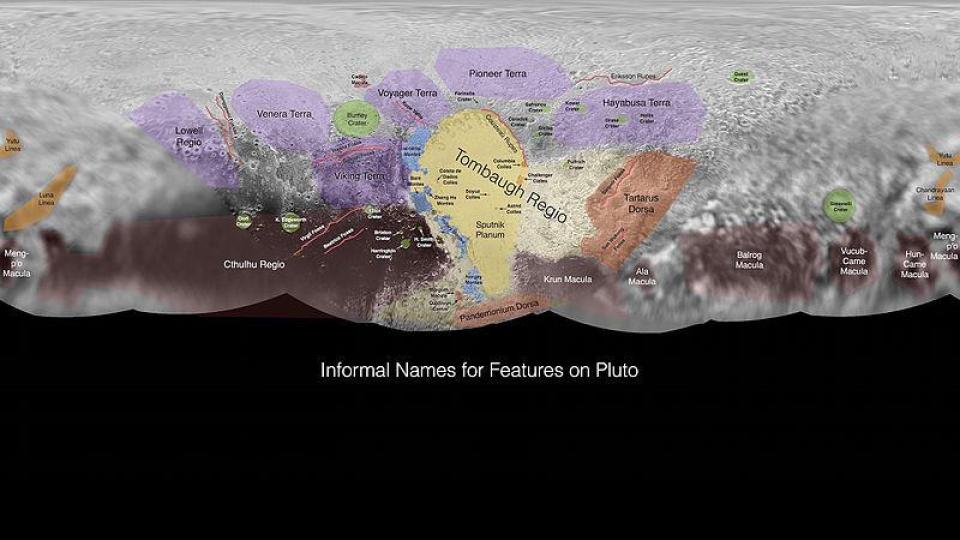

Last week, a new publication posted on ArXiv rounded out our understanding by bringing us maps of Pluto’s farside, and with the new world wrapping terrain maps, the time to discuss Pluto’s geology is now.

As we discussed last week, we don’t have equal imaging of both sides of Pluto. As New Horizons flew past, it was only able to get high resolution imaging of one side, which is now referred to as the near side. Pluto rotates with a 6.4 Earth Day period, and as New Horizons approached at 36,000 miles per hour it snapped photo after photo, catching images of the far side from far distances. The difference in distance between nearside and farside images means we were able to see the nearside with resolutions of roughly 80 meters per pixel, while the farside was seen at more like 5 to 30 km per pixel. Nevertheless, even the worst of New Horizons images are more than more than 15x better than what we’ve been able to achieve with HST, and are comparable to the best we can possibly hope to get with future 30-m telescopes here on Earth.

Let’s start by considering the nearside. The great heart of Pluto, Sputnik Planum, was the first feature to capture our attention. It is now thought that this asymmetric feature may be a massive impact basic that was formed by something massive that hit Pluto at a low angle. In general, craters are round, no matter what angle they come in from. This is because it is the shock wave from their impact energy that generates the crater, and not the impactor itself. If something comes in at a shallow enough angle, however, the impactor may break up or ricochet creating multiple impacts that appear as a single elongated crater, such as the asymmetric basin that we see as Pluto’s heart. Giant impacts like this have the ability to create features on the opposite side of the world, both through the convergence of shockwaves that travel through the world’s surface, and through the accumulation of materials that was flung out of the crater during impact and travelled around the world. This is the kind of material that we see in the bright rays on the Moon that radiate away from Copernicus crater. On Pluto’s farside, dark ridges are seen to antipodal, or opposite throughout the world from the potential center of impact. This disrupted terrain may be the result of the surface of pluto getting disrupted during the formation of Sputnik Planitia.

In the midst of this chaos are what to me are the most fascinating features – the bladed terrain. Rising up like blunt knives from the surface of Pluto, these 300 m tall features top the highest elevation terrain and appear to be methane penitentes – features that are formed as methane ice sublimates to gas and leaves behind thin leaves of material. We have similar water ice features in the high mountains of Chile, but prior to seeing these on Pluto, we hadn’t generally anticipated seeing features like this elsewhere in our solar system.

Sputnik Planitia and it’s associated antipodal features overlay a much older set of ridges and troughs that circle Pluto roughly North-South. These ancient features are considered to be the result of pluto expanding as it solidified. Called extensional tectonism, these ridges come from Pluto having a water ice Lithosphere. As it thickened, it pushed out the surface creating the ridge troughs along what was Pluto’s Equator. Exactly how this band went from being at Pluto’s equator to now marking roughly its North and South poles is still up for debate. One theory is that the event that shaped Sputnik Plantia redistributed the mass of Pluto such that it rotated to have its current orientation relative relative to Charon.

In the epochs since that reorientation occurred, Pluto’s surface has had time to evolve to match the modern orientation in coloration. Wrapping almost all the way around Pluto, interrupted only by the massive Sputnik Planitia, is a dark mottled band that includes the Cthulhu Macula, Balrog Macula and Krun Macula. This band is uniquely positioned within a region of Pluto that always has a day -night cycle. Like Earth and Mars, Pluto also has a tilt relative – only it’s tilt is much greater! It is flipped 30degrees passed normal, which means it’s north rotational pole is tilted down below the disk of the solar system. This extreme tilt means that most of the world is either experiencing the midnight sun or daylong night most of the time. There is, however, a narrow region of the world that always has day and night, and that narrow region corresponds with where the dark mottled macula on Pluto are found. It’s thought that this region is kept warm enough by the Sun that fresh, bright, material is unable to settle there. At the same time, the bright spots in low lying areas to the north and south are thought to be cold traps that collect frozen gases.

These are just what are some of the most amazing highlights of Pluto’s amazing terrain. I suspect that as new papers come out, we will be returning to this world in the future. There is still much to learn about its glacier, about the convection cells in its nitrogen plains, and about its ice block mountains. As I said at the beginning of this episode, it will be at least 20 years, or an entire generation before we can return to this outer world, so many of the mysteries of its surface are unlikely to be answered during my career. There are some things that may be answered however. While the future tens of meter class telescopes will have no better than 30km per pixel resolution of Pluto, they will have spectroscopic capabilities that New Horizons didn’t have, and they may be able to help us understand the distribution of chemicals on Pluto’s surface. It is the place to place differences in chemistry that have led to different kinds of formations we see, from the methane ice bladed terrain to the nitrogen plains to the water ice mountains and more. Only through the combined knowledge of both the chemistry and morphology can we build accurate models of what we see, and with Pluto, it looks like we’ll take things in one detail and one decade at a time.

——————–

That rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are made possible through the generous contributions of people like you. If you would like to learn more, please check us out on patreon.com/cosmoquestx During the month of November we are running a special fundraiser to support our server costs for 2020. We project costs of $1450 for all of our websites. If you would like to help us

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode here on Twitch.tv, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you can help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let you friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.