Across the centuries, people of all kinds have contributed to the field we now call science. From early developments in mathematics, to systematic observations of how objects move in the sky, and changes take place in the landscape, we’ve seen people systematically observing the world around them, looking to see what is mathematically definable, and sharing what they learn.

It is this last part – sharing what they learn – that makes someone a scientist. If you go outside tonight, and you observe a bright spot on the surface of Saturn or Jupiter, or even on the shadowed side of the Moon, but you never tell anyone beyond the lightning bugs in the yard with you, that is not science. If you document the time of your observations and where on the surface it appeared and share that information to researchers so your results can potentially be confirmed, that is science.

And that example I just gave – that’s just one kind of research that amateur astronomers contribute to all the time. This kind of science is made possible by modern digital detectors, and the first discovery was made on Anthony Wesley on June 3, 2009. Other kinds of discoveries have been taking place almost since telescopes were invented more than 400 years ago, with the most impressive collection of discoveries, in my opinion, belonging to William and Caroline Hershel.

William Herschel: Amateur astronomer turned pro

William Herschel was originally a musician. He played the piano, the oboe, and the cello. he was the composer of 24 symphonies and in his spare time managed to discover Uranus, two moons of Saturn, Mimas and Enceladus; as well as two moons of Uranus, Titania and Oberon. He studied proper motions, catalogued double stars and nebulae, and is renowned for building some of the first great observatories. In 1872, William left behind his life as a musician and accepted a position with a pay cut as the Royal astronomer.

And the way he got engaged in astronomy is a story that even today would sound familiar. In 1873, William Herschel found his passion in the stars. Between a book he was given, and a friend who talked him into observing, he got hooked. He started building telescopes. He started studying the sky and recording everything he saw. And one day in 1881 he saw a small blue disk and a few days later he saw that it had moved. At first he thought it was a comet – just another wandering traveler shooting through our solar system – but with careful observation he came to realize that he had actually discovered the 7th planet in our Solar System, and the first new planet discovered during all of recorded history. Herschel wasn’t looking to make a discovery. He was just looking. And the more he looked, the more he discovered. Herschel realized as he hopped from known star to known nebulae, that between all the known objects in the sky was a whole host of undiscovered faint fuzzy bits – what we now know as galaxies and star forming regions – all just waiting to be discovered. He followed his passion for the stars until it led him to a whole new understanding of the cosmos.

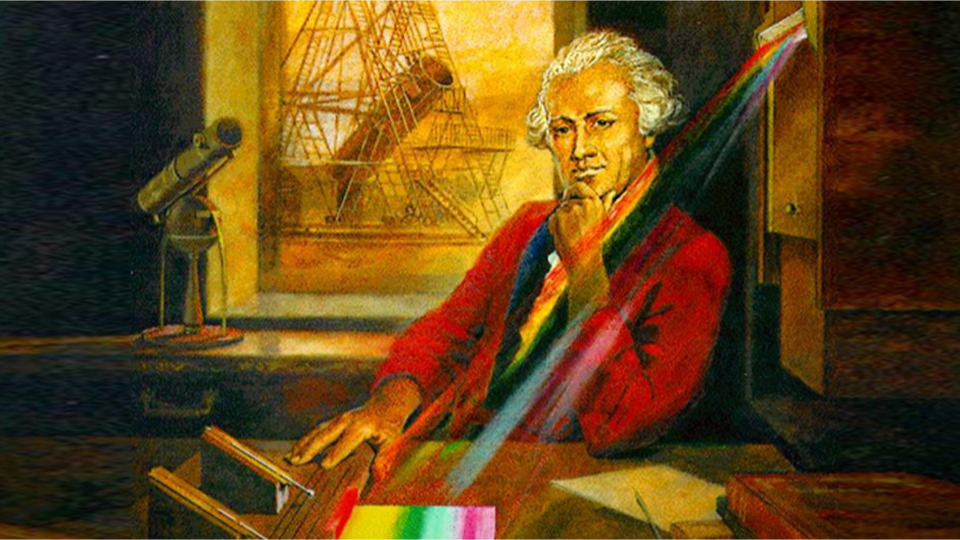

These are the contributions we’re most aware of, but it’s some of the side discoveries I find most amazing. Herschel discovered infrared radiation accidentally by passing sunlight through a prism and holding a thermometer just beyond the red end of the visible spectrum. This thermometer was meant to be a control to measure the ambient air temperature in the room. He was shocked when it showed a higher temperature than the visible spectrum. Further experimentation led to Herschel’s conclusion that there must be an invisible form of light beyond the visible spectrum.

Between his music, and his astronomy, Herschel was also a family man, and after his parents passed he took in his spinster sister.

Caroline Herschel: The first woman paid as an astronomer

Caroline Herschel is perhaps unfairly remembered as William’s grouchy younger sister and constant assistant. Originally, astronomy wasn’t her thing – When she moved from her family’s estate in Hanover to join William in England she originally gained notoriety as one of the most amazing soprano singers in the City of Bath. It was after her brother left music and began running most of his living through building telescopes that she began to become his assistant. Eventually his passion became hers, and she became quite competitive in her ability to find things in the sky, And she became the discoverer of 8 comets and a number of nebulae. When her brother married and began to spend more and more time traveling and with his family she mourned the loss of her dear brother by throwing herself into her work, and after his death she continued on, working with his son John. She’s actually the first woman to have ever received pay as a scientist when she was appointed as Williams assistant, earning 50 pounds a month. Even today, her eight comets in a single lifetime is an impressive accomplishment.

It’s easy to see how a wealthy composer could afford the equipment and time needed to build massive telescopes, and make massive discoveries, and let’s face it, most of us will never have that kind of wealth.

This is where it’s important to remember that the sky belongs to all of us, and all of us can make contributions.

COOP: 300+ years of community weather data

In the modern era, it’s thought the first citizen scientists were probably American Colonialists who recorded the weather. From John Campanius Holm recording storms in the mid-1600s, to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin tracking the weather during the founding of America, these men were united in a single purpose: They were trying to understand meteorology by recording enough data that when all their data, and all the data of the people they inspired to help, was all put together, maybe some sort of a pattern – an understanding of when and where storms will hit – could be found in their records.

It was Thomas Jefferson who first envisioned a network of weather observers. According to the National Weather Service, Jefferson recruited volunteer weather observers in six states including Virginia, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New York and North Carolina. It was on the foundations of this work that in 1849, the Smithsonian Institute set up a system for receiving weather data. By 1990, the number of observers had grown to 10,000 stations. This system still exists in the form of the Cooperative Observer Program, and is used by the National Weather Service too. In 2010 there were over 12,000 stations in the network, but today it’s shrunk to just 8700 volunteers per the NOAA website.

AAVSO: 100+ years of variable stars

Another elder community science organization that has stood the test of time is the American Association of Variable Star Observers or AAVSO, which is actually an international organization with an out-of-date name.

In 1882, Harvard College Observatory Director Edward Pickering published “A Plan for Securing Observations of the Variable Stars” in which he proposed enlisting the help of volunteer observers. As has so often happened, willing observers stepped forward to accept his offer of collaboration. Three of these men — Seth C. Chandler, a skilled mathematician; Edwin F. Sawyer, a bank clerk; and Paul S. Yendell– a man who worked as a store clerk, soldier, bank clerk, and draftsman — were all leader in the volunteer effort to recording the changing brightnesses of variable stars with 1000s of observations and a libraries worth of publications. Their efforts paved the way for William Olcott to form the AAVSO in 1911. The work done by these observers has always included observations made by the unaided eye. It takes no equipment to step into your driveway and check if a list of stars has either gone nova or dipped out of view as it is eclipsed. The human eye can even do good comparisons between stars of known brightnesses to allow it to measure changing brightnesses with sufficient precision to produce scientifically useful data for objects like pulsating red variables.

But let’s face it, it’s a whole lot more satisfying to be out there with a telescope and digital camera and not all of us can afford those.

And this is where our new age of high speed internet and massive catalogues of online data have radically changed how volunteers engage in space related sciences.