Using data from the fabulous Gaia mission, researchers have detected four new brown dwarfs as well as several other unusual companions to 25 stars in the Milky Way. Plus, Yellowstone, Earth’s magnetic field, hot Jupiters, and a review of the first episode of The Orville: New Horizons.

Podcast

Show Notes

Mapping Yellowstone’s hydrothermal explosions

- GSA press release

- “The dynamic floor of Yellowstone Lake, Wyoming, USA: The last 14 k.y. of hydrothermal explosions, venting, doming, and faulting,” L.A. Morgan et al., 2022 June 7, GSA Bulletin

Long live the Fernanda tortoise

- Newcastle University press release

- “The Galapagos giant tortoise Chelonoidis phantasticus is not extinct,” Evelyn L. Jensen et al., 2022 June 9, Communications Biology

Magnetic poles not getting ready to flip

- Lund University press release

- “Recurrent ancient geomagnetic field anomalies shed light on future evolution of the South Atlantic Anomaly,” Andreas Nilsson, Neil Suttie, Joseph S. Stoner, and Raimund Muscheler, 2022 June 6, PNAS

Hot Jupiters form in all sorts of ways

- JHU press release

- “Evidence for the Late Arrival of Hot Jupiters in Systems with High Host-star Obliquities,” Jacob H. Hamer and Kevin C. Schlaufman, to be published in The Astronomical Journal (preprint on arxiv.org)

Four new brown dwarfs found in Gaia data

- University of Bern press release

- “Results from The COPAINS Pilot Survey: four new BDs and a high companion detection rate for accelerating stars,” M Bonavita et al., 2022 May 10, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Hidden pockets of gems

- NASA Goddard image release

Transcript

Next week is a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, and we are going to have wall-to-wall astronomy news in volumes that are going to make it hard to pick which stories to cover.

Is that why there is so little astronomy news today, and we’re talking about the Earth a lot?

Yes. Yes, it is. We’re also talking about other planets. Technically, planets aren’t astronomy.

Fair. And planets do get their own conferences at other points in the year. Planets and things that occupy our planet — I’m ok with this set of stories.

Me, too. We even get to cover my favorite geology place: Yellowstone

And we have a review of The Orville’s latest season!

All of this and more, right here on the Daily Space.

I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay

And I am your host Erik Madaus.

And we’re here to put science in your brain.

There’s always talk on social media when a news alert or article about Yellowstone comes out. People have a tendency to feel anxiety that this giant caldera is overdue for an eruption, and those eruptions tend to be devastating. But the likelihood that it will erupt on any given day is very, very small.

However, volcanic eruptions are not the only natural hazard at Yellowstone. Even more common are hydrothermal eruptions, which have a less far-reaching impact but can cause local damage. And while caldera eruptions occur on the order of hundreds of thousands of years, larger hydrothermal eruptions occur on the scale of thousands of years. That timescale is still not enough to worry about, but the timing and impact are something we need to understand, and scientists just haven’t spent a lot of time studying the effects. Until now.

A new study in the Geological Society of American Bulletin analyzes cores taken from under Yellowstone Lake in a pair of known craters: Mary Bay and Elliot’s craters. The Mary Bay explosion occurred 13,000 years ago, resulted in a 2.5-kilometer-wide crater, and while the effects on land had been previously studied, the extent of the crater and deposits were not known. As for Elliot’s crater, that explosion occurred 8,000 years ago and left a 700-meter crater, completely submerged under the lake.

Several discoveries from this research were especially interesting. One, the deposits from these eruptions were more broadly distributed both underwater and on land than previously thought. Two, the Mary Bay explosion was caused by a seismic event that dropped the lake level 14 meters and resulted in a tsunami. And three, the cores revealed smaller deposits from previously unknown, more recent hydrothermal explosions.

This research was led by Lisa Morgan.

This is a space show, and while our Earth is definitely a planet, we try to avoid talking about life except when it helps us directly understand our planet. We’ve brought you tree rings and clam shells that record the geologic ages and fossils recording asteroid impacts.

But sometimes – especially when a new Jurassic Park movie is coming out – it is important to remind everyone that life can find a way.

Note: We are not sponsored by Jurassic Park, but we could be.

The geology of our world slowly changes over time. New islands rise up from the sea; new mountains rise up from the planes. Over time, plants and animals will migrate into these environments and both change the environment and adapt to what is around them. Over time, the plants and animals in these isolated locations will diverge from the populations their ancestors came from. In my fish tank, I have two tiny fish with the exact same body shape — one is stripy and the other spotty. They are from neighboring lakes in Indonesia, and time gave them distinctive looks. Looking around the world, we see the pygmy elephant on Sumatra and the pygmy sloth of the Isla Escudo de Veraguas.

But where many species get smaller, sometimes we also see things get bigger. Such is the case with the many varieties of Galapagos tortoise. And it turns out, sometimes, even a giant tortoise can be hiding.

Back in 1906, a giant tortoise was collected from Fernandina Island in the Galapagos. This was a pretty unique tortoise and, unfortunately, was thought to be one of the last of its kind. For the last hundred years, folks thought this kind of tortoise was extinct, but in 2019, a large female was found on the island – which they named Fernanda – and genetic testing revealed that Fernanda is of the same species as that 1906 specimen. Fernanda is abnormally small, and her age is estimated to be well over fifty, but an exact age wasn’t possible to determine. It’s possible she was just a hatchling when the last adult of her kind went extinct.

Researchers on the island have found evidence of at least a couple of other turtles – maybe two to three – also living on the island. According to researcher Evelyn Jensen: What comes next for the species depends on whether any other living individuals can be found. If there are more Fernandina tortoises, then a breeding program could start to bolster the population. We hope that Fernanda is not the ‘ending’ of her species.

And we here at the Daily Space also hope there will be many more tortoises in a growing population for tortoise generations to come.

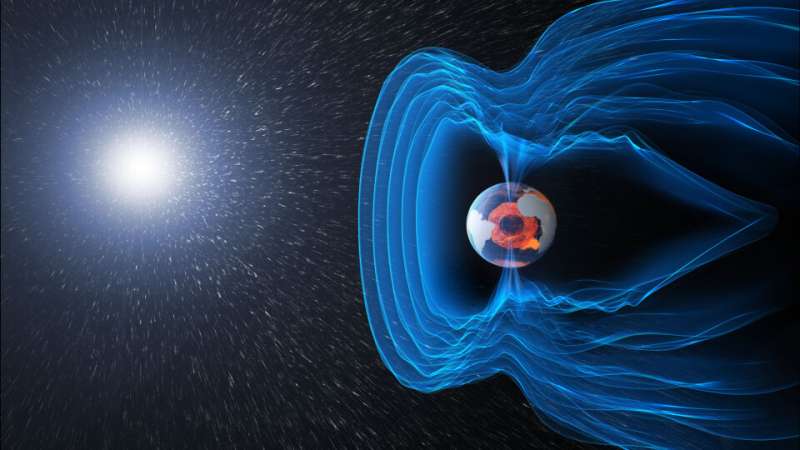

The Earth’s magnetic field is what keeps the Sun’s hazardous radiation and high-energy particles from causing problems to the biosphere, such as cancer or damaging the electrical grid. The field is generated by the rotation of Earth’s iron-rich molten outer core around the solid inner core. The magnetic field flows around the Earth from bottom to top, concentrating at these locations. These are called the poles, and on Earth, our magnetic field current flows from the North Pole to the South Pole.

Your everyday magnet you might use in science class has two poles as well. Venus and Mars are thought to have had magnetic fields in the same way but no longer do. Jupiter’s moon, Ganymede, is the only other rocky body in our solar system with a magnetic field similar to Earth’s.

Interestingly, the Earth’s poles have flipped many many times over the fullness of geology history – meaning the field lines flow in the opposite direction, in this case from South to North. We know this because the orientation of the poles is preserved in magnetic basalts produced at ocean floor spreading ridges. As you head away from these ridges, the rocks get older, and the polarity changes back and forth. Usually, the polarity changes every two hundred thousand years or so, and scientists are monitoring the start of the next reversal. Or maybe not, according to new research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

The South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) is another key thing to understand about the Earth’s magnetic field. It’s an area of weakness in the magnetic field centered off the coast of South America that causes satellites in Low Earth Orbit to have problems if they pass through it.

Now, researchers have combined several different methods to make a history of the Earth’s entire magnetic field in direction and intensity over the last nine thousand years. These methods included analyzing old, fired pottery, the previously mentioned volcanic rocks, and sediments. And it turns out that human artifacts can tell us more than just how people lived in the past.

All of this data was used to create a model of the magnetic fields, and according to one of the researchers, Andreas Nilsson, the model “predict[s] that the South Atlantic Anomaly will probably disappear within the next 300 years and that Earth is not heading towards a polarity reversal”.

So the South Atlantic Anomaly is just the most recent magnetic phenomenon in a long history of ones, and the poles won’t be flipping anytime soon.

As a side note, this work is also helping archeologists perform more accurate dating of artifacts. Some methods for determining the ages of ancient objects involve using the magnetic field, and by comparing the real magnetic field to the model, they can improve the model.

And now it’s time for planetary science.

Next week is this year’s American Astronomical Society conference, and we’ve been struggling to find press releases as universities and research groups hold onto their stories until then. Luckily, some previews are trickling out, so we’re not completely without news.

In new research to be presented fully at the conference on June 13 and published in The Astronomical Journal, astronomers from Johns Hopkins University have measured the relative ages of hot Jupiters using Gaia data. I love that mission. I really do.

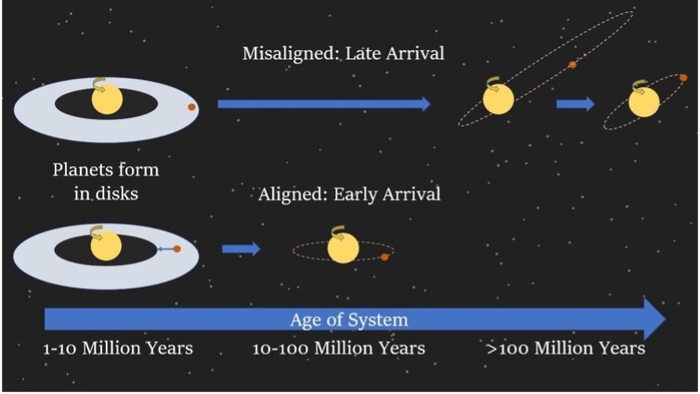

Hot Jupiters, of course, are Jupiter and larger-sized planets that orbit close in to their stars, reaching surface temperatures of thousands of degrees Celsius. Planetary formation theories have been trying to understand just how these planets came to exist, and their mere existence has really forced us to change those theories. That’s how science is supposed to work, so this is a good – albeit frustrating – problem to have.

When these planets were first discovered over twenty years ago, the prevailing theory of their formation said they formed that close in and then migrated farther out over time to reach positions like that of our own Jupiter. Or vice versa – forming farther out and migrating inward – and causing violent changes to the inner regions of stellar systems. And now, using all that precision Gaia data, astronomers have found that the answer is both. And then some.

Gaia’s data was used to determine the velocities – that is speed and direction – of the parent stars in several systems. From there, the age of the star can be determined, as stars born together move similarly to one another at the beginning of their lives. Over time, the velocities changes, and the planets in the system shift accordingly but not necessarily as quickly. And that helped us understand just how hot Jupiters evolve… sort of. Lead researcher and graduate student Jacob Hamer explains: One [formation process] occurs quickly and produces aligned systems, and [the other] occurs over longer timescales and produces misaligned systems. My results also suggest that in some systems with less massive host stars, tidal interactions allow the hot Jupiters to realign the axis of their host star’s rotation to be aligned with their orbit.

We look forward to hearing more about this groundbreaking research next week during the conference, and we’ll be bringing you more stories as they are announced.

Hot Jupiters aren’t the only new and interesting research to come out of Gaia data, which seems to be used for just about everything these days. Now, in a new paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers have announced the discovery of four new brown dwarfs. Not only were these cold, elusive planets found but they were also directly imaged. This increases the number of known brown dwarfs by about ten percent, which is impressive and yet frustrating after three decades’ worth of searching.

Brown dwarfs are strange planets that exist somewhere on the spectrum between the largest gas giants and the smallest stars. They may have been big enough to begin deuterium fusion in their cores, but they weren’t big enough to sustain the process for very long. This is why these worlds are so hard to find – they don’t create their own internal heat, and they usually orbit at great distances from their companion stars.

This research team, led by Mariangela Bonavita, developed a new tool that could be used on stars that show signs of another object in their system, gravitationally tugging away. They selected 25 nearby stars to observe and used the Gaia spacecraft to gather data. Follow-up observations were done using the SPHERE planet-finder at the Very Large Telescope, and per the press release: …they successfully detected ten new companions with orbits ranging from that of Jupiter to beyond that of Pluto, including five low-mass stars, a white dwarf (a dense stellar remnant), and a remarkable four new brown dwarfs.

The new discoveries are impressive, and they show that combining space-based observations with ground-based facilities is a good search strategy for finding low-mass companions – even when those companions are hidden by their own lack of light.

One of the great foils of science is the ability of our world and our universe beyond to hide some of the things we are most interested in seeing. Take globular clusters as an example. These pockets of many thousands of stars are generally formed in a single burst of star formation, making the stars in each cluster all of the same age and composition, like cookies all made from the same batch of dough. Different globular clusters will each be of different ages and slightly different chemistries, and by looking at myriad globular clusters, we can get snapshots of how different mass stars and how chemistry changes that evolution.

And they are pretty.

And they are also often filled with the kinds of variable stars that allow us to measure their distances accurately. This means that over the decades, researchers have tried to use globular clusters to help us map our place in space.

It was initially assumed that since globular clusters occupy roughly a sphere around our galaxy, we could measure our position relative to the globular clusters to figure out where we are compared to the center of the galaxy. Unfortunately, just like everything else, globular clusters can get lost in the shine of other stars and blocked by the dust and gas that blocks just about everything.

Today, playing hide and seek with globular clusters is a scientific sport enjoyed by many, including researchers using the Hubble Space Telescope. In a new image release, we can see the majority of red stars of the Liller 1 globular cluster shining faintly behind a crowd of bright blue stars. The blue stars are part of our galaxy’s disk.

And when found, Liller 1 had some amazing secrets to share. While the majority of globular clusters formed stars all at once, we very occasionally will find systems that appear to have had multiple epochs of star formation. Liller 1 is one of those extremely rare systems, and it appears to have formed stars both twelve billion years ago and then again one to two billion years ago. How? Well, that should be the theme of upcoming research, but for now, we have a picture, and that needs to be enough.

While pictures are awesome, let’s face it — we all like to sometimes just escape into a story. What story should or shouldn’t you escape into? This is why we do reviews.

Up next, we review the newest season of The Orville.

Review

Thursdays have always been my favorite day of the week — close enough to Friday to be excited about the coming weekend but far enough from the start of freedom to avoid the anxiety of deciding what to do on Saturday night. But as of last week, I have a new reason to look forward to Thursdays: Seth McFarlane’s The Orville has returned to Hulu under an updated name: “New Horizons.”

In case you haven’t seen this particular take on sci-fi silliness before, The Orville is a comedy science fiction show set in a futuristic space-faring world, albeit with a few scientific liberties taken. (That would be the “fiction” part.)

The show finds a comfortable home in the space between the aura of bro-humor we’re used to seeing from most of McFarlane’s other work and more dramatic notes along the lines of our favorite stretches of Star Trek. That said, it’s usually much less serious than many of the more impactful Trek episodes we know and love, but I think that lends itself well to the world we’re living in these days.

Even so, our return to orbit with the Orville drops us back into the action at a point where there is certainly some drama afoot! From prejudice and interpersonal dust-ups within the crew to the very real effects of PTSD on crew members both young and old, our return to this universe starts off with an explosive re-entry. No spoilers, I promise, but this season definitely hits the ground running, tackling some of the series’ heaviest issues so far.

Fortunately, it’s well-positioned to do so. Cultural pinch points often prove tricky to discuss with any nuance in modern media, but fiction – and science fiction in particular – has long provided a unique opportunity to do so despite the difficulty. McFarlane and the rest of the writers’ room on The Orville prove this point easily, walking the line between parody and poignancy with skill and grace.

It’s not all serious business, though. The Orville, at its heart, embraces the sillier nature of science fiction – the fanciful flight patterns that make no practical sense, the aliens who really shouldn’t fit in a space suit but do – and in the process, reminds us all of what sci-fi loves to do most: inspire us.

That inspiration doesn’t always have to come from the serious side of a story, and I’ve often found that the most effective allegories are the ones that appeal to our inner child, rather than our inner cynic. Our imaginations leap into overdrive when the boundaries of what’s possible are lifted out of our way, and this series is no slouch at clearing those obstacles.

This brings me to my overarching opinion on the return of The Orville: I’m very, very glad to see its return to my TV screen. In the midst of over two years of struggle, loss, isolation, and anxiety, it’s refreshing to sink into a little piece of escapist fiction that’s punctuated by bits and pieces of impactful social observation rather than structured entirely around them.

I’m as determined to bear witness to the struggles of the world we live in as the next person, but it can be heavy, and exhausting. The Orville examines some of the more challenging issues we experience as human beings through a lens of wit and sharp humor, softening the landing and giving us a chance to consider differing viewpoints in a safe and informal space.

That’s what I think is truly important about most science fiction — presenting information to us in a way that allows us to explore new ideas without pressure or judgment. The Orville does an excellent job packaging these ideas such that we have the space to wander around in our own biases and absorb information that helps us grow as people — as a culture.

It sounds a little silly to ascribe all that to a comedy television show, but that feels like it might be the best part of all this. The real gems of storytelling often come from unexpected places, taking us by surprise and bringing us on a journey with them. I’m delighted to join the crew of The Orville once more and venture out on that journey together.

You can catch new episodes of The Orville: New Horizons on Hulu, Thursday evenings.

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, and Gordon Dewis

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.