In an early morning announcement, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration finally revealed their first image of Sgr A*, the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. We have a special episode entirely about this amazing new image and the science behind it. And this week’s What’s Up is a total lunar eclipse.

Podcast

Show Notes

Milky Way’s black hole revealed in new image

- EHT press release

- ESO press release

- Institute of Advanced Studies press release

- MPIfR press release

- NOAJ press release

- NRAO press release

- NSF press release

- “Focus on First Sgr A* Results from the Event Horizon Telescope,” Geoffrey C. Bower et al., 2022 12 May, The Astrophysical Journal Letters

- VIDEO: Meet Sgr A*: Zooming into the black hole at the centre of our galaxy (ESO)

- VIDEO: Animation of the Stellar Orbits around the Galactic Center (UCLA Galactic Center Group)

What’s Up: Finding Sgr A*

- The Teapot guides you to the galactic center (EarthSky)

What’s Up: Total lunar eclipse

- Sunday Night’s Total Lunar Eclipse (Sky & Telescope)

- PDF: The May 15, 2022 Total Eclipse of the Moon (Andrew Fraknoi)

Transcript

Hey, Pamela. How did you start your day this morning?

I started it by live-streaming a massive multi-facility announcement from the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration about Sgr A*.

So big news today then?

The kind of news where I neither put on my makeup nor collected breakfast on my way to writing up the news at my keyboard while sitting in ‘can’t read papers fast enough’ jail.

Wow. That’s exciting. I should tell everyone how they can see Sgr A* for themselves, and remind folks about the total lunar eclipse this weekend.

All of this and more, right here on the Daily Space.

I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay.

And I am your host Beth Johnson.

And we’re here to put science in your brain.

Three hours before we were scheduled to record this episode, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration held a press conference with their latest results related to the supermassive black hole in the center of our galaxy. Seven minutes later, a slate of ten journal articles was published on these findings.

I am now going to try to summarize what I have so far been able to unpack from this trove of data, modeling, and interpretations.

First off, I want to say that these results do not fundamentally change our understanding of anything. In the most assuring of ways, what was seen matched what was expected.

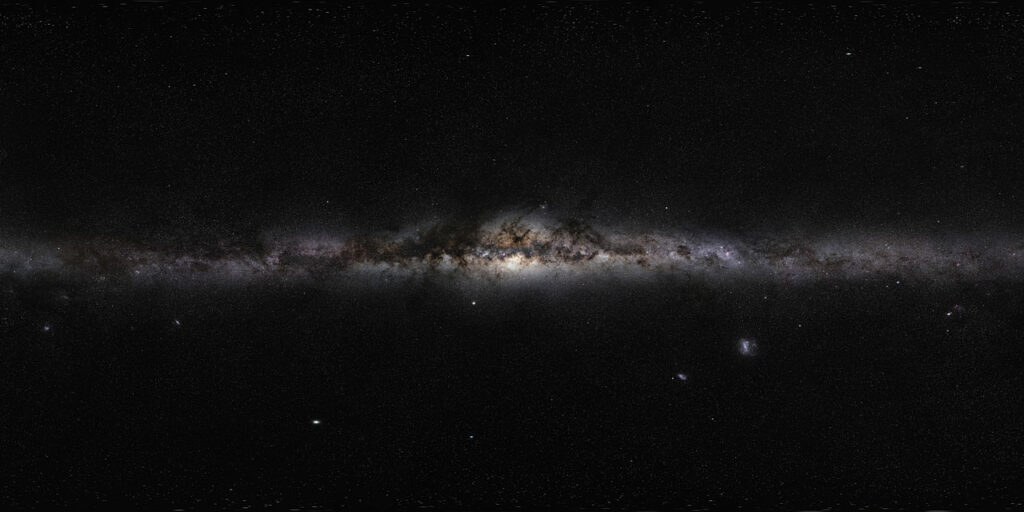

Let’s start with some background. When you go out and look at the night sky from a dark location, the sweep of the Milky Way passes through the now visible summer triangle of Cygnus, Lyra, and Aquila, and sweeps toward the equatorial constellation Sagittarius. If you have good skies and good eyes, you’ll see the band of the Milky Way thicken as it approaches Sagittarius’s teapot of stars, and that region where the Milky Way bulges out is the center of our galaxy.

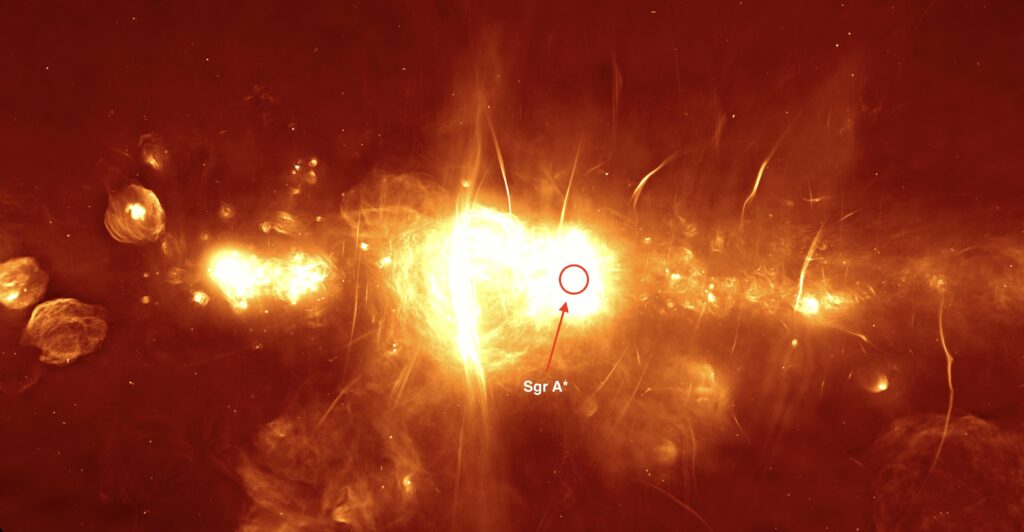

The dust and gas that fills our galaxy’s disk and the nebula and star-forming regions they create make this a stunning area to explore with binoculars, but the same features that make it beautiful also block our ability to see the center of our galaxy in the colors we can see with our eyes. Going to either much longer or much shorter wavelengths allows us to pierce through this dust, and astronomers in the last century noticed a single point from which both high energy X-rays and low energy radio waves were emitting. Following our tradition of naming things poorly, this object was cataloged as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), and over the decades, people would speculate that this monster in the Milky Way was everything from a swarm of dense objects to a singular massive black hole. As recently as the early 1990s, professors would simply sketch their favorite monster when they marked its place on an overhead sheet.

In the 1990s, researchers Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel led teams that combined high-speed (for astronomy) infrared images of the galactic center with a technique similar to lucky imaging to get super sharp images of the stars in the innermost volume of space. Over the past couple of decades, these teams have been able to capture the motions of both stars and gas in this region, demonstrating that whatever is in the center of our galaxy is so small it should be a single object, and that single object should be roughly four million solar masses in size.

Unfortunately, as the name implies, black holes are not exactly emitting light. No glowing point marks the object these stars orbit, at least not in the infrared images.

But as I mentioned, when we look in the radio, there is a glow that marks that center. In our typical images, taken with an array of telescopes that may span a large cattle-range-sized region of a desert, we can see details that are fractions of an arcsec in size. Our sky – horizon to horizon – that’s 180 degrees. A piece of hair at arms distance, that’s one arcsecond. These images? They are seeing objects tenths of an arcsecond in size, and at this resolution, the center of our galaxy is just a glowy blob.

And this is where I need to take a second to talk about optics. When you hear Apple talk about retinal displays that allow you to see the finest details your eye can resolve, they are reminding us that the human eye – when it isn’t near or farsighted – can only see objects down to a certain size. That size is related to the colors of light we are seeing in and the size of the eyeball. If you want to see more details, you need to either have a larger diameter eye or look in shorter wavelengths of light. Basically, Superman’s eyes will see a whole lot more detail in X-ray than in normal colors, and your typical anime character will be able to see finer details than your typical Disney princess.

We only have the capacity to build telescopes that are so big. For optical telescopes, we max out around ten meters at the moment, and telescopes that work in X-rays and other shorter wavelengths have to be put above our atmosphere and are much smaller. This means we can’t just use shorter wavelengths to get better images of Sgr A*. Instead, we have to use larger telescopes, and in this case, I mean using many telescopes to make a single massive scope that views the universe in light roughly just one millimeter in wavelength.

With radio telescopes, it is possible to digitally combine signals from multiple dishes to create a networked system that acts like a single telescope the size of the greatest distance between telescopes. The Event Horizon Telescope isn’t one radio dish — it is a network of eight facilities that together have the ability to resolve details as small as a standard donut set on the surface of the Moon. This suite of telescopes was previously used to observe the massive black hole in the center of the nearby galaxy M87. Because of its size, any small details around it weren’t able to seriously mess with the image. This is like imagining a cow in a swarm of flies. Sure, you might vaguely make out some flies, but overall, the cow is super easy to see.

Our galaxy’s supermassive black hole is significantly smaller. Take a donut, put it in the center of a big old football stadium, and that difference in size is like the difference between M87’s supermassive black hole and Sgr A*. This means that a swarm of flies, well, this was more like trying in observe a dung beetle in a swarm of flies. Sure, you can see it, but it is a whole lot more challenging to get a good view with all those flies flying around.

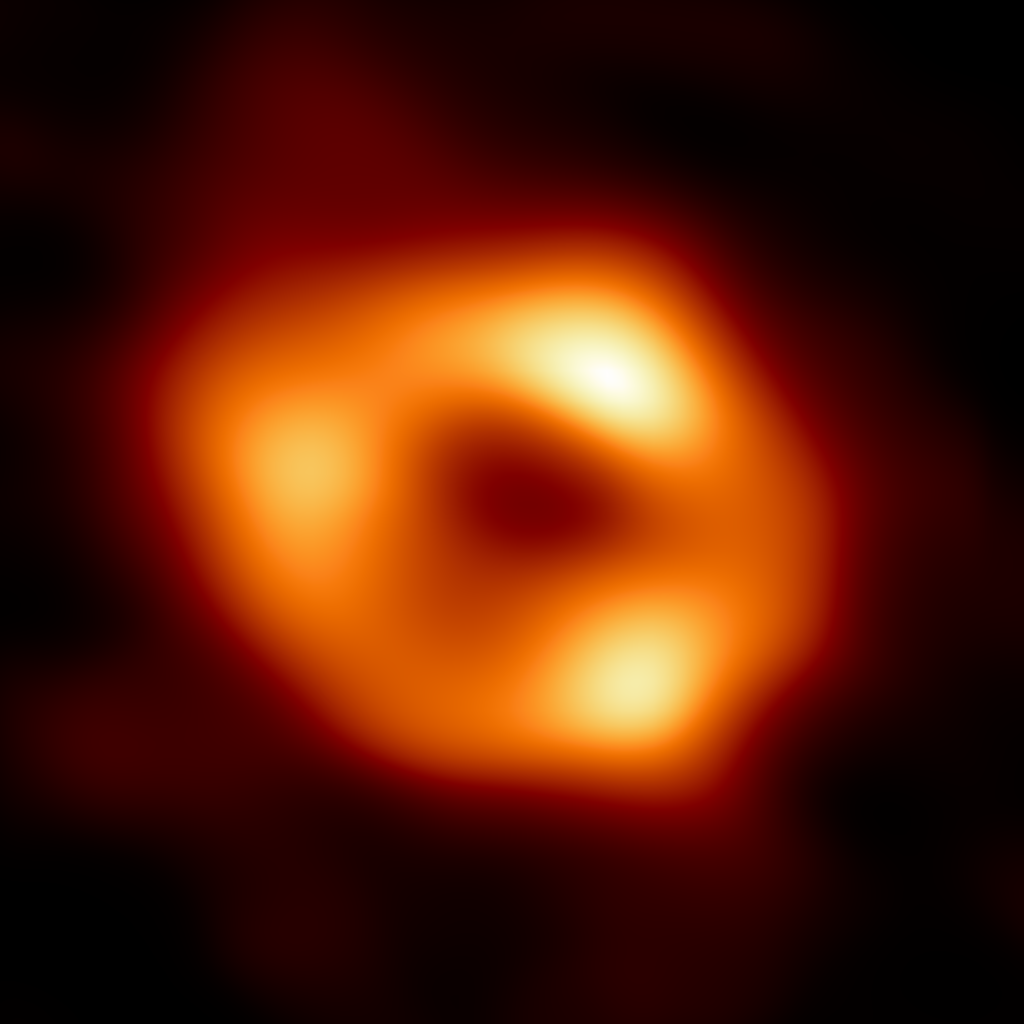

To the EHT, Sgr A* and M87* appear about the same size in their field of view, but Sgr A* is so much closer that the gas swirling around it was super difficult to deal with. But after many years of waiting, the team has finally released an image.

I have to admit, my brain wasn’t all that excited when I first saw the EHT’s image of Sgr A*. What you are seeing is the dark shadow of the supermassive black hole. That is the point from which no light shall be emitted. The glowing ring is the area of bent light and glowing gas that is right up against the event horizon. That ring, on the sky, is 52 microarcseconds across. Take a piece of hair and divide it into a million strands. Now hold up 52 pieces side by side at arm’s length. That is the size of this ring on the sky — 52 millionths of the size of a piece of hair at arm’s length. Physically, that ring is the size of Mercury’s orbit. We have now resolved the center of our galaxy to solar system-sized scales.

As a reminder, Sgr A* is 27,000 light-years away.

The moving mess of material around this galaxy made the data super hard to handle. The exposure times of the images were such that the motion blurred out details all of us desperately wanted to see. These motions, however, also helped researchers get hints at how the system is oriented.

It was this orientation that, to me, was the most insanely mind-bending part of the press conference, and it is the paper on what I’m about to say next that I’ll be reading in the most detail.

In the press conference, researchers explained that they used the black hole’s known mass and size to test models that explored a variety of spin rates and orientations of the black hole to try and find what model best fits what we’re seeing.

The best fit – as described in the presser – is a black hole that is oriented so that its north pole (using the right-hand rule) is pointed at us, and the black hole appears to rotate counterclockwise.

I have to admit to being deeply disturbed by the idea that we have a black hole’s pole – the point from which things like jets like to emanate – pointed directly at us. First of all, jets in the face are a bad thing. Second, in astronomy, we like to start from the premise that we don’t live in a special time or special place, and the idea that we just happen to be in line with the spin axis of our one and only local supermassive black hole… that feels super uncomfortable. But this is why error bars matter and details matter even more.

Looking at the paper First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. V. Testing Astrophysical Models of the Galactic Center Black Hole, I found the following specifics: The inclination of Sgr A* is within thirty degrees of pointing at us based on best fit models using eleven different constraints, of which no one model could fit all eleven constraints.

Put another way, Sgr A* is mostly face-on to us, but while it might win a game of horseshoes, there is a good chance it would miss that field goal kick, and there is lots of room for the results to be refined.

But, the idea of our black hole being flopped over on its side, like a black hole cosplaying Uranus, just makes me uncomfortable and begs the question “how the heck did it get into this predicament?”

As Bill Keel pointed out to me on Twitter, observations of radio galaxies have found that jets have a wide range of orientations compared to the disks they spray out of. It has long been figured that this mess of alignments is related to collisions. As probably happened to Uranus, something somewhere along the line gravitationally sideswiped or merged with our supermassive black hole and caused it to end up in a really weird – to me – orientation as a result. I personally am looking forward to the first paper that tries to figure out if the merger of the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus galaxy could have created this weird tilt.

Was this image worth the several years wait we’ve had since the M87* image came out? The still image, not so much. What is worth it is the dynamics that were revealed as the researchers worked so hard to try and piece together the still. In the process, they revealed dynamic structures that will, in time, give us an understanding of our supermassive black hole’s spin, orientation, and more. To see something the size of Mercury’s orbit from half a galaxy radius away? That is remarkable.

But part of me still wishes they’d let us see the first draft image that didn’t come out particularly great; the image they had back when M87* was released. Science is a process, and I wish we’d seen more of the process. Hopefully, those weird human stories behind this science-rich data set will come out.

For now, EHT has added more nodes to their radio telescope network, and they already have in hand new data that will allow them to improve on our understanding of the Supermassive Black Hole Next Door.

Want to see Sgr A* – or at least its location in the sky – for yourself? In this week’s What’s Up, Beth provides some simple instructions and also talks about the upcoming lunar eclipse.

What’s Up

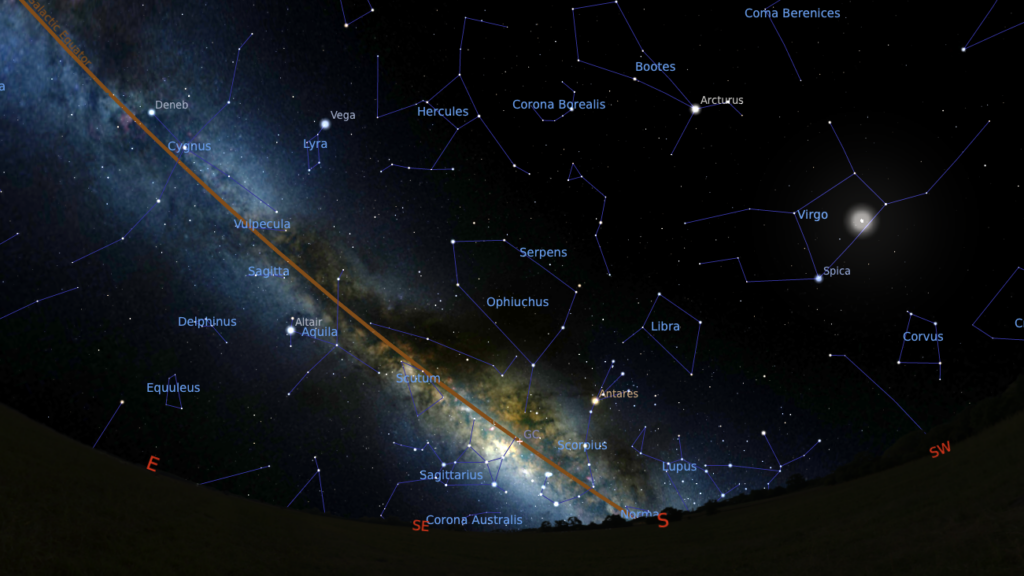

Remarkably, the news about Sgr A* came out at a time of year when you can actually go outside and look at the center of our galaxy. If you go outside after midnight, the constellation Sagittarius can be seen rising on the horizon. The exact location will vary depending on where you are, but for most of us in North America, it is in the southeast.

For me, the easiest way to find the center of the galaxy is to look for the bright summer triangle of Altair, Vega, and Deneb, and remember that Deneb’s constellation – Cygnus the Swan – is flying along the Milky Way. Arc along this faint glow of stars toward the east, look for the teapot of Sagittarius below the arc, and where the spout points up, Sgr A* is hiding. If you have binoculars, this is a truly spectacular area of the sky to wander through while relaxing in a hammock. Just remember to bring some bug spray.

There has been a drought of interesting things to look for in the night sky for most of 2022, with few exceptions. Now, finally, we have something fun to observe. This week’s What’s Up is a total lunar eclipse.

There are three types of eclipses. A solar eclipse is when the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth. A lunar eclipse is when the Earth passes between the Moon and the Sun. An apocalypse is when the Sun passes between the Earth and the Moon, at least according to Dr. Katie Mack.

On the evening of May 15, the entirety of the total lunar eclipse will be visible from most of the U.S. east of the Mississippi and all of South America. The rest of the U.S. will be able to see less of the eclipse due to the later rising of the Moon, but most people will still be able to see the peak of it.

One of the interesting features of a total lunar eclipse is the color. The Moon’s surface appears red at the peak of an eclipse because the light from the Sun has passed through the Earth’s atmosphere and been scattered so that only the redder parts hit the Moon. The degree to which this effect happens depends on the amount of the Moon eclipsed. Because this is a total eclipse, the red color should be pronounced. That is if it is not covered by clouds.

The eclipse will start at about 22:00 Central Time, with the peak happening about twelve minutes after midnight. The total eclipse ends at 00:54, and the last scraps of the shadow will be gone by 01:30 Central Time on May 16. The Moon is safe to look directly at, even during an eclipse, so feel free to turn your eyes to the sky this weekend and enjoy the show.

We’ll have links to more information, including various starting times by time zone, on our website, DailySpace.org. If you end up with clear skies and take pictures of this eclipse, we ask that you please share them on social media and tag us @cosmoquestx.

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, and Gordon Dewis

Hosted by Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.