The Decadal Survey was released earlier this month, and we take a look at some of the recommendations. Plus, this week’s What’s Up and a review of the Canon RF 16mm f/2.8 lens.

Podcast

Show Notes

2020 Decadal Survey

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

- AAS press release

- NOIRLab press release

- NRAO press release

- US astronomy’s 10-year plan is super-ambitious (Nature)

- Hunt for Alien Life Tops Next-Gen Wish List for U.S. Astronomy (Scientific American)

- Astronomers Announce Priorities for Next Decade (Sky & Telescope)

What’s Up: Leonid Meteor Shower

Transcript

Hello and welcome to the Daily Space. I am your host Dr. Pamela Gay, and we are here to put science in your brain.

Today we’re doing a special episode focusing on the 2020 Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics. Normally released every ten years, these mammoth reports are the work of hundreds of researchers who collect and distill feedback from the entire astronomical community on topics ranging from what are the most important research questions, what is the most needed instrumentation, and how do we need to work to improve our field.

In a perfect world, funding agencies like the National Science Foundation and NASA will use the findings in this report to set long-term priorities, although we have often found that presidents and Congress are likely to put their own spins on things when setting budgets.

Starting in late 2018, this decade’s report is coming out late due to problems ranging from the 35-day government shutdown that spanned from late 2018 to January 2019, and the COVID pandemic. Released November 4, this 589-page document is a lot to digest, and in this episode, I’m going to do my best to bring you highlights on how the astronomy community wants to focus its explorations of our universe for the next ten or at least eight-ish years.

Scientifically, it’s recommended that efforts focus on three broad themes, and here I quote from the report: Worlds and Suns in Context, Cosmic Ecosystems, and New Messengers and New Physics. Put another way, things are broken down into solar systems in context, the galaxies and broader universe those solar systems are in, and the weird physics that lets us study the universe with things other than light.

According to the report: The science theme of Worlds and Suns in Context captures the quest to understand the interconnected systems of stars and the worlds orbiting them, tracing them from the nascent disks of dust and gas from which they form, through the formation and evolution of the vast array of extrasolar planetary systems so wildly different than the one in which Earth resides.

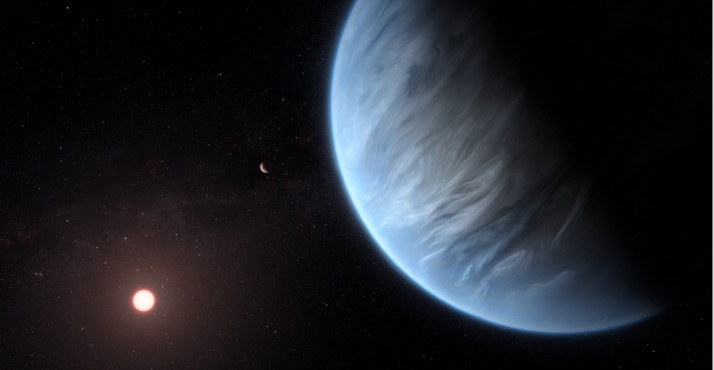

In defining how to advance this new research forward, defining pathways to habitable worlds is put front and center, with the goal of trying to discover worlds that could resemble Earth and answer the fundamental question: ‘Are we alone?’

It is time to fund research and instrumentation necessary to study planetary atmospheres to look for the biosignatures of life altering the world it lives on. This includes looking ahead to looking for planets transiting the most common stars – cool, red, M-dwarfs – using the JWST. The importance of looking for life is articulated in a way I have to share: If planets like Earth are rare, our own world becomes even more precious. If we do discover the signature of life in another planetary system, it will change our place in the universe in a way not seen since the days of Copernicus—placing Earth among a community and continuum of worlds. The coming decades will set humanity down a path to determine whether we are alone.

In looking at Cosmic Ecosystems, the Decadal Survey reminds us: A major advance in recent years has been the realization that the physical processes taking place on all scales are intimately interconnected, and that the universe and all its constituent systems are part of a constantly evolving ecosystem.

Carl Sagan once said that to build an apple pie you have to first build a universe, and the Decadal Survey reminds us that to understand our solar system, we need to understand how to build a galaxy. The priority area for research in this area is “Unveiling the Drivers of Galaxy Growth” and understanding how our universe evolved from the slight fluctuations in mass we saw after the formation of the Cosmic Microwave Background to the amazingly diverse web of structures we see today.

The survey explains that: The New Messengers and New Physics theme captures the key scientific questions associated with a broad range of inquiries, from astronomical constraints on the nature of dark matter and dark energy to the new astrophysics enabled by combined observations with particles, neutrinos, gravitational waves, and light.

And the survey goes on to say that of all these weird new things, we as a field should focus on “New Windows on the Dynamic Universe” and look at how some of the most energetic events in the universe, like the collisions of black holes and explosions of stars, can be studied not just with light but also with neutrinos and even gravitational waves. Understanding how to do it and building the infrastructure necessary to succeed at this kind of Multi-Messenger Astronomy is seen as one of the most important areas for astronomy research.

With the release of the 2020 Decadal Survey, astronomers are getting a taste of what future spacecraft and ground-based observatories are being labeled as a priority to build.

One of the most exciting parts of this Decadal Survey is the call to maintain a steady stream of smaller and midsized projects that are regularly competed and can be designed to reflect the changing needs of the field as both new technology is developed and new discoveries are made. This flexibility has been somewhat missing in the past decade, where massive items, like JWST, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the Large-aperture Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) took priority and emptied budgets.

This regular cadence also has the benefit of allowing new generations of astronomers to get opportunities to be part of new programs from beginning to end and get the experience they’ll need to be leaders on the next generation of missions. When projects like JWST take more than a generation from planning to eventual launch, you don’t really have a chance to incubate new talent that is still young when they start building their own ideas. It’s exciting to imagine a return to regular new projects coming into fruition as graduate students go from helping to build instruments to operating new systems as postdocs and proposing the next generation while still in their early career.

[Transcript unavailable.]

What’s Up

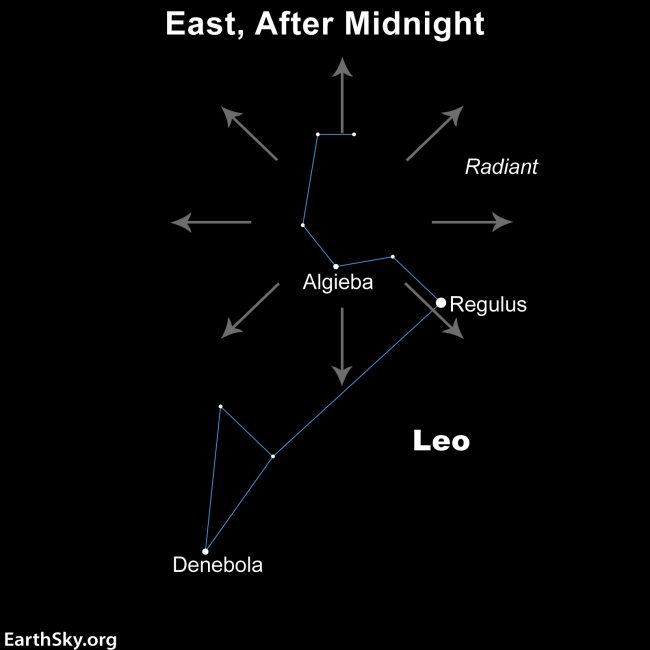

This week in What’s Up is the Leonid meteor shower. These meteors peak early next week, November 17. To find them, look for the bright star Regulus in the east low in the early morning. The radiant, or apparent point in the sky where the meteors come from, is up and to the north of Regulus in the middle of the arc of stars that appear to form the lion’s head. The source of the material for the Leonids Meteor Shower is Comet 55p/Tempel-Tuttle. We will have finding charts on our website at DailySpace.org.

Also up this week are the planets, and they won’t stay up for too much longer. Look to the south for Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, and the Moon, all in a line going up from west to east. The Moon is almost full, which will wash out most of the Leonids unfortunately, but should still provide enough contrast to see small details on the surface in a telescope. Jupiter and Saturn are unaffected by the Moon’s brightness.

So get out there, look up, and enjoy everything the sky has to offer.

Review

To wrap up this week, I’m gonna present a review of a lens I recently rented for my mirrorless Canon EOS RP, the Canon RF 16mm f/2.8 STM.

Engineering is a series of compromises, accepting some bad things to permit other good things. Nothing can be perfect for everything, and close-to-perfect things are really expensive. The Canon RF 16mm f/2.8 is marketed as “compact, versatile, speedy and affordable”, and these outline the compromises in its design. In my brief one-week rental of the lens, I encountered all of these, and my overall impression is that it’s good for what it is. You shouldn’t expect miracles; it’s not the $2400 RF 15-35mm f/2.8. The RF 16mm f/2.8 is only $300. That is very good for a camera system mainly consisting of lenses in the $1000-$2000 or more range.

The lens body of the 16mm f/2.8 itself is the same as the RF 50mm f/1.8, taking advantage of the economies of scale of that so-called standard lens’s mass production. That is part of what makes it cheap. It is small, something only possible because of the 20mm flange distance of the mirrorless RF mount, which allows larger lens elements to be placed closer to the sensor. This is an advantage over DSLRs, which require about twice the flange distance to account for the mirror box. This distance makes ultrawide lenses on DSLRs larger and more expensive, out of reach for a hobbyist.

First, two good things about the Canon RF 16mm f/2.8. The f/2.8 aperture is nice and bright and allows you to have a very short depth of field that results in beautiful bokeh and use lower ISOs for cleaner images.

Another good thing about the lens is its fast and accurate autofocus. Other RF lenses I have used with the STM-type motor have lots of trouble finding focus, particularly at close distances. I didn’t have that problem with the RF 16mm f/2.8 STM.

With the lens body, we arrive at the first major compromise of the design. The lens only has one adjustable ring on it which combines the manual focus and control rings, which acts as a third programmable dial on the camera for changing settings such as white balance, ISO, and exposure compensation, among others. The lens body only has one switch, which changes the behavior of the ring between control and focus. I don’t mind this compromise, because I don’t use the control ring or manual focus often.

The most significant compromise of the lens is in the optical design: nine elements in seven groups according to the specifications. Technically, the image quality is not good. The barrel distortion, an aberration where magnification decreases from the center of the image, is so bad it’s almost like a fisheye lens. Vignetting, where corners of the image are dark because the lens does not illuminate them, is also not great. The ability to turn off in-camera corrections is disabled both for raw images, JPEGs, and in Canon’s official software because of this.

If you go out of your way to open a raw file without any lens or camera corrections using third-party software you will see these problems. In-camera corrected JPEGs look fine, except in the corners, which are stretched to correct for the barrel distortion. At f/2.8, the corners of the image are soft and even show coma on point sources at the edge. This gets a little better at f/11, the diffraction limit for the sensor on the Canon EOS RP. The center of the image, most important to most photographers, is good at f/2.8.

Another compromise is that the lens does not have optical stabilization, but that’s not a big deal. Stabilization would have increased the price a lot, and the large aperture still permits short exposures to avoid blurring due to vibrations. Stabilization is more of a concern for longer focal length lenses where a tiny vibration can result in a lot of blurring in the image.

Canon also markets this lens for astrophotography, but I did not get a chance to take the one I rented out under the stars due to clouds. [Ed note: Shocked. Shocked I am.] My rental lens also did not include the Canon-made lens hood as it is currently in short supply, like many other things due to the current pandemic supply chain crunch.

Like all non-L series lenses, Canon does not include a lens hood with the RF 16mm f/2.8. Hoods are important for ultrawide lenses to effectively control flare, but I didn’t have any problems without one. In general, I don’t use Canon-made hoods. Third-party lens hoods are just as good for a small fraction of the price of the official ones.

I’m going to conclude my review with one more good thing about the Canon RF 16mm f/2.8. It has a higher than average reproduction ratio of .25x, meaning that you can fill the frame with something 144-mm wide at the minimum focus distance of 13 centimeters. 1x magnification is defined as filling the frame with something the size of the sensor, or 36 millimeters wide for a full-frame camera like the RP. While not a real macro lens, having that magnification on an ultrawide lens is novel and is a useful feature for closeups, which is what I like using an ultrawide lens for.

Overall I was happy with the RF 16mm f/2.8, but it’s kind of a specialized lens that most people probably won’t need to have but could buy with little justification because of its low price. At $300, it’s very affordable and has decent image quality, especially with camera-corrected JPEGs. It’s not a lens aimed at professionals and doesn’t try to be.

If you want to purchase one after listening to this review, you can do so from Amazon using our affiliate link which will be in the show notes for this episode.

This has been the Daily Space.

You can find more information on all our stories, including images, at DailySpace.org. As always, we’re here thanks to the donations of people like you. If you like our content, please consider joining our Patreon at Patreon.com/CosmoQuestX.

Credits

Written by Pamela Gay and Erik Madaus

Hosted by Pamela Gay and Erik Madaus

Audio and Video Editing by Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.