This week we present more Starlink launches, another Chinese launch, the test launch and landing of SN15, and the re-entry of the Long March 5B core stage that failed its deorbit burn last week. Plus, this week in rocket history, we look back at the launch of Alan Shepard and Freedom 7 on May 5th, 1961.

Media

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

There were two Starlink launches this week. The first was on May 4 at 19:01 UTC. Starlink L25 launched on Booster 1049 from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Booster 1049 was on its 9th flight, and successfully landed on the droneship Of Course I Still Love You. Both fairings were recovered.

And the second launch occurred five days later on May 9th at 06:42 UTC. Starlink L27 launched on the record tenth flight of Booster 1051 from SLC-40 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, also in Florida. It successfully landed on the drone ship Just Read The Instructions. Both fairings had previously flown on the GPS III SV4 mission and were successfully recovered.

This brings the total number of Starlink satellites launched into orbit to 1,625. Between the two of them, B1049 and B1051 have launched 720 Starlink satellites, almost half of the operational constellation and 260 tons of total mass inserted into orbit including the other missions the boosters launched.

SpaceX’s stated goal has been to use a first stage ten times without major refurbishment, and with the launch of Starlink L27, they have now achieved this. For those of you that are curious, Booster 1051 has quite the launch pedigree, having launched Bob and Doug to the ISS on the Demo-2 mission, plus two more commercial missions and six Starlink missions. [Ed. note: Booster 1051 launched the uncrewed Demo-1, not Demo-2.]

You may notice I said Starlink L25 and L27. L26 was skipped this time. Our team believes that it needed more integration time before its next launch. There are signs it will carry rideshare payloads where non-Starlink satellites get launched with Starlink satellites. This has happened before in 2020 with the Starlink L8, 9, and 10 launches. The rideshare payload for L26 appears to be a pair of Capella Space’s commercial Synthetic Aperture Radar satellites. These satellites weigh a considerable 112kg each — that’s 56 two-liter soda bottles — and will need to be inserted into a higher orbit. A higher orbit means more fuel will need to be burned and, because fuel has mass, it’s likely that L26 will carry fewer Starlinks than the usual 60 to make up the difference.

On May 6 at 06:11 UTC, a Chinese Long March 2C launched the Yaogan-30 08 mission from the Xīchāng Satellite Launch Center in southwestern China. Not much is known about the satellites except that they are launched in groups of three and they have a suspected signals intelligence mission. They were described by their manufacturer China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation as “will be used for electromagnetic environmental detection and related technolog[y] tests.”

On May 5 at 22:25 UTC, SpaceX’s Starship SN15 vehicle, under the power of Raptor engines 54, 61, and 66, took to the sky above SpaceX’s Boca Chica Texas launch site. SN15’s launch proceeded in much the same way as the flights of SN8, 9, 10, and 11. It took off, shut off engines progressively to reduce loads, and transitioned to horizontal flight at an approximately 10-kilometer apogee. It headed back down to the Texas sand, controlling its attitude with the forward and aft flaps and the reaction control thrusters.

At about one kilometer above ground level, the vehicle relit all three of its Raptor engines, immediately shut off one, and pitched from horizontal back to vertical. Finally, with good control of its attitude and vertical speed, SN15 extended and locked its landing legs and settled down right on the edge of the landing pad. Ten minutes later it was still standing, gently puffing away. Like SN10, there was a fire at the base of the vehicle after landing, but a water jet successfully put it out.

SN15 became the first Starship vehicle to have an entirely successful no-asterisk-necessary demonstration of the full Starship landing sequence. Congratulations, SpaceX Team! You’ve worked very hard and finally succeeded. Good luck with the orbital flight.

Now on to something that actually did catch fire because it feels like everyone is talking about it.

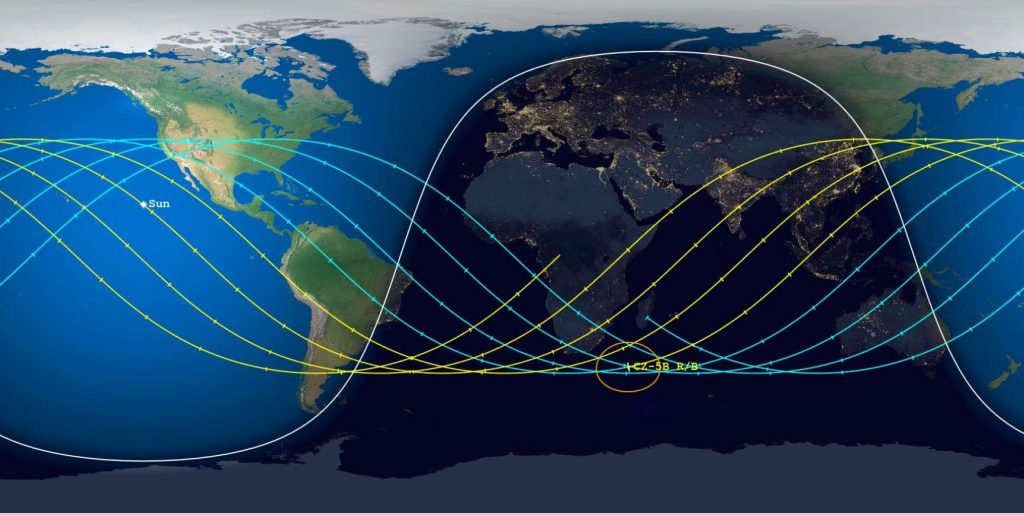

You may remember that China launched the first bit of their space station on April 29. The launch itself went fine and the core module successfully achieved orbit. What didn’t go nominally was the deorbit burn of the 22-ton, 30-meter long core rocket stage. A deorbit burn brings things like huge rocket stages down through the atmosphere to either burn up on re-entry or a planned impact in the ocean or other uninhabited space. Because that deorbit burn didn’t happen, no one knew when or where re-entry of this massive rocket stage would occur.

For reference, this was the largest uncontrolled re-entry of space debris since the decay of the Soviet Union’s Salyut 7 space station over Argentina in 1991. The size and mass of this re-entry are only equaled by the large and uncontrolled reentry of the Long March 5B Y1 core stage re-entry approximately a year ago. That reentry resulted in pieces impacting a village in the Ivory Coast.

Fortunately, this re-entry didn’t hit any inhabited areas. Instead, the core stage impacted the ocean south of Malé, the capital city of the Maldives, on May 9 at 02:24 UTC. Re-entry was observed as far west as Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, indicating the object began burning up at that point. It is not known if any pieces hit land from the reentry this past weekend.

This Week in Rocket History

This week in rocket history is once again a story from last week, but given how packed last week was, we decided to bump it to today.

On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard entered his Mercury capsule dubbed “Freedom 7” at 5:15 am local time in Cape Canaveral or 10:15 UTC. After two hours of preparation, about an hour of waiting for the clouds to clear, and almost another hour waiting for Goddard Space Center to sort out some computer issues, the Mercury Redstone Launch Vehicle finally fired and pushed Shepard and the Freedom 7 upwards.

At T+45 seconds, the capsule and the rocket began shaking violently as Shepard went supersonic, and the shaking worsened when Shepard reached the point of maximum dynamic pressure, or Max Q, at 88 seconds. Fortunately, those vibrations went away shortly afterward.

Two minutes into the flight, Shepard reported “all systems go” while he was experiencing six Gs of force! As a quick aside: to give you some idea of how much force he experienced, if you were to ride one of those rotor rides that spin around so you stick to the wall at a carnival or amusement park, you would experience about three Gs of force. Double that, and that’s what Shepard felt during his flight.

Anyway, back to his flight. At T+142, the Redstone engines shut off, and the rocket was promptly jettisoned. About ten seconds later, the capsule’s systems automatically turned it around to have its heat shield facing the direction of travel, a position known as prograde.

During its ascent, the capsule passed an altitude of 100 kilometers, the Kármán line, putting Freedom 7 officially in outer space and making Alan Shepard the first American in space! Unlike Yuri Gagarin almost a month before him, however, Shepard did not go into orbit, but rather went on a suborbital trajectory, meaning that while he did go into space, he came back down almost immediately, unlike his Soviet counterpart who stayed up there for almost 108 minutes.

While in space, Shepard had two missions.

Shepard’s primary mission was to determine whether a space capsule could be controlled manually by an astronaut; to demonstrate this, he switched off the automated flight systems that were controlling the craft and switched to manual mode. He started by trying to control each axis one at a time and letting the automated systems control the rest, but he eventually did manage to take control of all three axes.

His secondary mission was to attempt to observe the Earth using a periscope. He reported being able to see the west coast of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, the Bahamas, and even Lake Okeechobee, but he couldn’t see any cities.

At T+4 minutes and 44 seconds, Shepard put the capsule in “fly-by-wire” mode, in which the ship’s avionics are controlled not by mechanical transmissions but rather by electronic signals. He oriented the craft manually for the reentry maneuver in which the retro-rockets attached to the heat shield would fire to slow the capsule down. Shortly after reaching the peak of his suborbital trajectory at T+5 minutes and 14 seconds and an altitude of 187.5 kilometers, the rockets fired successfully and Freedom 7 began its descent.

It was then that Shepard started feeling gravitational forces kicking in again, but to Shepard’s surprise, that happened about a minute before it was supposed to according to his training. Still in fly-by-wire mode, he fought to stabilize the spacecraft as the G-forces were building up — reaching a peak of 11.6 Gs! — but as soon as the point of peak G passed, the spacecraft stabilized enough for Shepard to go back to automatic control.

Still, the capsule was falling at a much higher-than-anticipated speed. Shepard stopped relaying his instrument readings to mission control so he could listen for the deployment of the drogue chutes, which deployed successfully at T+9 minutes and 38 seconds. They slowed the craft down enough for the main chute to deploy at an altitude of three kilometers at T+10 minutes, 15 seconds.

Freedom 7 then continued parachuting down towards the North Atlantic at a speed of about 38 kilometers an hour, and at T+15:22 splashed down successfully in the Atlantic Ocean, where it was promptly recovered by the USS Lake Champlain. Safely back on the ground after four hours of waiting and nearly fifteen and a half minutes of flight, Alan Shepard, the first American in space, became a national hero.

Statistics

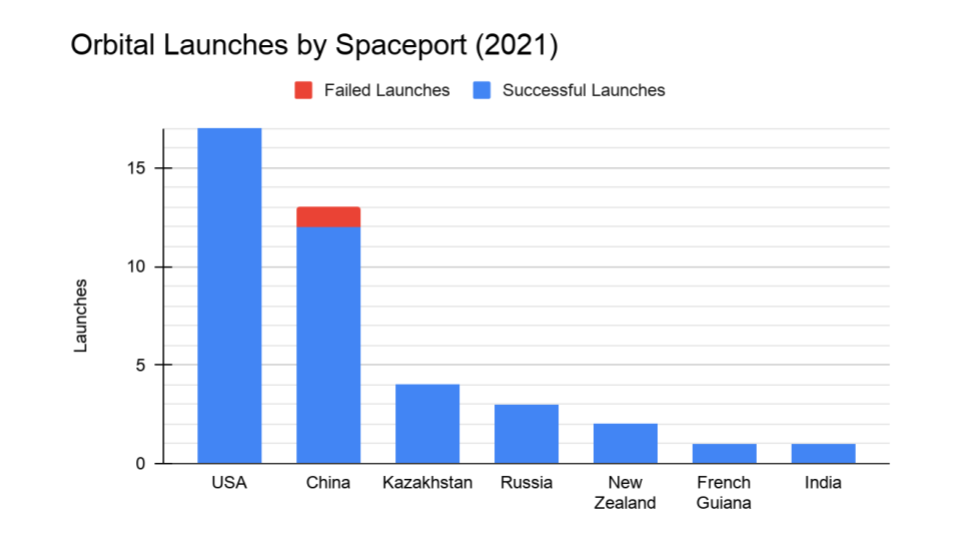

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 6: 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz, and 1 on Tianhe

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 41, including 1 failure

Total satellites from launches: 988

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 17

China: 13

Kazakhstan: 4

Russia: 3

New Zealand: 2

French Guinea: 1

India: 1

Random Space Fact

Your random space fact for this week is that during its eighth perihelion, which is a fancy way of saying closest approach to the Sun, on May 2, 2021, the Parker Solar Probe hit a top speed of 532,000 kph or 0.05% of the speed of light.

Learn More

Two More Starlink Launches Bring Total to 1,625 Satellites

- L25 discussion (Reddit)

- L27 discussion (Reddit)

- Capella info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Launch video

China Launches Another Yaogan-30 Mission

Touchdown! Starship SN15 Lands and Doesn’t Go Boom

- Starship SN15 conducts smooth test flight and nails landing (NASA Spaceflight)

- Launch and Landing video

That Long March 5B Core Stage Came Down in the Indian Ocean

- U.S. military tracking unguided re-entry of large Chinese rocket (Spaceflight Now)

- Reentry predictions for the Chinese CZ-5B rocket stage 2021-035B (SatTrackCam)

This Week in Rocket History: Alan Shepard and Freedom 7

- Launch video

- Last-Minute Qualms (NASA History)

- Shepard’s Ride (NASA History)

Random Space Fact: Parker Solar Probe

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Elad Avron, Dave Ballard, Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.