Join us for this week’s Rocket Roundup with host Annie Wilson as we look back at the launches that happened over the last week, including that fantastic, amazing, spectacular SN10 hop. Plus, we look back at Pioneer 10, which launched on March 3rd, 1972.

Media

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Today, however, is for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

First up, because we know you’re gonna ask about it, is the SN10 hop.

On Wednesday, March 3, SpaceX’s Starship SN10 vehicle took to the air from Boca Chica, Texas in a (successful) 10-kilometer test flight. The vehicle was scheduled to perform its hop earlier in the day, at 20:15 UTC, but that attempt was aborted at engine ignition. Speaking on Twitter after the abort, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk stated that the launch abort was because of a “slightly conservative high thrust limit” on the vehicle’s Raptor engines. SpaceX engineers changed the limit and fueled the vehicle for a second attempt about two hours later. The SpaceX webcast went live ten minutes before launch, with famed “norminal” SpaceX engineer John Insprucker as host.

Finally, at 23:14 UTC, SN10 ignited its three Raptor engines and took to the air, taking four minutes to reach its planned apogee. Along the way, two Raptor engines were shut down to reduce flight loads. At this early phase in testing, and with people’s houses less than three kilometers from the pad, the flights are limited to subsonic velocity. These shutdowns were punctuated by brief gushes of flame as unburnt propellant hit the hot metal of the engines, but this was expected.

At apogee, the craft hung in the air on the blue mach diamond thrust of the single Raptor engine, until that engine was shut down to begin the descent. As it began the transition to horizontal flight, the vehicle dumped excess liquid oxygen in a dramatic but planned cloud of gas.

As it descended, the vehicle controlled its attitude with the fore and aft flaps. Everything appeared to go “norminally” — a SpaceX term originating from a misspeak during a webcast — during this portion of the flight. Once it was under two kilometers in altitude, the vehicle prepared to perform its flip and landing maneuver.

At about 500 meters altitude, the vehicle relit all three of its engines, a change from the previous flight profile. All engines successfully ignited, and the leeward engine immediately shut off after the flip. This engine has the least leverage in the gimbal to flip the vehicle vertically and is only used if one of the other engines fails to ignite, which has happened before on the flights of SN8 and SN9.

After transitioning from being on its side back to being vertical for landing, it shut off the other engine and did the final landing burn with one engine. This allowed for the best control of the vehicle’s descent without having to resort to deep throttling, which complicates engine design. Unlike the Falcon 9, Starship incorporates a low thrust-to-weight ratio portion in its landing burn and one engine allows this.

It touched down harder than planned and at a slight angle, but it was still standing on the landing pad when the dust cleared. This was the first full Starship test vehicle to land successfully, after the flights of SN8 and SN9 which both exploded upon landing.

Amateur post-landing analysis of footage showed that two of the six landing legs did not latch, which would explain why SN10 was leaning just a bit after touchdown. Several days later, this was confirmed by a tweet from Elon Musk, who went on to explain the hard landing happened because the “SN10 engine was low on thrust due (probably) to partial helium ingestion from [the] fuel header tank. Impact of 10 [meters per second] crushed legs & part of skirt”, which led to an explosion eight minutes after landing.

On March 4 at 08:24 UTC, a SpaceX Falcon 9 lofted another sixty Starlink satellites to orbit from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center.

This was the eighth flight for Booster 1049, becoming only the second Falcon 9 first stage to reach this milestone. It successfully landed on the barge Of Course I Still Love You stationed 633 kilometers downrange.

After a brief coast phase, the second stage restarted. The four tension rods that kept the sixty Starlink satellites secure during ascent were released, and the newest Starlink train was deployed into orbit.

This launch was originally scheduled for February 2, but it was delayed twelve times for technical and weather reasons, including an indefinite delay for all Falcon 9 launches following the loss of Booster 1059 during landing on February 16.

Following the investigation, which concluded that the loss was due to damage to a heat shield, L-17 was rescheduled to launch on February 28. They didn’t go to space that day; the countdown was aborted at T-1:24. While a reason for the abort hasn’t been announced as of press time, we do know that it occurred during the final engine chill around the time when the cryo helium loading sequence normally ends.

Merlin engines have completed 1,174 engine-flights across 109 Falcon 9 and the three Falcon Heavies, with only three in-flight failures; on CRS-1, Starlink 6, and Starlink 18. Two-thirds of the engine failures happening on Starlink missions seem suspicious until you realize that SpaceX only uses boosters that have flown many times on the Starlink flights. The new or barely used boosters are reserved for external customers. This lets SpaceX demonstrate that the boosters are good for many uses, while not passing the risk on to paying customers. Some issues may happen, but they only negatively impact SpaceX. In any case, the primary missions of Starlink 6 and 18 were successful, deploying the satellites into the intended orbit.

This Week in Rocket History

This week in Rocket History we once again have a carryover from last week, but this time of year seems to be very popular for launches, or at least it used to be.

On March 3, 1972, at 01:49 UTC, Pioneer 10 launched on top of an Atlas-Centaur SLV-3C with a Star 37E third stage, the first time this configuration had flown. After the third stage burnout, the spacecraft was traveling at 14.4 kilometers per second — at the time it was the fastest man-made object ever to leave the Earth/Moon system. It passed the Moon’s orbit after only 11 hours, and Mars’ orbit after just 12 weeks!

Pioneer 10 had a number of firsts. It was the first spacecraft to travel to the asteroid belt, the first to make a close observation of Jupiter, and the first to leave the solar system on June 13th, 1983. Until it was outpaced by Voyager 1 in 1998, it was the farthest man-made object from Earth.

Pioneer 10 was also key to making a number of significant scientific discoveries and observations, including:

- measuring the magnetic fields in interplanetary space

- the nature of Jupiter’s magnetic field

- composition of the solar wind

As Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to pass through the asteroid belt, scientists were not actually sure how dense the belt was. Smaller asteroids could not be detected from Earth, and there was a substantial fear that millimeters-wide particles were common and passing through the belt could end up being catastrophic for the spacecraft. Shortly after, it was discovered that while much smaller particles were three times more common in the asteroid belt than they were in the space near the Earth, fragments larger than one millimeter were not to be found and were probably extremely rare.

During the Jupiter encounter, the spacecraft malfunctioned due to the high radiation environment around the planet, but most systems recovered. Only some images of Io and Jupiter itself were lost. During the encounter, the spacecraft took high-resolution pictures of Jupiter. The quality of the images it sent back was higher than anything that had been seen before of the gas giants, and the presentation of the images would later earn the Pioneer program an Emmy award!

After the Jovian encounter, Pioneer 10 went on to travel past the orbits of the rest of the outer planets, finally passing the farthest planet (which at the time was Neptune) on June 13, 1983. Its mission officially ended on March 31, 1997, but contact was maintained with the spacecraft to receive telemetry, which continued pouring in intermittently until the final signal was received on January 23, 2003.

It is currently estimated to be about 128 AU from the sun, traveling at approximately two AU a year or twelve kilometers per second.

Statistics

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 5 — 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 18, including 1 failure

Total satellites from launches: 424, with over half of those being Starlink

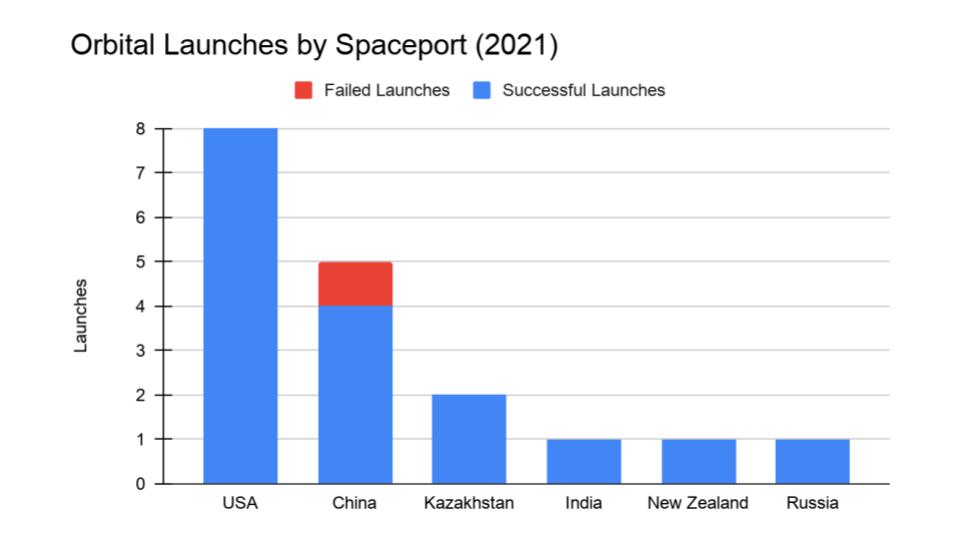

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 8

China: 5

Kazakhstan: 2

India: 1

New Zealand: 1

Russia: 1

Random Space Fact

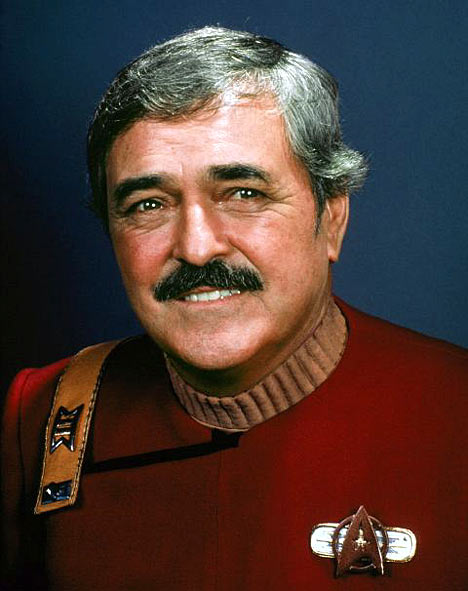

Our space fact for the week is that late James Doohan, who played Scotty on the original Star Trek, has, in fact, gone to space more than once. Well, his remains have.

As reported by The Verge, his first trip on a rocket was aboard SpaceX’s Falcon 1 Flight 3 back in 2008. Sadly, that rocket failed a few minutes after launch.

Despite official requests to bring Doohan’s ashes on the ISS having been denied, in 2008, Richard Garriott, one of the first space tourists, smuggled some of his ashes along with a laminated picture of Doohan up to the International Space Station. Without the knowledge of anyone else, except for Doohan’s family, he hid the picture and ashes under the floor of the Columbus module.

“It was completely clandestine,” Garriott told the Times of London. “His family were very pleased that the ashes made it up there but we were all disappointed we didn’t get to talk about it publicly for so long. Now enough time has passed that we can.”

And in 2012, an urn with some of his ashes flew on a SpaceX Falcon 9.

According to the Times, Doohan’s ashes have traveled some 1.7 billion miles across space, and have orbited the Earth more than 70,000 times.

James Doohan isn’t the only person whose ashes have gone to space. In 2006, the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto, were placed in an aluminum capsule on the New Horizons spacecraft, which visited Pluto in 2015.

Ad Astra James Doohan and Clyde Tombaugh.

Learn More

SpaceX’s SN10 Successfully Hops and Lands, Explodes Afterward

- Launch video (LabPadre)

Another 60 Starlink Satellites Up For SpaceX

- SpaceX announcement (archive)

- Space News article

- Countdown timeline (Spaceflight 101)

- Launch video

This Week in Rocket History: Pioneer 10

- The Pioneer Missions (NASA)

- Pioneer 10 Departs Solar System (History)

- PDF: Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958-2016 (NASA)

- Paper: On the Little‐Known Consequences of the 4 August 1972 Ultra‐Fast Coronal Mass Ejecta (Space Weather)

- Update on Pioneer 10 (University of Iowa)

- Termination of Pioneer 10’s Mission (University of Iowa)

- Spacecraft escaping the Solar System (Heavens Above)

Random Space Fact: James Doohan and Clyde Tombaugh

- The ashes of James Doohan — Scotty from Star Trek — are aboard the International Space Station (The Verge)

- A man’s cremated ashes are heading to Pluto on a space probe, and it’s the longest known post-mortem flight (Business Insider)

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Elad Avron, Dave Ballard, Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing: Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.