Media

Summary

Join us for this week’s Rocket Roundup with host Annie Wilson as we look back at the launches that happened over the last week, including one Rocket Lab and two SpaceX… wait, more Starlink? *checks notes* Yes, more Starlink.

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space. My name is Annie Wilson and most weekdays the CosmoQuest team is here putting science in your brain.

Wednesdays, however, are for Rocket Roundup. Let’s get to it, shall we?

First up, on January 20 at 07:26 UTC, Rocket Lab launched their eighteenth Electron rocket for the mission “Another One Leaves The Crust” — a play on Queen’s Another One Bites the Dust — from Launch Complex 1 on the Mahia Peninsula in New Zealand.

Before we get to the mission details, let’s check out the mission patch. It’s shaped like the pin that you’d see in Google Maps. In the foreground is the Electron rocket rising atop a red flame. In the background are green mountains and a rising orange sun. It reminds me of a sunrise over the Mahia Peninsula, where the launch site is. A black number 18 is on the right side of the patch in one of the sun rays. Rocket Lab, “Another One Leaves Crust” (the mission name), and the OHB Cosmos (the customer name) are written inside the bold black border of the patch.

This time, the Electron launched only a single payload into low Earth orbit: GMS-T, a prototype broadband communications satellite for OHB Group of Germany. Not much is known about the payload except “it will enable specific frequencies to support future services from orbit”, which suggests that the goal of the mission is to “bring in use” reserved frequencies for a planned communications satellite constellation. OHB Cosmos reported that the satellite is fully operational.

After payload separation, the kick stage performed a deorbit burn to allow it to burn up in the atmosphere quicker. No first stage recovery attempt was performed. Unusual for space missions, the launch was executed only six months after the contract was signed.

On to our next rocket launch: on January 20 at 13:02 UTC, SpaceX launched a Falcon 9 with another batch of Starlink internet satellites from LC-39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

This was a dedicated mission, so another sixty satellites were added to the mega-constellation, bringing the total number of version 1.0 satellites launched to 953 of a planned 1,440 in the first generation constellation. The launch was originally scheduled for Saturday, January 18, but was delayed several days to January 20 due to the “need for more pre-launch inspections” and poor weather at the booster recovery zone.

The launch featured the unprecedented eighth flight of booster 1051, and eight minutes after launch, it successfully landed on the drone ship Just Read The Instructions. This was also the quickest turnaround between flights of the same booster, with only 37 days, 19 hours, and 32 minutes elapsing between the seventh and eighth flights of B1051.

Both fairings had previously flown on Starlink launches and were not recovered.

For our last launch of the week, on January 24 at 15:00 UTC, SpaceX launched the Transporter 1 mission from SLC-40 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. The mission was the fifth launch of Booster 1058, which previously launched the Crew Demo-2 mission and SpaceX CRS-21, among others.

For those of you keeping score at home: Booster 1058 successfully landed on the drone ship Of Course I Still Love You positioned off of the Bahamas. Both fairings for the flight were brand new. No catch attempt was planned, but Ms Tree and Ms Chief successfully recovered both fairing halves from the water.

This particular Falcon 9 launched into a polar sun-synchronous orbit, an orbit where the satellite passes over a given location at the same local mean solar time each day. In the sixty years of launching rockets from Cape Canaveral, this is only the second rocket to do so. The first one was SAOCOM-1B back in August 2020, also on a Falcon 9. Previously, rockets were restricted from launching south due to the risk of rockets falling on the islands downrange and injuring someone.

The reason why the Falcon 9 is permitted to launch this way because of its Autonomous Flight Termination System, which enables quicker destruction of the rocket by putting the computer brains in control of the self-destruct button rather than relying on a human sitting in launch control. It may sound a little scary — allowing a rocket to blow itself up — but if something goes wrong, every second counts and the delay of receiving and processing the telemetry from the rocket and transmitting a self-destruct command might make all the difference.

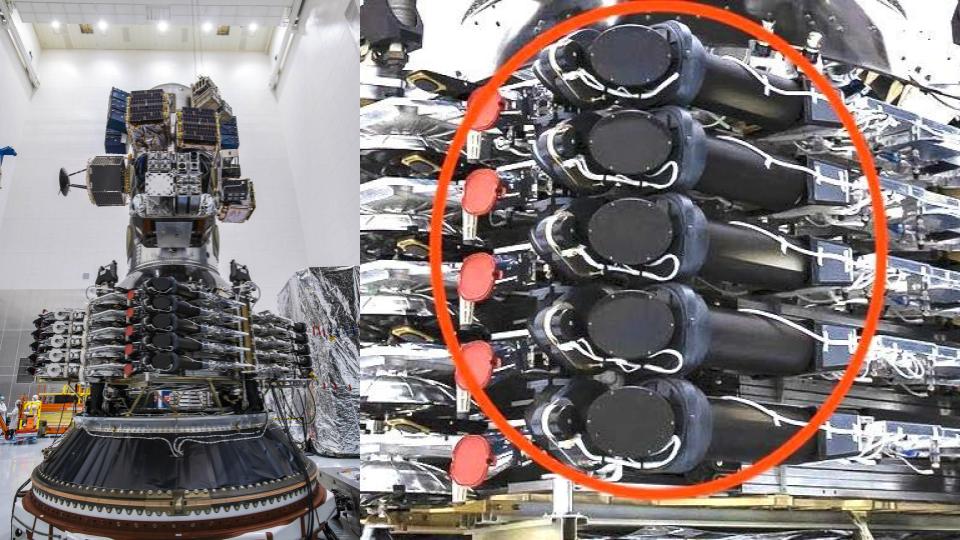

A photo of the Transporter-1 payload stack shared by a SpaceX staff photographer potentially revealed a new feature on this mini-batch of Starlinks — hardware for inter-satellite laser links.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk took to Twitter to confirm that was the case. The inter-satellite laser link is key to the Starlink system because instead of sending a packet from a customer to a satellite to a ground station to another satellite, the packet can go from customer to satellite to another satellite in the network and so on until it goes back down to Earth at the destination. This reduces the network latency. According to Musk, all of the satellites launched in 2022 will have laser links; these ten are development models.

These are the first Starlink satellites to be deployed into a polar orbit. With their laser communication links, they should be able to provide coverage farther north and south than the current Starlink constellation does by relaying data from one satellite to the next via laser until it reaches a Starlink that is over one of the ground stations. This is a prelude to providing Internet service in extreme northern and southern locations where high-speed Internet is often either not available or not affordable.

Transporter-1 carried 143 satellites into orbit, the most ever carried into space on one rocket. The previous record was 104 satellites, launched on India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle C37 mission in December 2017. 133 of the spacecraft on the Transporter-1 were commercial and government payloads, while the remaining ten were SpaceX’s own Starlink satellites.

Like the Starlinks onboard, quite a few of the satellites were additions to existing constellations, like Planet’s SuperDove, Swarm’s SpaceBEE, and Spire’s Lemur-2.

There isn’t time to talk about each and every one of the 143 satellites, so I figured I’d pick a few to share with you.

First: NASA’s V-R3x satellites. They were unique because they didn’t deploy with the rest of the satellites. Instead, they were deployed from the aft — or lower — fuel dome of the second stage. This is a common practice on the Centaur upper stage on ULA’s Atlas V, but happens infrequently on Falcon 9. The V-R3x swarm of three satellites will demonstrate autonomous radio networking and navigation.

Another notable satellite on Transporter-1 is NASA’s Pathfinder Technology Demonstrator-1 (PTD-1), which is testing a propulsion system with a water-based propellant system called Hydros developed by Tethers Unlimited of Bothell, Washington, as part of NASA’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites 35 mission.

Onboard this tiny satellite are the bits needed to communicate with the ground, the bits needed to move around in space, some solar panels, and a tank of water. According to NASA: PTD-1’s propulsion system will produce gas propellants – a mix of hydrogen and oxygen – from water, only when activated in orbit. The system applies an electric current through water to chemically separate water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen gases, in a process called electrolysis.

The CubeSat’s solar arrays harness energy from the Sun to supply the electric power needed to operate the miniature electrolysis system.

Hydrogen and oxygen are not usually allowed on CubeSats due to the danger to other payloads on a rideshare mission. However, because they start as water and are only converted to hydrogen and oxygen on orbit, it wasn’t a hazard during launch.

Developing innovative propulsion systems like these for use on CubeSats will help them maintain orbit, maneuver to avoid other objects near them in space, and hasten de-orbit, helping to reduce an increasingly cluttered space environment.

A full list of satellites on the flight is available in the show notes for this episode on Dailyspace.org.

So, earlier I mentioned that Booster 1051 recently returned from its eighth flight — the current record for a Falcon 9 first stage. Booster 1051 is now the “life leader” for the Falcon 9 fleet, which currently consists of thirteen vehicles. B1051 flew first on Demo-1 in March 2019, the uncrewed demonstration flight of Crew Dragon that paved the way for Demo-2 and Crew-1 in 2020.

It was the first Falcon 9 core to feature the upgraded Composite Overwrap Pressure Vessel 2.0 after the AMOS-6 mission exploded on the pad during a pre-launch test in September 2016 due to a failure of the original version of the pressure vessel. Booster 1051’s second flight was from SLC-4E in California, launching the Radarsat constellation for Canada in June 2019. After this, B1051 launched four Starlink missions in January 2020, April 2020, August 2020, and October 2020. In December 2020, it launched SXM-7, which went on to geostationary orbit. Its eighth flight was the most recent Starlink launch on January 20th.

To wrap things up, here’s a running tally of a few spaceflight statistics for the current year:

Toilets currently in space: 5 — 3 installed on ISS, 1 on the Crew Dragon, 1 on the Soyuz

Total 2021 orbital launch attempts: 6

Total satellites from launches: 216, which is almost a fifth of all the satellites put in orbit in 2020. From just six launches. And 65% of them from a single launch.

I keep track of orbital launches by where they launched from, also known as spaceport. Here’s that breakdown:

USA: 4

China: 1

New Zealand: 1

Your random space fact for the week: sol 3000 for the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover occurred on Mars at about 17:13 PST on January 12, 2021. A sol is a Martian day, equivalent to 24 hours 39 minutes and 35.224 seconds.

A lot of the Martian mission handlers have watches that show Martian time, and during particularly exciting parts of the mission, they will live on Martian time. This is awesome in one aspect: you get an extra 39 minutes and 35.224 seconds every day.

It is also awful because you are moving in and out of sync with everyone else in the world, which is harder than you might think.

But Mars watches, people. There are scientists with Mars watches who live on Mars time so they can more effectively talk to their spacecraft, and that is awesome.

And Curiosity has lived 3000 sols.

It still has a ways to go be the longest-lived rover, however. That record goes to the Mars Exploration Rover, Opportunity, that explored for 5,352 sols before its signal was lost in 2018 after a sunlight-blocking global dust storm.

Before we go, we want to acknowledge that on this day, January 27, 1967, the Apollo 1 crew was lost during a fire that occurred in their capsule during pre-launch tests. This accident, which killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, led to a number of changes in capsule design. Tomorrow, Beth and Pamela will discuss this accident, as well as the January 28th, 1986 loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger, and the February 1st, 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. Space is hard, and we are so grateful to the men and women who have risked their lives over the decades as humanity has worked to build a presence in space.

For now, this has been the Daily Space.

Learn More

Rocket Lab Launches “Another One Leaves the Crust”

- Rocket Lab press release

- OHB Cosmos press release

- GMS-T info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Launch video

SpaceX Launches Another 60 Starlink Satellites

SpaceX Transporter 1 Launch Breaks Rideshare Record

- SpaceFlight Now article

- Kepler 8-15 info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Flock info page (Gunter’s Space Page)

Random Space Fact: 3000 Sols for Curiosity

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory press release

Credits

Host: Annie Wilson

Writers: Dave Ballard, Gordon Dewis, Pamela Gay, Beth Johnson, Erik Madaus, Ally Pelphrey, and Annie Wilson

Audio and Video Editing: Ally Pelphrey

Content Editing by Beth Johnson

Executive Producer: Pamela Gay

Intro and Outro music by Kevin MacLeod, https://incompetech.com/music/

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.