After 16 years of taking amazing data that has generated amazing science, the Spitzer space telescope was decommissioned. In this episode we look at its role as a part of the Great Observatories program, it’s prolonged life as JWST has been delayed. Now, astronomy is without far infrared capacity, but we have a wealth of data to keep mining.

PHOTO COURTESY NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UNIV. OF WISCONSIN

- NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope Ends Mission of Astronomical Discovery (JPL)

- Spitzer Space Telescope (NASA)

- For Hottest Planet, a Major Meltdown, Study Shows (JPL)

- NASA Telescope Finds Elusive Buckyballs in Space for First Time (JPL)

- NASA’s Spitzer Sees the Light of Alien ‘Super Earth’ (JPL)

- Spitzer’s SPLASH Project Dives Deep for Galaxies (JPL)

- Hubble Find “Twins” of Eta Carinae in Other Galaxies (Hubblesite)

- Spitzer Maps Climate Patterns on a Super-Earth (JPL)

Because 2020 only takes and never gives, I’m here to bring you the news that yesterday, after more than 16 years of amazing science, the Spitzer Space Telescope was decommissioned.

Launched in 2003, this mission started with liquid Helium coolant that allowed it to see far into the infrared, revealing in high resolution aspects of the sky that had only been hinted at by the earlier IRAS telescope (which coincidentally is the telescope that had a near miss over Pittsburgh earlier this week).

In 2009, Spitzer ran out of coolant. Up until this point, it had an imager, spectrograph, and multiband photometer that could measure brightnesses across multiple colors. Only the imaging instrument still functioned without coolant, but thanks to Spitzer’s creative orbit, the imager could be kept cool enough through passive techniques that Spitzer could keep doing science.

Like the Sun observing STEREO spacecraft, Spitzer was put into an orbit that was just different enough from Earth’s, that Spitzer has slowly lagged further and further away from our planet. This means the spacecraft only has to worry about heat from a single source – The Sun. Thanks to the vacuum of space, most of the Sun’s heat could be blocked with a Sun shield that puts the spacecraft in constant shadow.

A sunshield is the same technology that will someday be used by JWST …. we hope. While people often think of JWST as a followup to Hubble, the truth is that JWST is a followup to Spitzer. While Spitzer was a 1 m class telescope, JWST, if successful, will be a 6 m class telescope, able to see higher resolutions and fainter objects. Part of retiring Spitzer is preparing for JWST, although this mission lived far beyond what anyone could have expected. Planned as a 2.5 with the expectation that it would extend out to be a 5-6 year mission, bringing it in line with the original 2010 planned launch of JWST.

With JWST’s delays, Spitzer’s importance to the astronomical community has never slacked, but it’s batteries couldn’t live up to the scientific demands. Recently it has only been able to transmit back data for a few hours at a time. Several months ago, when JWST still locked on track for a March 2021 launch, it was decided that Spitzer would finally be allowed to retire. With the latest Government Accountability Office assessment of JWST, it looks like it is likely to be delayed again, and for the foreseeable future, astronomy is going to be without an infrared space telescope. This is particularly frustrating to the exoplanet community, which built and launched TESS assuming JWST would be able to do rapid followup, and have worked with Spitzer to great success.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/O. Krause (Steward Observatory)

Spitzer did more in its 16 years than anyone could have imagined, and as we mourn its loss, we need to also celebrate its amazing accomplishments.

Since I first started collecting press releases in 2008, I received 671 press releases mentioning Spitzer and addressing science topics ranging from comets to exoplanets, to small stars, to massive galaxies.

Spitzer’s work was done in the context of NASA’s great observatories program, which worked to make it possible for astronomers to explore the sky across the entire electromagnetic spectrum. Originally consisting of Hubble for optical / UV, Chandra for X-Rays, Compton for Gamma rays, and Spitzer for Infrared, this program has worked in concert to image target after target. While Compton died far too young, failing and deorbiting in 2000, the trio of Hubble – Spitzer – Chandra have released a myriad of multi-wavelength images. For extragalactic astronomy, these images, including studies of the whirlpool galaxy, M101, and the active galaxy M82, allow us to trace gas of all temperatures and see the detailed structure of different parts of these complex systems, allowing us to see how galactic cores, star forming regions, dust and gas, and galactic arms all interact. The drama of stars and nebula was also brought to life through this collaboration, with images of everything from supernovae remnants and star forming regions showing us just how much more dramatic the universe appears if you can see with more than just the colors visible to your eyes.

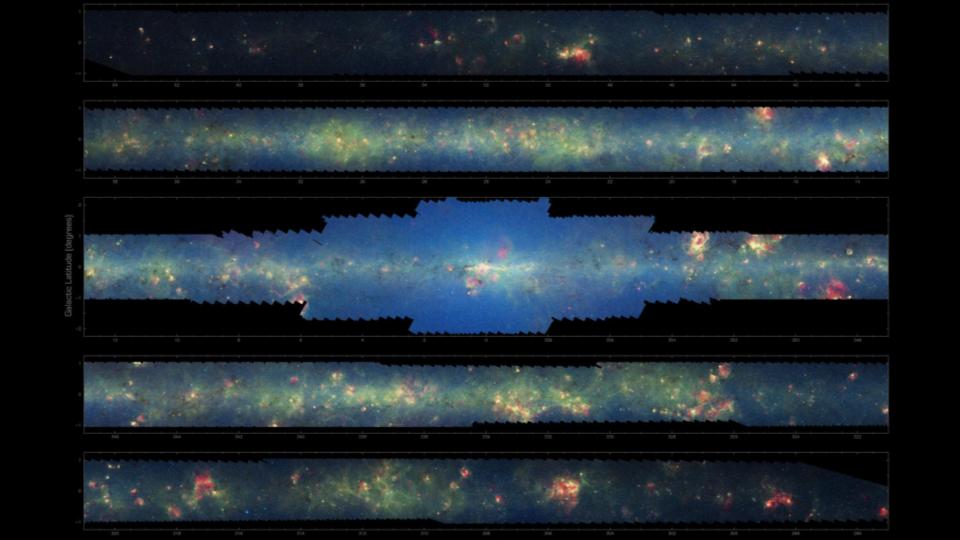

Spitzer has also proven it is an amazing workhorse in its own right. For me, the most memorable Spitzer release was a mosaic of our entire galactic disk in Infrared. This massive image was printed out in long glorious detail for display at an American Astronomical Society meeting, and since it’s 2008 release, scientists have continued to find new ways to get new science out of this wealth of pixels.

In addition to creating these massive detailed images, Spitzer has also been responsible for less photogenic data that succinctly describe the sizes and of the Trappist 1 planets, the presence of water in the atmosphere of planets including HD 209458b and K2-18b, and event the weather of HD 149026b.

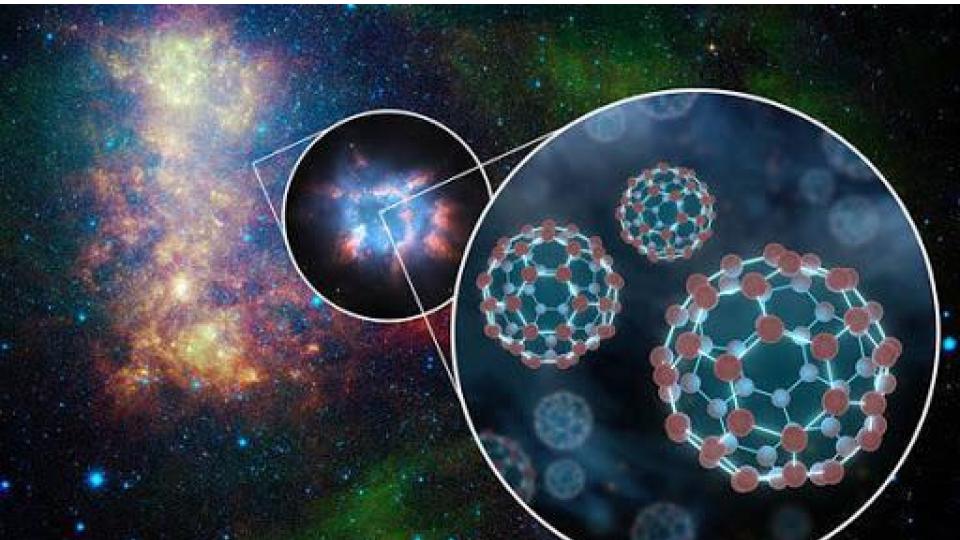

In recent years, Spitzer has particularly accelerated our understanding of solar systems, as it has not just described the details of planets, but also of their surrounds, as it has studied dust disks, giant planetary rings, and even discovered carbon buckyballs in the environment around a small hot star in the XX Ophiuchi binary system.

Put simply, Spitzer did a lot of good science; enough science to fill several seasons of Daily Space.

There are a lot of good roundups on Spitzer floating around today. Phil Plait has a great thread on Twitter, https://twitter.com/BadAstronomer/status/1223280615413305344, and Hank Green touches on Spitzer’s amazing mosaic of the milky way in his latest video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OWRz1JpVZSc&feature=youtu.be. Next Wednesday, the Weekly Space Hangout will be featuring Michael Werner and Peter Eisenhardt, two scientists who have worked on Spitzer and are the authors of the book More Things in the Heavens that discusses IR astronomy, particularly by Spitzer. If you want to learn more about Spitzer, all the resources will get you started.

<———————>

And that rounds out our show for today.Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is written by Pamela Gay, produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you. Want to become a supporter of the show? Check us out at Patreon.com/cosmoquestx

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.