This weekend SpaceX purposely exploded a Falcon 9 to test the Crew Dragon abort system and as everything went as planned, and we discuss what is next – maybe – for the SpaceX human space program. From there, we look at two new comets from other solar systems, nitrogen in comets from our solar system, and then take the promised deep dive into news about our Galaxy’s Sag A*.

As promised, today’s episode will take a deeper dive into the dynamics and content of our galaxy’s central region. Before we do that, we do have a couple of news items to highlight.

- SpaceX successfully blows up a Falcon 9 rocket in escape test launch (Cnet)

- SpaceX’s Crew Dragon returns to shore after successful abort test (photos) (Space.com)

First off, after multiple weather related delays, SpaceX was able to launch a 3-time used Falcon 9 from Kennedy Space Center’s launch pad 39A. Atop this rocket was a Crew Dragon Capsule containing two mannequins and a whole lot of sensors. This wasn’t a normal launch; this was the inflight abort test many of us have been waiting months to see. Less than 2 minutes after launch, and after sustaining Max Q, SpaceX had their Falcon 9 just… turn off. This had two effects. As planned, software onboard correctly processed sensor and system data to recognize the problem, and released the Dragon Crew Capsule and fired its Draco Engines to get it the expletive out of there. The next thing that happened was the unstable rocket proceeded, as planned, to explode in a very dramatic way. The jettisoned capsule accelerated away with a maximum acceleration of 3.4 g. This is significantly easier on the body than what astronauts experienced during a necessary abort on a Soyuz capsule in October 2018. After reaching a maximum altitude around 25 miles or 40 km, the system began its safe journey home, with all parachutes deploying as planned and a safe splash down into the ocean. This successful test prepares the way for a launch sometime this year.

In a press conference following the abort test, there was a clear attempt to maintain a single narrative between NASA administrator Jim Bridenstein and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, and Musk stated they’d agreed on messaging prior to appearing, roughly 15 minutes late, on the press conference stage. Musk made it clear that SpaceX should have hardware ready to go by the end of February or at worst early March, and should be ready for launch shortly there after. Bridenstein, on the other hand, stressed the desire for additional tests of the parachute system on the Crew Dragon, and said that NASA is going to be rethinking how to use this new hardware, and consider if they’d like to change their current plan to have a short mission to the ISS, and instead have the astronauts stay for an extended period. That latter option would require additional training, and would delay launch by an unknown amount of time. Many of us wonder why NASA didn’t provide training for both kinds of missions – long or short – already and some question if this is a delaying tactic to allow Boeing and its Atlas launched Starliner a chance to catch up in development. Bridenstein was extremely clear that NASA wants to have multiple suppliers of human space launch services, and continues to publicly back Boeing and United Launch Alliance. In December, when our Daily Space team visited Kennedy, we found that the information given during facility bus tours actually stressed these older companies and talked about how it would be Boeing that returned Americans to space from American soil. Since NASA is a government funded agency, there is complex politics behind every public message – messages often designed to keep the congress people who write the budgets happy. As we watch the similarly politically motivated actions in the following months, we will be playing close attention to see if Boeing puts their capsule through the same tests and experiences the same timeline delays as we’re seeing for SpaceX. We are a fan of a take it slow, test everything, and move forward boldly kind of approach, but we want to see fairness in how these two companies are allowed to advance their technologies.

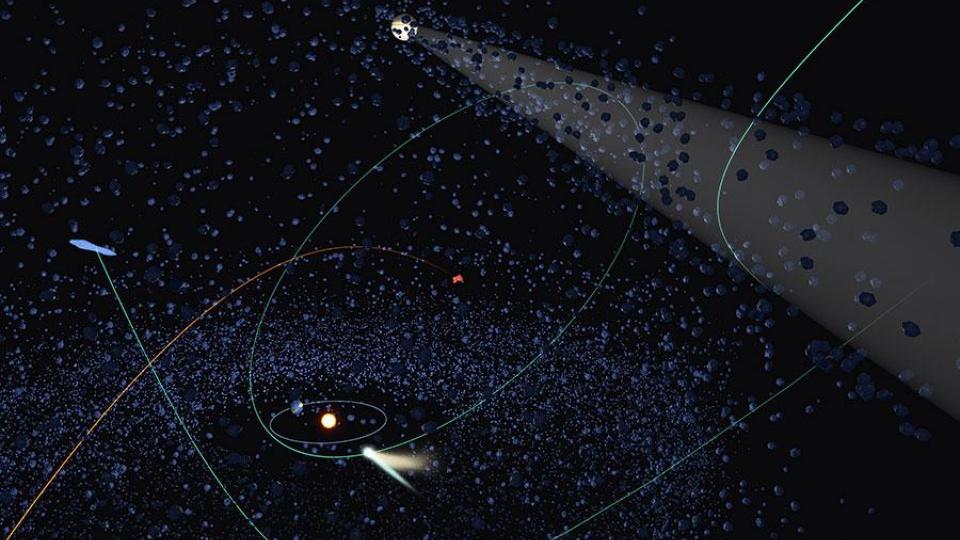

In other news, a bit further from home, a team of NAOJ researchers has published in the MNRAS the orbits of two outbound comets and determined that these comets could easily be two more alien objects caught passing through our solar system. It is also possible that these are objects from the Oort Cloud that were put on escape trajectories through some kind of an interaction or perturbation.

This has me thinking. Growing up I, and probably many of you, learned that comet orbits come in basically 4 varieties, short period, long period, parabolic, and hyperbolic, where these latter two kinds of orbits both send comets flying out of our solar system. While 2017s 1I/‘Oumuamua was the first definitively extrasolar object to be observed, what if we’ve been observing comets from other solar systems on a random basis for as many centuries as we’ve been observing comets? The rapid rate that we’ve gone from the discovery of 1I/‘Oumuamua to recognizing multiple objects of possible alien origin makes this question of particular interest and I look forward to seeing how our understanding of the origins of comets changes in the coming years.

- The salt of the comet (Unibe)

In other comet news, and building on last week’s announcement of phosphorus in comet crusts, we are now learning that comets are rich in ammonia ices that trap nitrogen into hard to measure solids. These results come from the Rosetta mission and a Bernese instrument that sampled the material around the spacecraft to directly measure chemical compositions. Earlier research looking at spectra of Halley’s comet’s coma turned up significantly less nitrogen than expected. Solid ammonia, however, wouldn’t have been measurable in that data from the Giotto mission. This new data gives us one more piece of evidence that impacting comets – and likely asteroids as well – brought with them all the building blocks of life.

And while that rounds out our news for today, we do not want to take that planned drive into the center of our Milky Way galaxy. In recent months we’ve seen a series of discoveries add nuance and detail to our understanding of the inner few parsecs our super massive black hole, Sag A*.

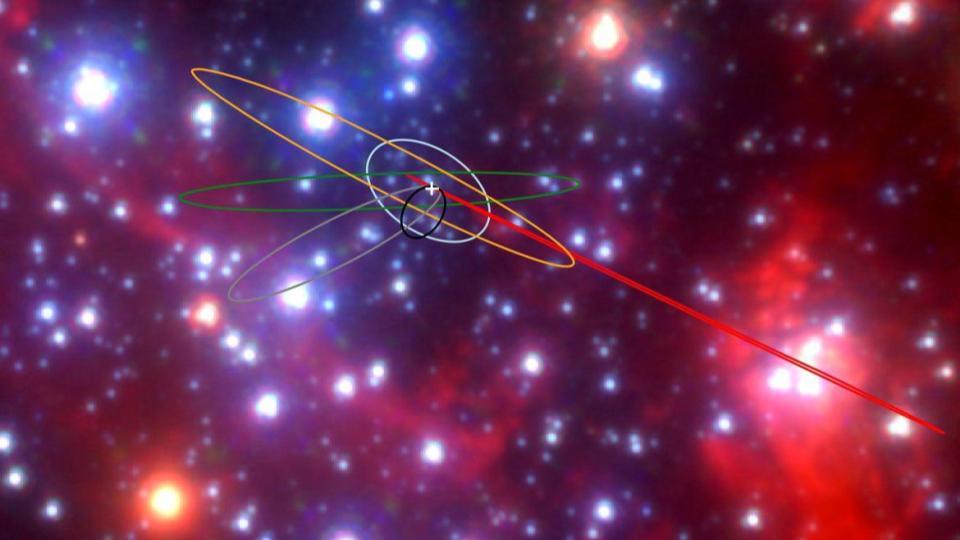

We have known since the late 1990s that our galaxy has a supermassive black hole in its core that is 4.3 million times the mass of our Sun, and is orbited by stars that get as close to this black hole as 970 astronomical units, or roughly 20 times Pluto’s distance from the Sun. This understanding comes the amazing work of UCLA’s Andrea Ghez who created a new way to use the Keck telescopes to take extraordinarily high resolution ground based images of the stars swarming Sag A*. As her team and other astronomers have followed the motions in the inner part of the Milky Way, they have revealed a cluster of young stars with ages measured in millions rather than billions of years. While this team has been able to see individual stars, they have only been able to see the largest stars, and it has been suspected that there is a large population of what are called S-Cluster stars that orbit in this inner region, with the more numerous smaller stars being beyond what our telescopes can see.

Last week this story got one new population of objects, unceremoniously called G objects, appear to be gas & dust blobs that are getting distorted during their closest passes near Sag A*. These objects can be explained as merged small binary stars, and they exist in numbers consistent with what would be seen in a star cluster with the population of large stars we see as S-cluster stars. This traces out a picture of a young star cluster forming as it plunges for whatever reason into the heart of our galaxy. This system was then dynamically stirred up by the gravity of Sag A* with stars – the massive S stars and the merged binary G objects and all the objects too small for us to see – all sent into chaotic orbits. This is a special moment in time during the short period when these massive stars are alive and easy to see. We have no idea how common this kind of a star cluster plunge takes place, and the science coming out of this is still emerging and is awesome.

And while this is all awesome, the best may be yet to come. The Event Horizon Telescope has unreleased images of Sag A*. Last April the Event Horizon team released their image of the significantly larger M87 SMBH. The smaller Sag A* has been harder to process since the material around it is comparably more obscuring. When that image comes out it will build this picture out in new ways and in new details.

And *That* rounds out this episode.

<———————>

And that rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you. Want to become a supporter of the show? Check us out at Patreon.com/cosmoquestx

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode on Twitch.tv, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you can help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let your friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.