We have so much news today, so much news we can’t neatly sum it up. Join us as we look at rare star formation in galaxy clusters, get annoyed with Starlink (as one does), celebrate new science from Cassini that maps out Titan, and finally as we learn that zero gravity is really bad for blood flow.

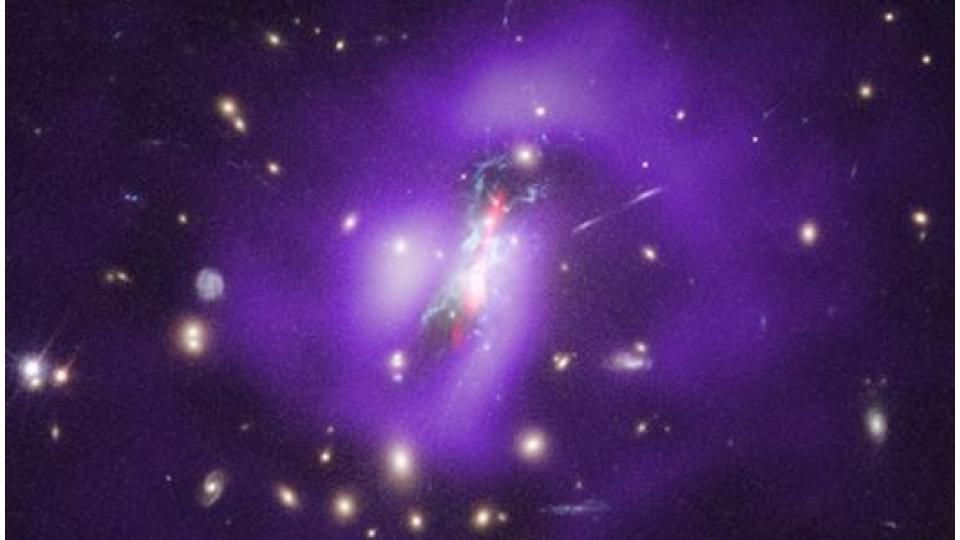

Today’s episode starts with the results of a multi-wavelength study of a distant galaxy cluster forming stars. This simple fact means that we have caught this system in that brief window of time between when the cluster has formed, and when blasts of energy from the core around the central supermassive black hole have made further star formation impossible. Black holes themselves can’t give off light, but as material flows toward a black hole, it builds up into a disk called an accretion disk, and this material can become so dense that ignites with nuclear reactions, giving off massive amounts of light. This disk, which can be filled with spiraling charged material, can also generate massive magnetic fields that power jets that stream material out of the galaxy. The pressure from this light and these jets reshapes galaxies, clearing out their inner regions and heating the system to temperatures that prevent gas and dust from gravitationally coming together to form new stars. Once this happens, star formation is over, but before… well that’s when the magic happens. When galaxies interact, as they so often do in the centers of galaxy clusters, gas and dust can get knocked out of stable orbits and driven toward the galactic centers where some of it will begin to build that deadly accretion disk while other material undergoes rapid and massive amounts of star formation.

While astronomers have long understood this is how galaxy evolution in clusters should occur, we have struggled to find a system that has a central galaxy still in this rapid star formation phase. In 2012, a team of astronomers led by Michael McDonald found indications that such an elusive system exists 5.8 billion light years from earth in the Phoenix Constellation. Newly presented observations published in the Astrophysical Journal combine data from the Hubble and Chandra space telescopes with Very Large Array radio data to trace out the distribution of hot gas, cold gas, and star-forming regions. They find this system is converting 500 solar masses of material into stars every year. This is in comparison to our own Milky Way’s average of 1 solar mass per year. At this point in the galaxy’s life cycle, the central supermassive black hole growing, and outbursts related to its accretion disk are still sporadic and just push hot material outwards where it can cool. This means that rather than killing star formation, the outbursts are currently churning gas in ways that facilitate star formation. Over time, as the black hole continues to grow, and as outbursts from the accretion disk become more turbulent the shockwaves will begin to super heat the gas and shut down star formation, making this cluster look like all the other clusters we’ve observed so far.

These observations are a great check on our understanding of galaxy evolution, and finding this rare system in the vastness of space in one heck of an awesome feat. Our intellectual hats are off to this team of observers. You can see an image of this system in all its star forming multi-wavelength glory on our website, dailyspace.org.

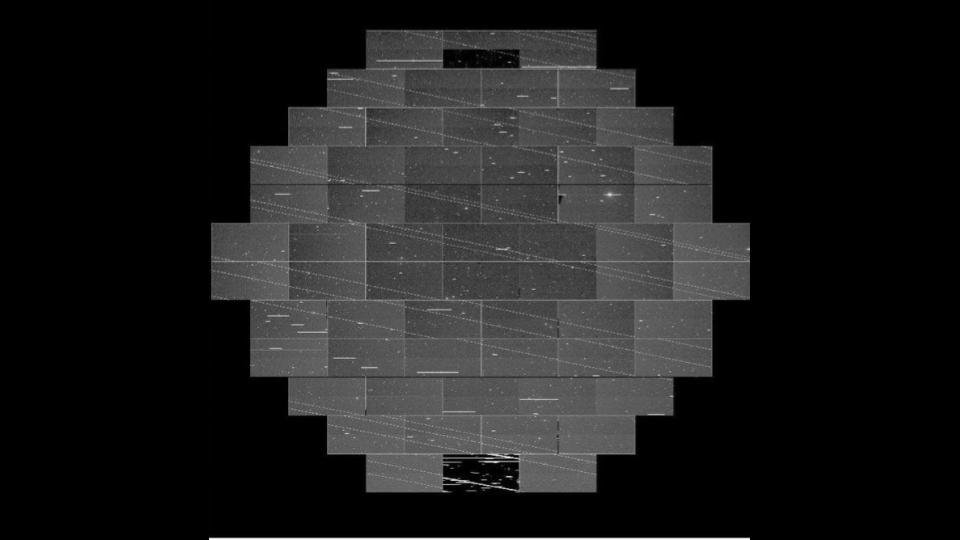

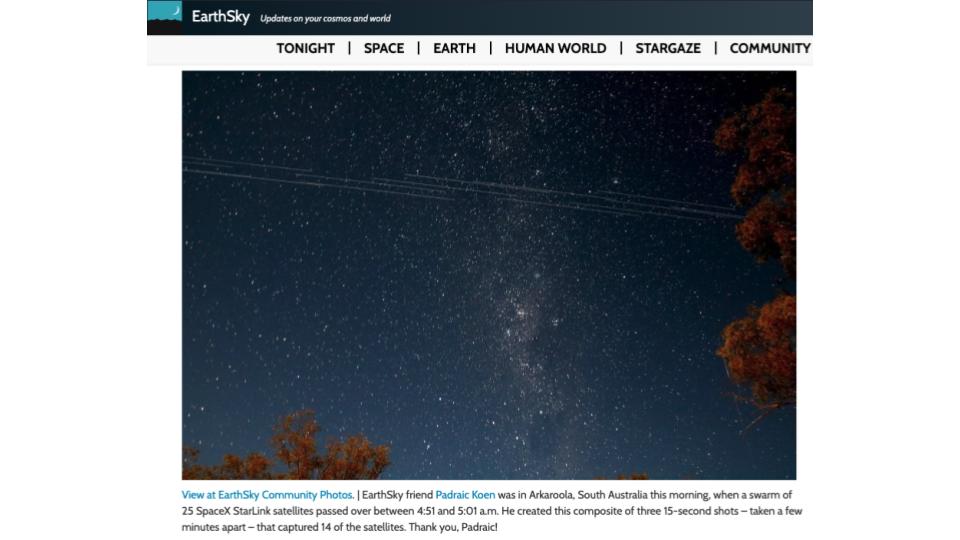

Finding and observing systems like this one is a task for survey scopes, and throughout the history of astronomy we’ve seen systems from the glass plate Palomar Sky Survey, through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and to the modern Dark Energy Camera all work to survey our sky to map out the structure and changing nature of our universe. Making these kind of studies is getting a bit more challenging, however, thanks to the proliferation of annoyingly bright satellites. SpaceX is systematically working to provide the world with low-cost internet with its Starlink constellation of satellites, but along the way it is also creating a nightmare for astronomers. Last night, Clif Johnson shared a Dark Energy Camera image that was plagued with 19 bright stripes that were created as the latest suite of Starlink’s to launch passed through the detectors’ field of view over the course of 5 minutes. While these satellite trails can be worked around by taking multiple exposures, this increases how long it takes to accomplish science goals, and eats up our limited time. The sky is only dark for so many hours each night, and the moon is only out of the way for a more limited part of that night. Having to spend longer on every field so we can effectively eliminate even more satellites … well, this will slow science while really annoying scientists. I am in favor of providing the world with low cost internet, but … well… frustrated astronomers like me are going to whinge while we try and accept that this is our new normal.

Ultimately, the solution is going to be launching more telescopes into space above the satellites of frustration. We’re not there yet, and for developing massive or experimental systems, this may never be an optimal solution.

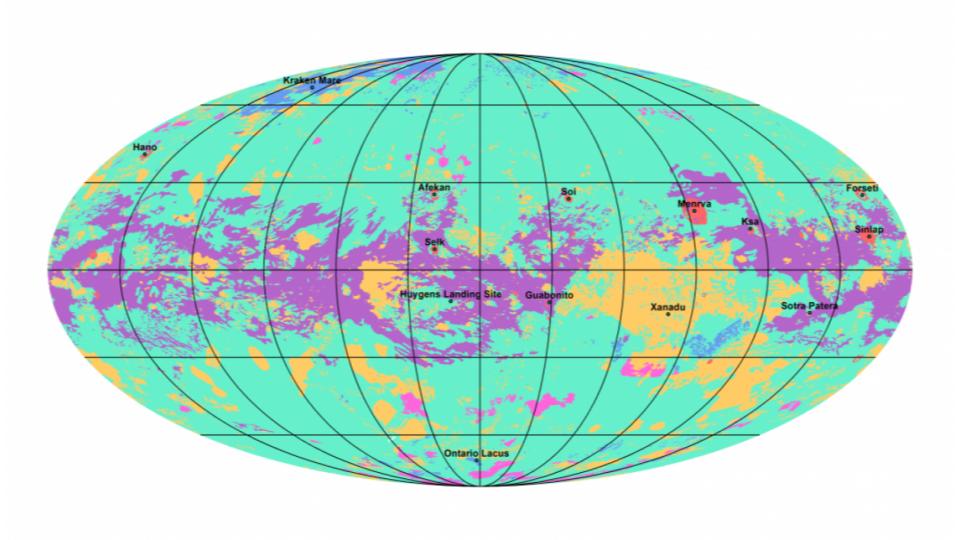

When spacecraft work well, they allow us to do amazing things, and the Cassini space probe was a top-notch example of what is possible.

Launched in 1997, Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004 and would spend just over 13 years exploring the Saturnian system and send back gigabyte after gigabyte of data. All this information will continue to take many more years to process and we are still seeing new information papers published on a regular basis. This week a new global map of Saturn’s moon Titan was published in the Journal Nature. This small cold moon has a thick atmosphere, and a weather system that is driven by methane and ethane, which can be a solid, liquid, or vapor at Titan’s temperature and atmospheric pressure. In studying Titan’s surface, planetary scientists have now mapped out a world with a weather shaped terrain of lakes, dunes, and even river deltas. Like every solid body in the Solar System, Titan does have its share of craters, but they are relatively few in number, indicating that Titan’s surface is generally, like Earth’s, quite young and is likely being renewed as weather erodes away the history of the past. This paper indicates that Titan is likely the most geologically complex system in our Solar System next to Earth.

While Cassini was able to return gigabytes of data over year, more modern missions are returning their data at a much faster rate, and this deluge of data can be overwhelming. This week the Parker Solar Probe dumped all data from its first two orbits of the Sun into online archives where it can be explored by anyone with the will power to figure out how to use the less-than-straightforward data download portals. Now, I’m not going to lie, I tried to find some data that I could share with you, and my 30 minute attempt only gained me a headache and a need to eat chocolate. Luckily other folks have had better luck, and we have images of the solar corona, the Milky Way, and a comet available for viewing on our website.

- Low gravity in space made some astronauts’ blood flow backwards (New Scientist)

Our final story of the day is one that I stumbled across in New Scientist, where I saw a rather disturbing headline indicating that zero-g environments can cause blood flow in some veins to reverse direction. And that sounds like a bad thing, I am here to tell you that this is indeed a bad thing. A new paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association a study led by Karina Marshall-Goebel shows that in a study of 11 astronauts, 6 demonstrated either stack or reversed blood flow in their internal jugular vein, and 1 astronaut developed a blood clot in this vein. If that sounds like a lot, I want to add that this research was inspired in part by two astronauts previously experiencing blood clots in space. While these clots didn’t lead to strokes or other heart or lung complications, it is still troubling, and according to this new paper, “Weightlessness is associated with blood flow stasis in the internal jugular vein, which may in turn lead to thrombosis in otherwise healthy astronauts, a newly discovered risk of spaceflight with potentially serious implications.” It turns out, our vascular system is specifically designed to expect gravity to provide a helping hand, and like so many other parts of the body, our circulation just doesn’t quite work right in space. This is just one more problem that we need to solve if we want to make prolonged stays in space safe. For now, well… researchers will watch and publish what they find.

——————–

That rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are made possible through the generous contributions of people like you. If you would like to learn more, please check us out on patreon.com/cosmoquestx. During the month of November we are running a special fundraiser to support our server costs for 2020. We project costs of $1450 for all of our websites. If you would like to help us reserve our place on the internet, you can donate at streamlabs.com/cosmoquestx. Your donations are tax deductible where allowable in the world.

I will now take your questions, and ask you to please at CosmoQuestX to help me find them in the chat. While you type them in, let me remind you that the Daily Space is a production of the Planetary Science Institute, and is hosted by myself and Annie Wilson.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you c

an help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let you friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.