New planetary science news keeps coming from the European Planetary Sciences Congress, and we bring you highlight about a predictable volcano on Jupiter’s moon Io, Saturn’s moon Enceladus firing snow cannons at, well, everything, and rolling boulders being documented on the comet 67P / Chuyumov-Gerasimenko.

Links

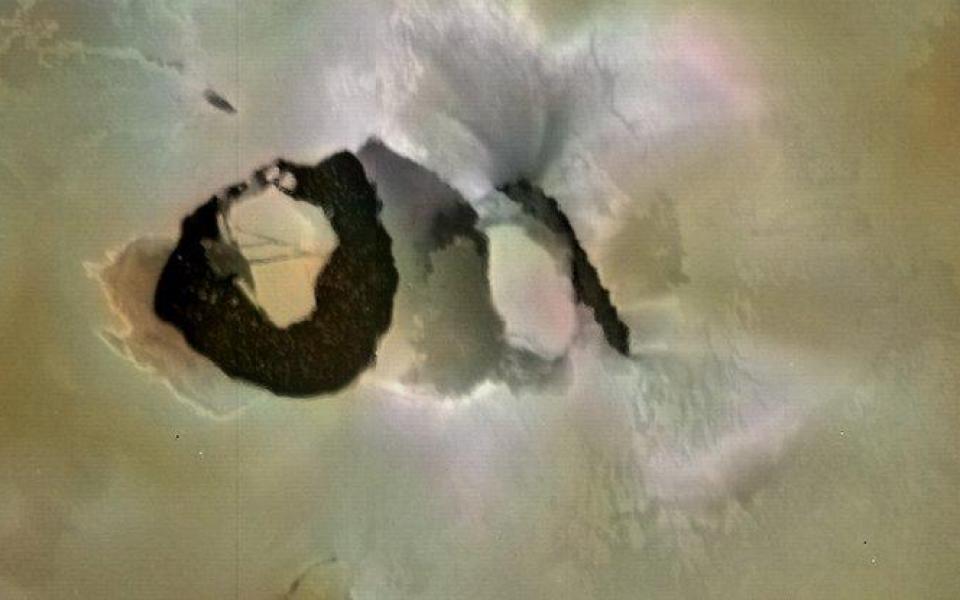

This picture from Voyager 1 shows the volcano Loki on Jupiter’s moon Io. When this picture was taken, the main eruptive activity came from the lower left of the dark linear feature (perhaps a rift) in the center. Below is the “lava lake,” a U-shaped dark area about 200 kilometers across.

https://www.europlanet-society.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Loki.png

Volcano on Io

- Is huge volcano on Jupiter’s moon Io about to erupt this month? (press release)

- Huge Volcano On Jupiter’s Moon Io Erupts On Regular Schedule

(press release) - Io’s Largest Volcano, Loki, Erupts Every 500 Days. Any Day Now, It’ll Erupt Again. (Universe Today)

- Loki Patera (Wikipedia)

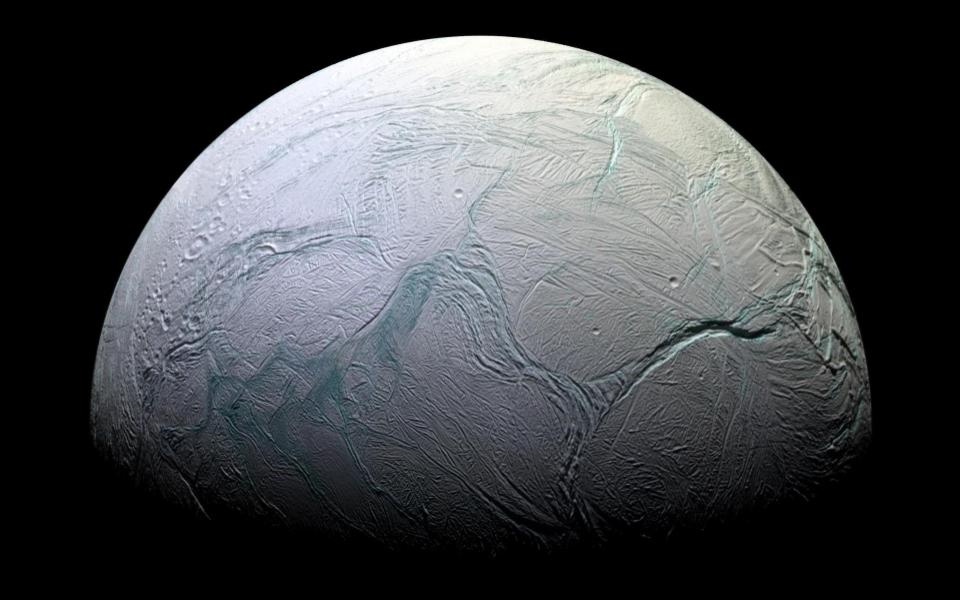

Mosaic of the surface of Enceladus captured by Cassini on 9th October 2008 from an altitude of 25 kilometres. Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Enceladus’ snow cannons

- ‘Snow-cannon’ Enceladus shines up Saturn’s super-reflector moons (press release)

- Saturn’s inner moons: why are they so radar-bright? (EPSC Meeting Presentation)

- Enceladus (Wikipedia)

- Cassini Mission Overview (NASA)

Comet 67P / Chuyumov-Gerasimenko’s rolling boulders

- Comet’s collapsing cliffs and bouncing boulders (press release)

- Rosetta Mission Overview (ESA)

- Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (ESA)

- 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (Wikipedia)

Transcript

As the week rolls on, the news just keep coming from the European Planetary Science Congress in Geneva, Switzerland.

Yesterday, our community erupted with news that something we can’t yet do here on Earth may now be possible on Jupiter’s moon Io. That something? Predicting the eruption of a volcano.

Jupiter’s moon Io was first observed to have active volcanism in 1979 when it was imaged by the Voyager 1 space probe. In the succeeding 40 years, multiple missions and ground based telescopes have worked to observe this small world’s massive eruptions; and when I say massive, I mean massive. The New Horizon’s spaccraft was able to observe Io’s volcano Tvashtar ejecting material 330 km above Io’s surface. If this happened on Earth, the ash would reach within 50 miles of the International Space Station. Io’s largest volcano, Loki, is an incredible 202 km or 126 mi across and contains a massive lava lake. This particular volcano was one of two that Voyager 1 saw erupting, and this is a volcano that scientists have seen continuing to erupt on a regular basis ever since.

Many volcanoes are known to have somewhat regular eruption rates. On Earth, it is common to say “this volcano tends to erupt every 10ish years while that one erupts every 200 years or so.” These kinds of tough estimates are nice, but they don’t exactly tell you when you should look if you want to catch the big event… or avoid the big event.

With Io, things seem to run a bit more on a schedule, however. These eruptions, when viewed from earth, appear as a brightening of Io in the infrared – a color of light that is given off by warm objects, like warm lava. During the 1990s, eruptions were clocked in at a rate of once every 540 days, but overtime, Loki has speed up it’s cycle to an eruption approximately every 475 days.

And guess what – it’s time for one of these eruptions to start.

According to Rathbun, “We think that Loki could be predictable because it is so large. Because of its size, basic physics are likely to dominate when it erupts, so the small complications that affect smaller volcanoes are likely to not affect Loki as much. However, you have to be careful because Loki is named after a trickster god and the volcano has not been known to behave itself. In the early 2000s, once the 540 day pattern was detected, Loki’s behavior changed and did not exhibit periodic behavior again until about 2013.”

If Loki behaves as predicted, it will start it’s eruptions in the next few days to weeks.

This work is the kind that requires a lifetime commitment to a single object, and Julie Rathbun of PSI is the scientist behind both the 2002 publication noting Loki’s original 540 day period, and the work that is predicting this year’s anticipated eruption. This long view allows her to see trends and changes that may not be obvious to others. You can follow along with her research on this object and others, on Rathbun’s Twitter feed @LokiVolcano.

From Volcanic Io, we now take a jump to the left and explore Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The Cassini mission discovered in the early 2000s that this icy moon is surprisingly active, and has numerous geysers capable of spraying water ice. On Tuesday, planetary scientist Alice Le Gall presented new research indicating that these canons of snow may be partly responsible for the shiny white surfaces that are seen not just on Enceladus, but also in the rings, and on the moons Mimas, and Tethys.

Using radar data to measure just how shiny these surfaces are, Le Gall and her collaborators determined a snow cover of at least few tens of centimeters – roughly half a foot or more – is required to explain what they are observing. Consider this, a geysers on Enceladus is responsible for snow fall on moons 50,000 km away. While I would love to send another probe out to explore these moons, I’m really glad Enceladus and its snow canon are far far away.

And yes – I know Enceladus would melt and stop having geysers if it was orbiting Earth instead of Saturn… but snow cannons people. Sometimes you just have to joke about the one time planetary scientists gave something a clever name.

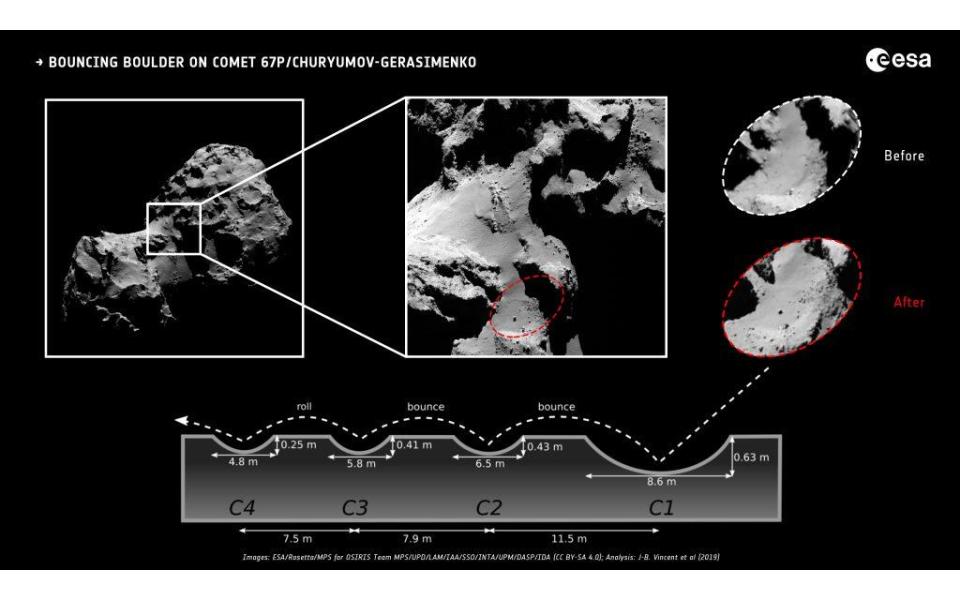

In today’s final story, we turn to another icy object: the comet 67p/Chuyumov-Gerasimenko. Observed by the Rosetta spacecraft between August 2014 and September 2016, this object was imaged from a point far enough from the Sun that it was still dormant all the way through to the comets active, tail forming, solar closest approach. Over these 25 months of observations, numerous changes were seen on the surface of this ice blob, and in a presentation by Jean-Baptiste Vincent that was given the EPSC in Geneva, the Rosetta team has shared images documenting the movement of massive boulders across the comet’s surface, and the collapse of cliff faces.

Using Rosetta’s remarkable imagery, they can actually see not just boulders on the comet’s surface, but also the series of craters and roll marks made as when a 10-m rock fell from cliffs and then bounce like a skipping stone toward its final resting places.

While the moment of the fall was missed, before and after photos allow team members to know this plunge and bounce occurred between May and December 2015, when the comet was most active as it passed near the sun.

During this same period of activity, many other surface changes occurred, including the collapse of cliff faces. In one documented case, a 70-m section of the Aswan cliff was seen to collapse in July 2015, and an outburst of bright materials hinted at an even larger collapse in September 2015 that may have involved 2000 square meters of material collapsing.

These kinds of observations of reminders that comets are transitory objects that are damaged and reduced with their every passage past the sun. Eventually, this comet like many others may completely disintegrate, but for now, it is letting us understand the dynamical processes that create these beautiful objects that are the sources of so many meteor showers.

And that rounds out our episode for today. This has been the Daily Space. We’re new, and we could really use your help getting the word out. If you liked this episode, please subscribe and then encourage your friends to subscribe! We would also really appreciate it if you’d take a minute to leave us a review on iTunes or your favorite podcast directory.

The Daily Space is brought to you by CosmoQuest and is produced by the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non-profit dedicated to exploring our solar system. We are made possible through the generous contributions of people like you. If you would like to learn more, please check us out on patreon.com/cosmoquestx

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.