Our Earth is currently working its way toward being the exact opposite of a snowball Earth as we see glaciers and ice caps receding across the planet. This is fundamentally changing our landscape and how we as humans interact with that landscape.

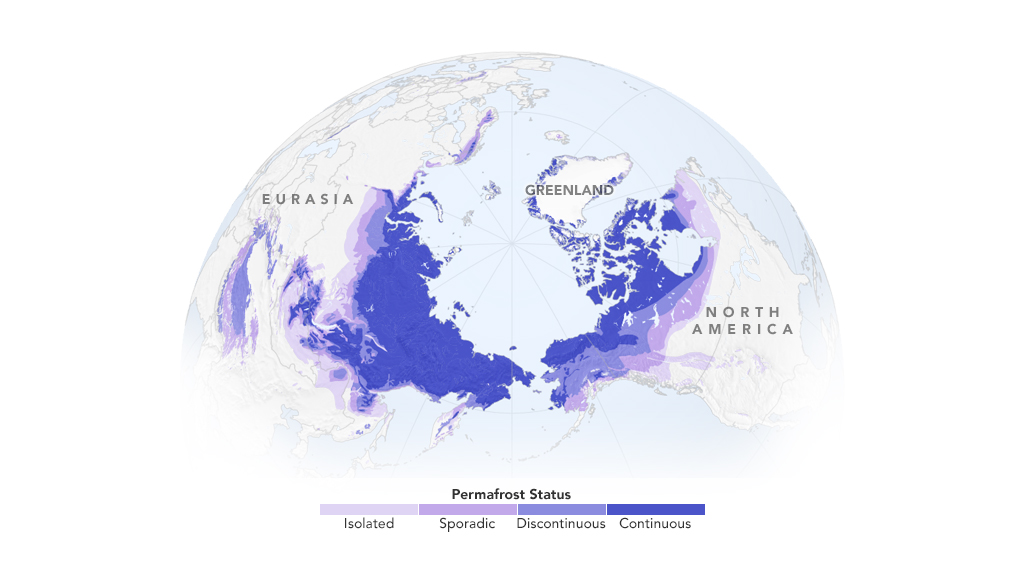

These changes are most evident in the northern, Arctic landscapes of Alaska, Scandinavia, and Siberia where indigenous people’s have lived in close contact with the land, and rely on permafrost for refrigeration and frozen waterways for transit.

As permafrost melts weird stuff is happening. From amazing frozen animals being revealed, to giant sink holes, it’s hard to know what each new day is going to reveal. While we expected the animals, we didn’t expect the sink holes, and we didn’t account for the massive amounts of green house gases being released. Specifically, the potent greenhouse methane is being released.

This work is published in the journal of Global Biogeochemical Cycels and led by G Hugelius.

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

According to team researcher Abhishek Hatterjee, “We know that the permafrost region has captured and stored carbon for tens of thousands of years. But what we are finding now is that climate-driven changes are tipping the balance toward permafrost being a net source of greenhouse gas emissions.”

In the past, permafrost trapped dead plant and animal matter in the ices, locking away their carbon for up to hundreds of thousands of years. As the ice melts, this material decays and releases greenhouse gasses, including the carbon based methane molecule.

Temperatures in the arctic are rising 2 – 4 times faster than global average.

It is possible that we are going to see a feedback cycle where over the next 20 years the release of gasses in arctic regions will drive increasing temperatures. Coupled with the melt of permafrost are other carbon-gas releasing problems like wild fires… because sometimes fire and melting ice like to work together apparently.

Over the next 100 years things should reach an equilibrium again, with the region being roughly balanced between emitting and absorbing greenhouse gasses.

But hey, while the world melts, at least will get more wooly mammoths to study? I for one would be ok with more wooly rhinoceroses and cave lions to see in museums.

Reference