One of JWST’s raison detres is studying the atmospheres of exoplanets – alien worlds orbiting far off stars. In a new paper in Nature Astronomy, we get spectacular evidence that JWST will achieve its goals.

The planet investigated in this study is WASP-43 b, a giant planet – 1.78x the mass of Jupiter – on an orbit 1/25th the distance of Mercury from the Sun, this world is hot. And JWST showed us just how hot.

While we know from orbital mechanics that as the planet goes round and round its star, we are getting to see all sides of the planet at one time or another, we can’t directly make out all those parts of the planet in our images from any telescope – the planet is simply lost in the glare of it’s sun.

In order to study the planet, we have to use a technique called spectroscopy and look at the entire rainbow of light coming from the star and planet together and than tease out what changes systematically with the planet’s orbit – that changing light is from the planet.

Every 10 seconds, for 24 hours, JWST observed WASP-43 and its innermost planet. This allowed them to see a little more than one complete 19.5 hour orbit.

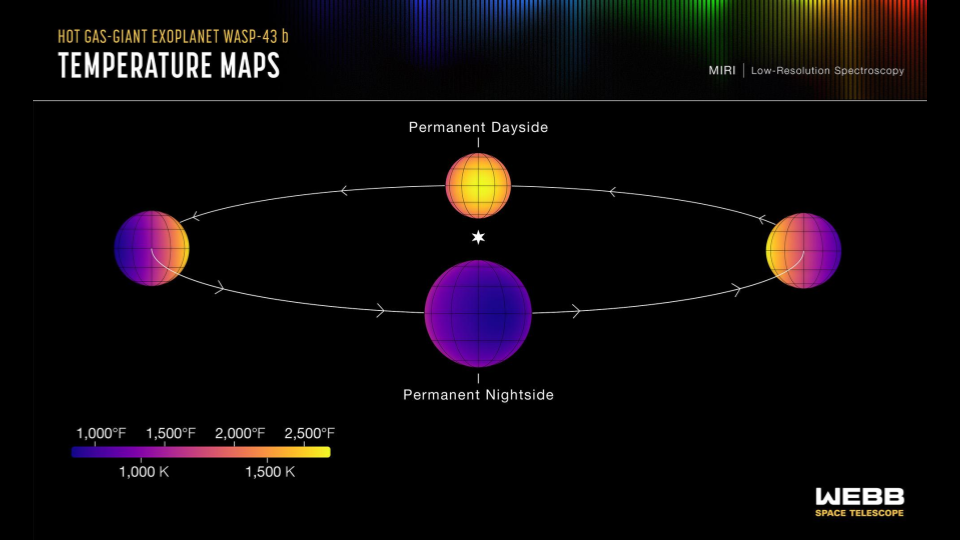

According to lead author Taylor Bell, “By observing over an entire orbit, we were able to calculate the temperature of different sides of the planet as they rotate into view. From that, we could construct a rough map of temperature across the planet.”

They found that WASP 43 b is 1,250 degrees Celsius on the day side and 600 degrees Celsius on the nightside. Through a combination of data modeling, the pieced together that this is a tidally locked work that always keeps the same burnt side facing it’s star, and that an eastward wind distributes the Sun’s heat around to the night side of the world, and shifts the planet’s hottest point to the east of where it is noon on the planet.

Using weather models, they could even figure out that on the world’s nightside there are likely high, thick clouds that act like insulation – a lot like what we see at Venus – and trap the world’s heat in the atmosphere in the worst possible way. JWST even showed evidence of water vapor, which was higher in concentration on the night side than the day side. Oddly, there was no methane present, and according to team member Joanna Barstow, “The fact that we don’t see methane tells us that WASP-43b must have wind speeds reaching something like 5,000 miles per hour. If winds move gas around from the dayside to the nightside and back again fast enough, there isn’t enough time for the expected chemical reactions to produce detectable amounts of methane on the nightside.”

It amazes me how we can understand so much about an alien atmosphere from so little data. With each new world JWST allows us to study, we’ll gain new understanding of just how diverse planets can be. So far, it is clear, our imagination hasn’t been able to anticipate just how creative the universe can get when it comes to planet formation.