Every year, toward the end of January, NASA sets aside a day of remembrance to look back at the three missions that were lost with astronauts aboard:

- Apollo 1 on Jan 27, 1967

- Challenger STS 51L on Jan 28, 1986

- Columbia STS 107 on Feb 1, 2003

I wasn’t born yet when Apollo 1 was lost during a launch test, killing Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. I was raised knowing these men were heroes who lost their lives in a terrible tragedy that led to changes in how space capsules are engineered and how safety is considered during that engineering process.

I was in sixth grade when the Challenger exploded during recess, while all my teachers watched. During my next block – computer science – the principal came on over the intercom to tell us what had happened. The next hour, in algebra, Mrs. Leyland told us about how she knew Christa McAuliffe, they’d been finalists together, and Mrs. Leyland had withdrawn because she wasn’t ready to risk her life, but Christa was. And those seven men and women wanted to explore no matter the cost because, like so many, they were driven to push the boundaries of what is possible. That tragedy led to the founding of the Challenger Centers – science learning centers scattered around the U.S. that help thousands of students learn and dream of seeing themselves in space. That tragedy led to reforms at NASA that I could dedicate an entire episode to, changes that made it clear that concerned engineers must be heard.

I had just finished grad school and was working as a journalist on the news desk at Astronomy Magazine when the Columbia disaster occurred 17 years later. I was driving to the grocery store when a friend in Texas – a friend who’d shared a tent while camping at an astronomy festival with one of those astronauts – called to tell me the crew was gone… scattered over the Texas landscape they called home. These men and women had finished their mission and done their science and were coming home… but the decreasing budgets at NASA combined with a push to launch more missions and accomplish more work had led to tragic failure to maintain high safety standards. Some said it was Challenger all over again… and this time, the lessons learned must not be forgotten…

And now, every year, we remember that these men and women – seventeen lives over 56 years – were individuals who chose to risk their lives, and we can’t waste lives in the name of budgets or timelines. We must remember what has been lost, and we must say this kind of failure is not an option. Never again.

Celebrating the Robots: Ingenuity

The clustering of dates is something I’m sure people more superstitious than me can say a lot about, but I’m here to say that while the winter months are cruel, sometimes these are just coincidences. Even if January brought us the death of a beloved little robot.

On Jan 18, 2024, the Ingenuity helicopter had a hard landing on Mars, and while it was still communicating with its rover, Perseverance, it will never fly again.

Percy is going to be forced to leave its small companion behind as it roves out of radio communications in its future explorations. This four-pound robotic explorer was originally planned to fly a few test missions during the mission’s first thirty Martian days, but its ability to fly and maneuver has allowed it to carry out 72 flights over almost three years.

My favorite moment? Ginny showed us that sometimes when your camera gets out of sync with your clock, you just have to close your digital eyes and trust gravity to show you where the ground is so you can sit down.

Ingenuity – little Ginny – we thank you for your service and what you taught us. I will always be amazed by the landscapes you let us see that were far too dangerous for your many-wheeled brother to try and cross.

You will be missed.

Celebrating the Robots: Spirit and Oppy

Robots on Mars have a long history of exceeding all possible expectations.

The most familiar of these exceptional explorers are Spirit and Opportunity rovers. They landed in January 2004 during a Martian summer.

Slated to explore for only ninety days, Spirit would keep going for six years – until March 22, 2010 – and Opportunity thrived for nearly fifteen years and was declared lost on February 13, 2019.

Ultimately, both these solar-powered rovers were lost to Martian dust. Spirit got stuck in the sand and couldn’t get enough power to stay working. Communications with Oppy were lost during a terrible dust storm.

During their long lives, they taught us that Mars’ surface was once soaked in salty waters, marked with hot springs, and rich in the kinds of clays that could have been a friendly place for life to once have existed. Researchers continue to use these missions’ data to try and understand the history of water on Mars and to help us identify where one day we should go fossil hunting for another world’s ancient life.

Celebrating the Robots: Pathfinder

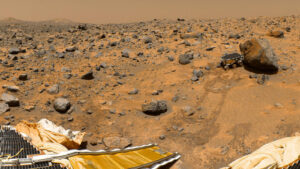

Today’s surface explorers build on the legacy of the aptly named Pathfinder mission. Landing on Mars on the Fourth of July 1997, this lander and its accompanying Sojourner rover were meant to only explore for a week to maybe a month. The batteries in Sojourner just weren’t meant for that many recharges, but this mission managed to last for almost three months. In that time, more than 16,500 images and 8.5 million measurements of the environment were transmitted back to Earth. Among those images was the first evidence of running water on Mars – in the form of the rounded rocks called blueberries – and evidence that lava on Mars solidifies into the same kinds of rocks we have here on Earth.

Celebrating the Robots: The Orbiters

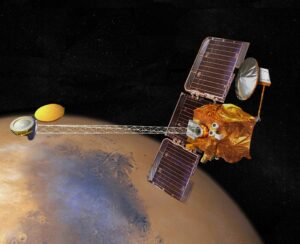

Rovers aren’t the only robots at Mars that live far longer than expected. The eldest active robot is the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft. This orbiting mission was originally planned to do science until mid-2004 and then work as a communications relay until November 2005. Instead, the mission is still doing science, is still acting as a communications relay, and is likely to keep going for at least another year which, let’s be honest, could turn into another decade somehow.

Flying alongside Mars Odyssey is fellow longtimer Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which turned a five-year plan into a nearly 18-year mission that is still going strong.

With them is a growing fleet of missions that just keep going, keep doing science and relaying communications, and keep showing us what great engineering can accomplish.

For robots, we can and we must dare mighty things.

At Mars, our risks and the hard work of so many scientists and engineers are allowing us to explore in ways that will pave the way for future human explorers to follow.

Looking ahead on Mars

The future of exploration is going to be a human-robot alliance. For most exploration, robots are the way to go. They don’t eat very much – just batteries and the occasional bit of nuclear material – and they are much happier being folded up in a tiny dark space for the six-month journey than most people would ever be.

But ultimately, humans want to go to Mars, and where there is a will and a billionaire, there just might be a way.

Computer vision and the ability of AI to recognize features are advancing so fast that I can start to hope that in my lifetime we’ll see rovers autonomously fanning out to look for ancient signs of life on Mars, but part of me hopes that when I’m an old lady, kind of done with the pull of one full gravity, I’ll be able to take my hammer and go do my own fossil hunting in the lower gravity of Mars.

At least a girl can dream.