One of the things that continues to amaze me is how much we still have to learn about solar system formation. Understanding how our universe seeded solar systems in so much variety is work it will take generations to fully understand, but we are making progress, slow and study, in understanding big picture ideas.

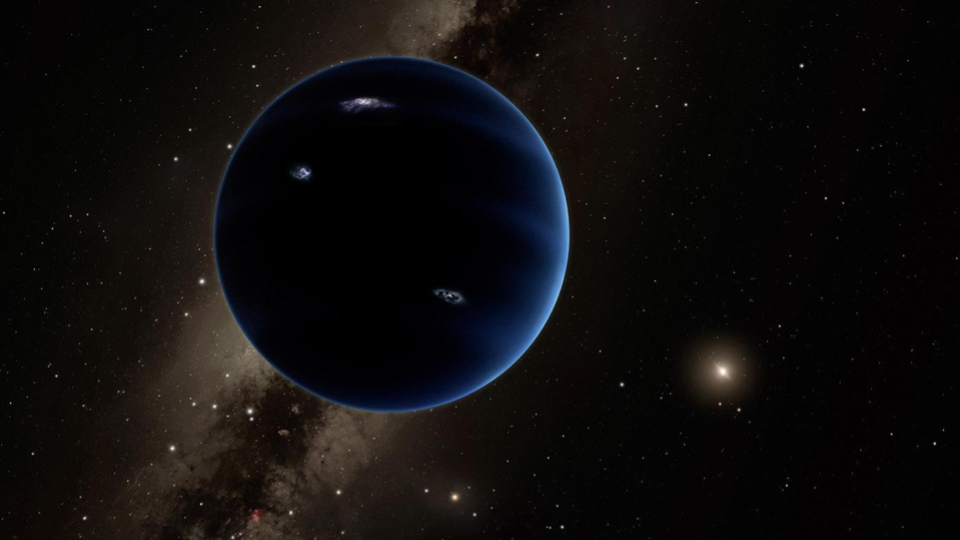

Just how you get planets so far out beyond Pluto had been one of those “But HOW” enigmas, but researchers are finally starting to get a clear picture of what’s going on thanks to computer simulations. A new paper in Nature Astronomy led by André Izidoro looks at how the planet-on-planet gravitational interaction in young solar systems and fling worlds outwards, while the gravitational interactions with surrounding star systems can stop those planets from escaping and stabilize them in far-flung orbits. The paper estimates that 1 in a 1000 solar systems in general could have far-flung planets, and a solar system like ours could have as high as a 40% chance of flinging a 5-10 Earth mass planet into an ultra-wide orbit thanks to various forms of chaos associated with our two ice giants and two gas giants.

Our solar system didn’t form with just the objects we see today. There were once more worlds in our solar system. Some collided, like the young Earth and now consumed world called Thea. Some were probably flung away forever. And some probably just haven’t yet been found.

Here is to hoping the number of planets in our solar system someday goes up as a world or worlds Earth-sized or larger, get confirmed. I’m ready for that kind of a discovery, and Rubin will be just the telescope to make it.