Talk of Mars has been seeping into just about every area of media, as rumors swirl that NASA’s current plans to return humans to the Moon will be replaced with plans to fly directly to Mars. Given that we can’t currently keep people alive on Mars, I’m really hoping that doesn’t happen, and I’d kind of like to walk through life making people read Kelly and Zach Weinersmith’s book “A City on Mars.” Sadly, you can’t actually make people read, but since you’re already hear, I’m just going to say it out loud – sending humans to mars this decade is just a bad idea but the robots we’re sending are doing awesome and I’d encourage every space agency to keep populating Mars with 4 or more wheeled science friends.

Every couple years, our orbit and Mars orbit line up just right to make fuel-efficient flights to Mars possible. The next two windows are in November/December 2026 and December 2028 into January 2029. While NASA doesn’t have anything slated for either launch window, Japan, Indian, the EU, and a commercial collaboration are all gearing up to go, and scientists can look forward to moon exploration with JAXA’s Martian Moons eXploration craft, a new orbiter covered in instruments to look at everything from dust particles to radio waves orbiter, and the much delayed launch of the Rosalind Franklin lander.

And while we wait for our digital collaborators to take flight, their cousins that are already at the red planet are sending us back information that describes a world that was once wetter than previously thought, which means life could have had even better opportunities to evolve than previously thought.

The Book of Mars is written on rocks

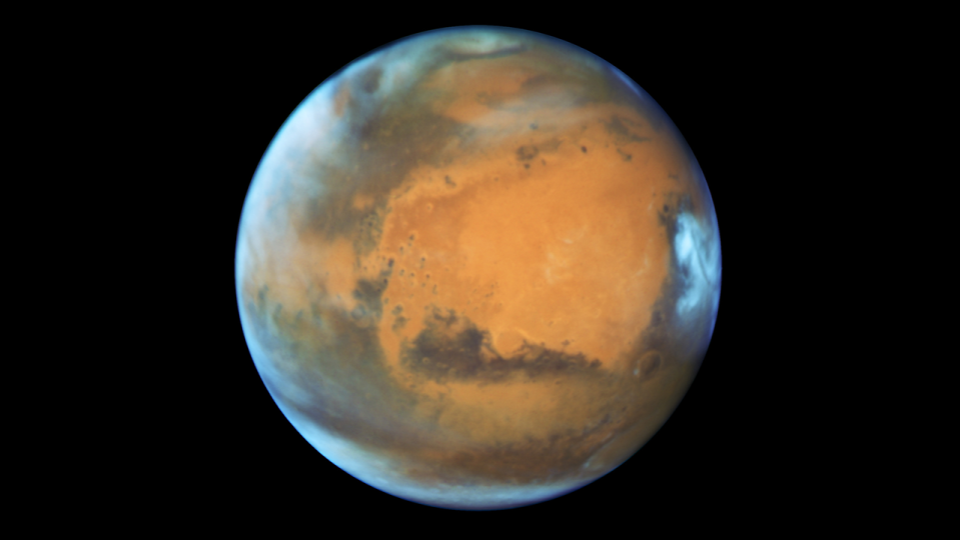

To understand Mars, researchers use every tool at their disposal to understand its surface, including its color. Nicknamed the red planet because it literally appears burnt orange in the sky, Mars is the color of rust, and it has long been recognized that the red came from some sort of iron-rich mineral. Until recently, the mineral hematite had been considered the primary source of this color. Hematite is an iron-oxide mineral (Fe2O3) – which means it contains iron and oxygen. It is known to form in wet conditions but can form without water.

The existence of hematite as small nodules in images from the Opportunity Rover was one of our first clear signs that Mars may once have had liquid water. With the discovery of these pebbles, which were nicknamed blueberries, it was an easy leap to assume that Mars’ red color comes from hematite dust and sand. But you know what they say about assumptions.

This work appears in the journal Nature Communications and is led by Adomas Valantinas.

It sometimes feels like every new piece of data gives us more evidence for Mars having a wet past. In a completely different study, researchers using data from China’s Zhurong rover have uncovered the shoreline of an ancient Martian beach. From May 2021 to 2022, this rover traveled nearly 2 km along what appears to be an ancient shoreline. Along the way, the rover used its onboard ground penetrating radar to map the layers of hidden soils. They were able to figure out that a sloping shoreline, complete with sand, that appears to have been rippled by waves.

Because the ancient beach is essentially sealed beneath subsequent layers of sediments, the shoreline is completely preserved. As researcher Benjain Cardenas puts it, “it’s always a challenge to know how the last 3.5 billion years of erosion on Mars might have altered or completely erased evidence of an ocean. But not with these deposits. This is a very unique dataset.”

These results appear in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences with first author Jianhui Li, and they are consistent with recent work by the Mars Curiosity Lander, which found fossilized ripples in an ancient lake bed, indicating waves stirred an ancient lake in Gale crater.

While ancient Mars may have been warm and wet, modern Mars is a desert wasteland. That doesn’t mean the water is gone, however. It just means it’s gone from Mars’ surface.

Researchers believe that a lot of Mars water has seeped into the world’s regolith… which is a fancy word for soil. According to a new paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research Planets, Mars regolith varies greatly from place to place, and these variations mean some areas of Mars are better able to absorb and retain water than others. According to the Tohoku University press release on this research, “Like a sponge, highly absorptive regolith in Mars’s mid- and low latitudes retains substantial amounts of absorbed water. Some of this water, the findings showed, remains on the surface of the regolith as stable adsorbed water.”

Team member Takeshi Kuroda further explains, “The model can be used to study how water on Mars has changed, and how it may have moved deeper underground near the planet’s mantle.”

Essentially, when we can one day dig into Mars surface, we should find ice-rich soil within meters of the surface with even deeper reservoirs locking away water that once flowed as lakes and small oceans, but just like on Earth, how much moisture we find will vary from place to place.

Impacting space rock triggers quake

While a lot of time is spent studying Mars’ ancient climate, some instruments are focused narrowly on Mars current conditions. One of those instruments was Mars Insight Lander’s seismograph. Designed to do one thing – measure Earthquakes on the red planet – this extremely sensitive instrument found signs that Mars just might still have some geologic activity. Before researchers can say that for certain, however, all other possible sources of ground shaking need to be eliminated – including the shaking associated with falling space rocks.

And, we now know, at least one quake was actually a falling space rock.

In a pair of papers in Geophysical Research Letters, researchers led by VT Bickel and Constantinos Charalambous were able to identify 123 new impact craters that occurred near InSight lander potentially while it was operating, and they link 49 seismic events to including the formation of a 21.5 meter crater near Cerberus Fossae.

It had previously been thought that small impacts would vibrate through Mars’s surface but not create the mantle-penetrating seismic waves. The formation of this new crater, however, seems to indicate that meteoroids can quake Mars mantle. This crater is linked to the high-frequency seismic event S0794a, which occurred in February 2021.

As Charalambous puts it, “We used to think the energy detected from the vast majority of seismic events was stuck traveling within the Martian crust. This finding shows a deeper, faster path — call it a seismic highway — through the mantle, allowing quakes to reach more distant regions of the planet.”

Previously, Cerberus Fossae had been identified as a seismically active region because so many quakes were occurring there. This research raises the question, was this impact crater a one-off event, or is there something about the geology that causes impacts there to show up in Insight’s data.

Clearly, more Martian seismography is needed. When that will happen, I can’t tell you.

Also, this tells us Mars gets fairly significant craters on the regular. Rocks that our atmosphere would burn up to safe sizes are able to easily make it to Mars surface and make their marks. This research found the impact rate was 1.6-2.5 times higher than previously thought, with 100s of impacts greater than 3.9 m occurring every year. If humanity ever finds itself spreading across the red planet, asteroid impacts are going to be far more of a concern than I imagined, with at least 1 impact a year per Texas-sized area of Mars.

So, more robots on Mars, more seismographs on Mars, and maybe keep the humans on Earth where our sky falls a whole lot less.