One of our greatest frustrations as a science, is we astronomical and planetary scientists can’t do the same kind of experiments that other kinds of scientists get to do. We look at things from millions of miles to billions of light years away and try and understand their inner workings while only being able to see their surface.

While astronomers really can’t do anything to improve our situation, our planetary science siblings do get periodic opportunities to fling spacecraft around distant worlds and use gravity to probe the internal workings of distant worlds.

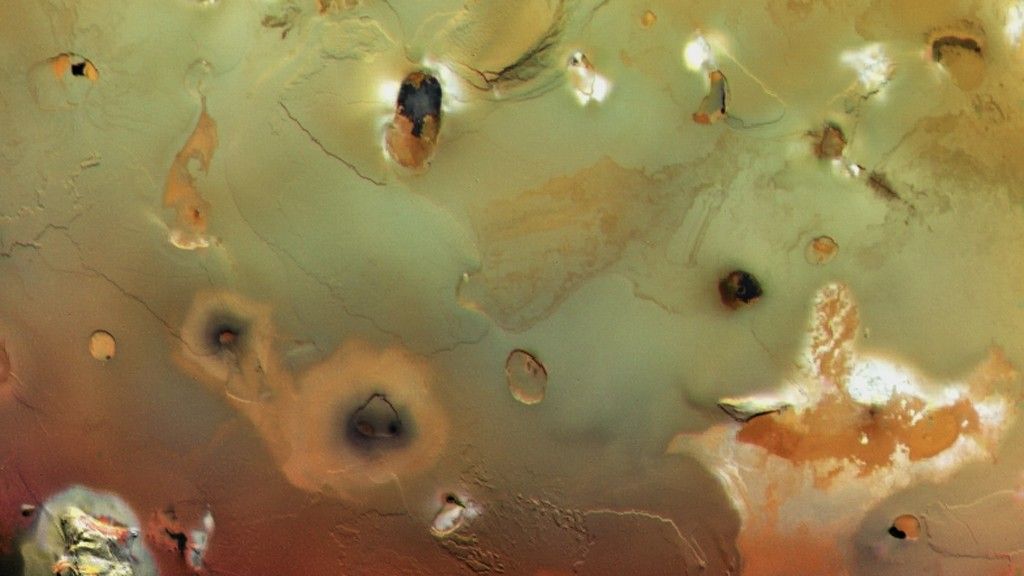

Most recently, the Juno mission at Jupiter has made a series of flybys of the volcanic Moon Io. By looking at how Io’s gravitational field altered the mission’s motions, researchers have been able to very roughly measure Io’s internal structure, and it turns out this hellscape of volcanism isn’t as gooey in the center as we thought. Since the Voyager 1 probe first saw volcanic eruptions in March 1979, researchers had theorized that the constant squish and release the world experiences as it gets closer and farther from Jupiter was building up sufficient heat to maybe give Io a molten core or at least a shallow global magma ocean. The data, however, point to Io actually having magma chambers that feed the various volcanoes.

According to study lead author Ryan Park, “Juno’s discovery that tidal forces do not always create global magma oceans does more than prompt us to rethink what we know about Io’s interior. It has implications for our understanding of other moons, such as Enceladus and Europa, and even exoplanets and super-Earths. Our new findings provide an opportunity to rethink what we know about planetary formation and evolution.”