Humans like to label things. In general, this works out for us. If you go to a furniture store and ask for a sofa, they will show you things multiple people can sit on that are clearly sofas. Ask for a chair, and they will show you seating for one in a variety of styles. The problem is, there are things out there, like my Ikea hack of not-a-chair-or-sofa that defies classification.

In our solar system, we don’t … or at least we don’t yet… have solitary orbiting sofas and chairs. What we do have are comets and asteroids.

Asteroids, like the amazingly well-imaged Ceres, Vesta, Bennu, and Ryugu, are primarily made of rock. Their orbits are boring, with everything being explainable with gravity and the Yarkovsky effect, which just says that a hot surface can radiate enough energy to slowly change an asteroid’s orbit.

Comets, like the dramatic 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, are largely ice, and when something causes those ices to go from solid to gas, the expanding gases can act like small thrusters. This was dramatically imaged by the Rosetta mission. These naturally occurring jets add a bit of chaos to the orbits of comets that make accurate predictions of their orbits over long periods of time just not possible.

And then there are the objects that look like asteroids and move like comets.

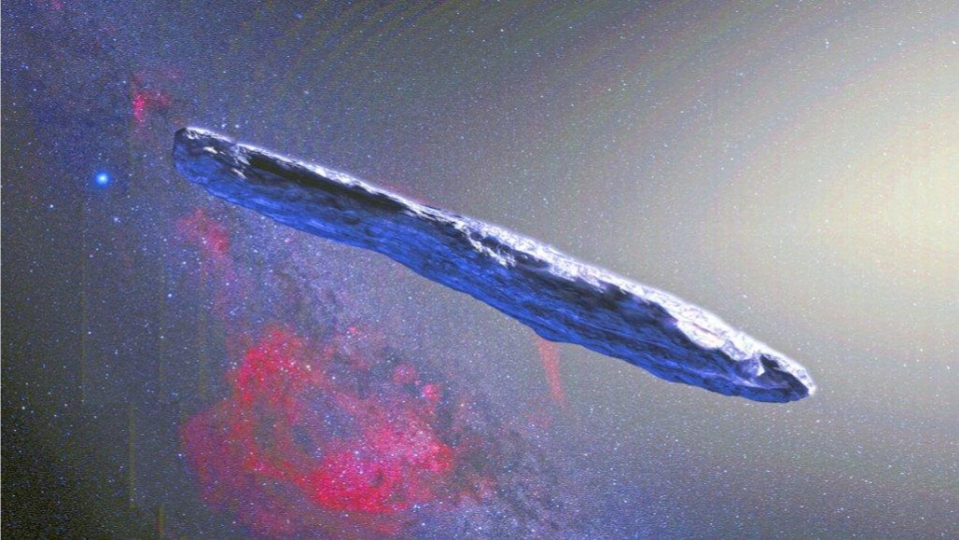

Called dark comets, because they aren’t shiny like their more obviously icy brethren, we only know these objects’ true identity because their orbits can’t be explained using orbital mechanics with a dash of Yarkovsky effect. Instead, these dark comets have the slightly erratic motions typical of comets. The alien comet Oumuamua is an example of this kind of object. Discovered in 2017, it passed through our solar system on an orbit that had some folks screaming it was aliens, while calmer heads said “Nah, it’s just a comet crusted over with dark stuff, like a blackened snowbank at the end of winter.” Oumuamua made researchers wonder if other dark comets might be lurking in our solar system.

In a new paper in Publications of the National Academy of Science, researchers discuss 7 dark comets that orbit the Sun in two distinct families.

The larger ones – with sizes hundreds of meters or many football fields across – have orbits that go from out near the Sun and plunge in through the inner solar system. The smaller ones are just tens of meters across and have orbits that keep them close in, where they orbit among the terrestrial planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

At this point, we don’t know if these objects are somehow related, where they originated from, or even if their anomalous orbits are truly because they have comet-like jets. That hypothesis is just one that fits their motions.

What we do know is we’ve found a new cool mystery to chase, and in the ill-conceived tradition of astronomy, we’ve named them dark comets, even though they may not actually be comets.