In Roman mythology, Jupiter is not exactly a faithful god. Some would allege him willing to bed just about anything, and this tendency shows up in some really funny ways in how we name things. Jupiter’s four largest moons, for instance, are named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto after two mortal women, a beautiful prince, and a nymph, all of whom Jupiter had dalliances with. Basically, since the time of Galileo 400 years ago, the planet Jupiter has been condemned to be chased round and round by four of his lovers.

And then, in an act that continues to amuse me, NASA launched a mission called Juno – named after the Roman goddess who was Jupiter’s wife! – and they sent Juno to explore Jupiter’s moons. This means, for the past several years, as part of Juno’s extended mission, the namesake of Jupiter’s wife has been sidling up to the moons named after his lovers, exploring them with her cameras and then continuing on. While unable to visit all the Galilean moons, Juno has made a series of passes by Ganymede, Europa, and most recently Io.

In February, Juno was within 930 miles of Io’s surface. Since then, Juno’s orbit has been shrinking, bringing the mission in closer to Jupiter and away from those circling moons.

Put simply, Io and Juno have parted ways, and Juno is now snuggling down into tighter orbits around her Jupiter.

In the months since that final closest approach, researchers – professional and volunteer citizen scientists – have been pouring over images and other data from Juno to learn all they can about this amazingly volcanic world. In this segment, we’re going to take you on a quick tour through our favorite new discoveries.

Io in Review

Thanks to the amazing imagery from Voyager 1, we’ve known since 1979 that Io has active volcanism. As telescopes on Earth have gotten bigger, we’ve struggled to make out hot spots and other telltale signs of eruptions from our location at least 365 million miles away. While this has been enough to keep track of some features, it just isn’t as satisfying as getting an up-close look.

Enter Juno. Launched in 2011, this little mission arrived at Jupiter in 2016 on what was intended to be a roughly three-year science plan. Its amazing success, however, earned Juno a mission extension. During this bonus round of science, the mission team has been maneuvering Juno on ever-shrinking orbits that have allowed it to spend about a year flying past each of the three inner Galilean moons, making 2023 and heading into 2024 the year of Io.

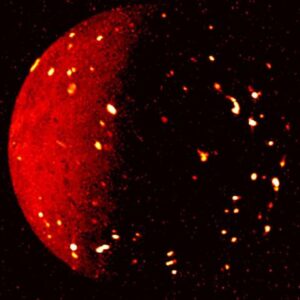

In the lead-up to this year of encounters, Juno brought us an infrared image that reminds us just how many active volcanoes coat this world. Taken from 50,000 miles away, this image makes it clear Io is a place of lava and brimstone; the kind of world where Darth Vadar might feel right at home.

The flybys started in earnest in December 2022 and teased us with what was yet to come. In this first encounter, we got a sense of the geological and mineralogic diversity of Io’s surface.

Things weren’t much better when we saw Io in May 2023, but at least we were getting a different perspective with every pass, allowing us to see more and more of Io’s surface

It was the July 2023 flyby, which brought Juno within 13,700 miles, that brought us the science many of us were watching for. In these images, volcanoes previously observed by Galileo in 1996 and New Horizons in 2007 were seen one more time. According to team researcher Jason Perry, “When I compared it to visible-light images taken of the same area during Galileo and New Horizons flybys (in 1999 and 2007), I was excited to see changes at Volund, where the lava flow field had expanded to the west and another volcano just north of Volund had fresh lava flows surrounding it. Io is known for its extreme volcanic activity, but after 16 years, it is so nice to see these changes up close again.”

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS, Image processing by Ted Stryk

Io’s active volcanism was highlighted again in October 2023 when images of a quarter-phased Io contained a bright eruption shining from the night side of the world. Juno had caught Prometheus volcano ejecting a plume of material.

With each flyby, we saw more. The December 30 and February 3 flybys brought Juno within 930 miles of Io’s surface. Illuminated by the Sun on one side, with light reflected off Jupiter on the other, this view gave us a full disk image that revealed mountains, and even a lava lake with mountains rising from its surface.

A couple of months later, the mission team had a chance to dig into the data and pull out the details.

While lots of folks are going over the active volcanoes caught erupting, the detail that has my attention is Steeple Mountain, a razor blade of a mountain that is 3 – 4.3 miles in height. For comparison, Mt. Everest is 5.5 miles high.

Also defying expectations, one of Io’s most famous volcanos, Loki Patera, is now associated with a roughly 130-mile-long lava lake that contains, according to principal investigator Scott Bolton, “…crazy islands embedded in the middle of a potential magma lake rimmed with hot lava. The specular reflection our instruments recorded of the lake suggests parts of Io’s surface are as smooth as glass, reminiscent of volcanically created obsidian glass on Earth.”

To be honest, this is just was what obvious in the images, and it isn’t even all that was standing out demanding researchers’ attention. It will take months and even years to get all possible science out of this data.

And when those results come out, we will bring them to you right here on Escape Velocity Space News.