Annie catches us up with an update from SpaceX, a surprise rocket launch with a space jellyfish, and news of the latest spacewalk

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space for today November 20, 2019. I am your host Annie Wilson. Most Mondays through Fridays, our team will be here bringing you a quick rundown of all that is new in space and astronomy.

Usually Wednesdays are for Rocket Roundup, and today is no different.

But before we get to the surprise launch, an update from SpaceX:

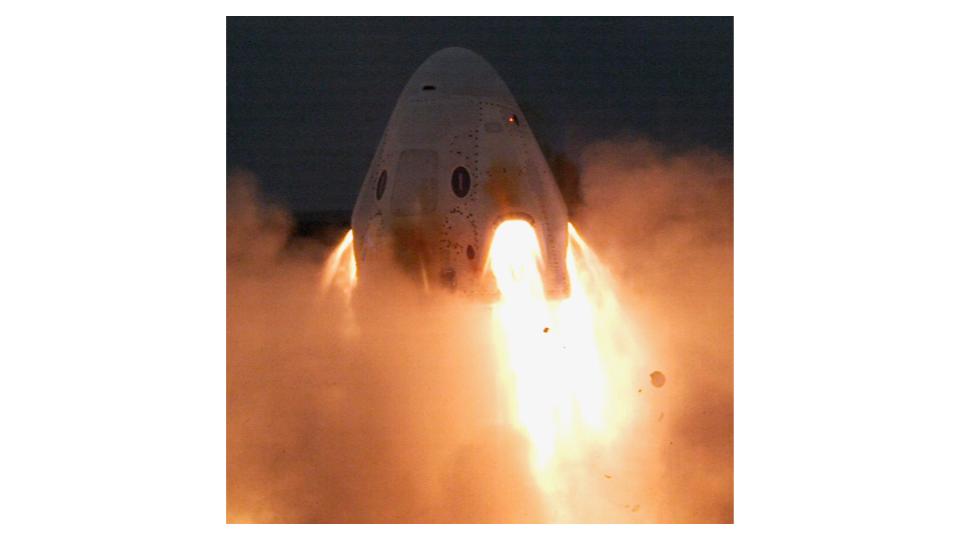

On 13NOV19, SpaceX successfully conducted a “hold-down” static fire test of its Crew Dragon capsule. And yes, it’s exactly what it sounds like: the rocket is held down so it doesn’t take off while the engines are fired.

- SpaceX’s Crew Dragon Abort System Aces Ground Test Ahead of Major Launch (Space.com)

- SpaceX Completes Crew Dragon Static Fire Tests (NASA)

- Elon Musk: SpaceX to Launch Vital Crew Dragon Escape System Test Soon (Space.com)

- SpaceX Confirms Dragon Capsule Was Destroyed in Test ‘Anomaly’, Could Affect Crew Launches (Space.com)

At 3:08 pm EST / 20:08 UTC an updated Crew Dragon capsule performed a successful static fire test of its 8 Draco thrusters, simulating their operation during a pad abort emergency. The failure of a check valve during a similar test almost 7 months ago resulted in the destruction of another Crew Dragon capsule. That test was done on a capsule which had made a successful automated flight to the ISS which delivered literal tons of cargo and scientific experiments before safely returning to Earth.

That particular failure was traced back to a modern design of check valve that keeps liquids inside things such as fuel lines separated until a certain pressure level is exceeded, preventing the mixing and flow of those materials until precisely the desired circumstances or conditions are met. Check valves are meant to be reusable, which would have allowed for faster turnaround time when refurbishing a craft for future flights. Unfortunately, such valves have also have been proven notoriously unreliable, the failure this past April being just one of many found during testing of this and other rocketry designs.

That failure triggered a design change where the new capsule now incorporates more reliable burst discs rather than check valves. Rather than opening at a designed pressure level, burst discs simply fail, “bursting” to allow the desired flow, and obviously once they’ve been used, they must be replaced in order for the capsule to be reused. This increases the amount of work to be done for refurbishing, but also increases the safety for the crew aboard.

If not used during an abort event or test, such discs can be checked for integrity w/out being replaced, so they will not necessarily need to be replaced following every single mission.

Both NASA & SpaceX have released statements to the media and on Twitter indicating the test was entirely successful. This clears the way for a final uncrewed in-flight abort test flight sometime in the next 1 – 2 months, where the craft will simulate an emergency requiring the capsule to get the crew to safety shortly after launch. It will be the highest stress test of the launch abort system, and a passing result is needed before Crew Dragon can be certified for flights with crews aboard.

Now, for that surprise rocket launch! If you tuned in last week, you may recall that an Expace Kuaizhou 1A rocket launched. Well, just four days later on November 17 at 9:52 AM UTC, Expace launched *another* Kuaizhou 1A. This is thought to be the shortest break between two consecutive launches of the same model of rocket in China.

- KL-Alpha A, KL-Alpha B (RocketLaunch.Live)

- KL-Alpha A, B (Gunter’s Space Page)

- “One Arrow Double Star” launched successfully the first international project delivery of Microsatellite Research Institute (Translated from Chinese at Yicai.com)

- The KL-α satellite undertaken by the Satellite Innovation Institute was successfully launched at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center.

The launch patch for this mission is a diamond shape, with the rocket going right up the middle. A red-orange circle against a light blue background appears to be rising from the exhaust plume surrounding the Transporter-Erector-Launcher. Two satellites are pictured, which corresponds with the payload of KL-Alpha A and KL-Alpha B. Five stars can be seen, one for each launch of this rocket model.

On the left edge of the patch, Kuài Zhōu Chǔ tiān is written in Chinese characters while the right edge bears the name of the mission: “KL-Alpha”.

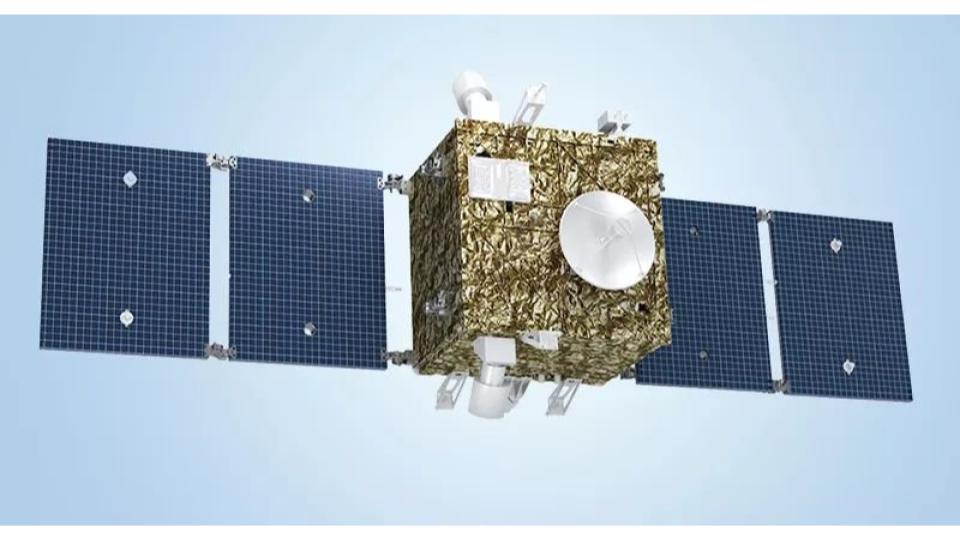

Now, let’s chat about the payload for a second. Not only was it launched in China, it was built in China. KLEO Connect, a German company, put out a request for bids in 2017 for two satellites. The Institute of Microsatellite Innovation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences successfully won the bid.

The two satellites, KL-Alpha A and KL-Alpha B, are essentially technology demonstrations for KLEO, a German “New Space” start-up company. Both satellites are capable of utilizing the Ka band, but are different masses and will be put into two separate orbits. One satellite will be at 1050 km altitude and the other will be at 1425 km altitude.

KLEO Connect’s long-term goal is to place a constellation of 300 satellites in Low Earth Orbit for the purpose of supporting the emerging “Industrial Internet of Things” market. This technology could be used to communicate with and track ships, mining operations, farm equipment, and long-haul trucks — just to name a few applications.

Photographer “Heaven and the Sky” captured this image of the rocket’s luminous exhaust trail in northern China. There’s actually a name for this phenomenon: space jellyfish.

This happens because of two things:

- The Earth is round.

- The timing of the launch.

If this was a night launch instead of an evening launch, it would be too dark to see the exhaust plume. Around twilight, the sun is out of sight of the viewer (making it dark), but is still lighting up part of the sky. Here, the plume is condensing — becoming liquid droplets or ice crystals — in the air and that is lit up by the sun.

Our final story covers a mission taking place currently aboard the ISS, the roots of which go back decades: we’re going to talk about the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, the single biggest, heaviest and most expensive scientific instrument aboard the International Space Station.

- Veteran Spacewalkers Begin Complex Work to Repair Cosmic Particle Detector (NASA)

- Astronauts complete bonus objectives in first in series of AMS repair spacewalks (Spaceflight Now)

- Spacewalkers Complete First Excursion to Repair Cosmic Particle Detector (NASA)

- 50 years after Alan Bean launched on Apollo 12, Cygnus supply module named Alan Bean heads to ISS (Orlando Sentinel)

- S.S. Alan Bean NG-12 Cargo Delivery Mission to the International Space Station (Northrop Grumman)

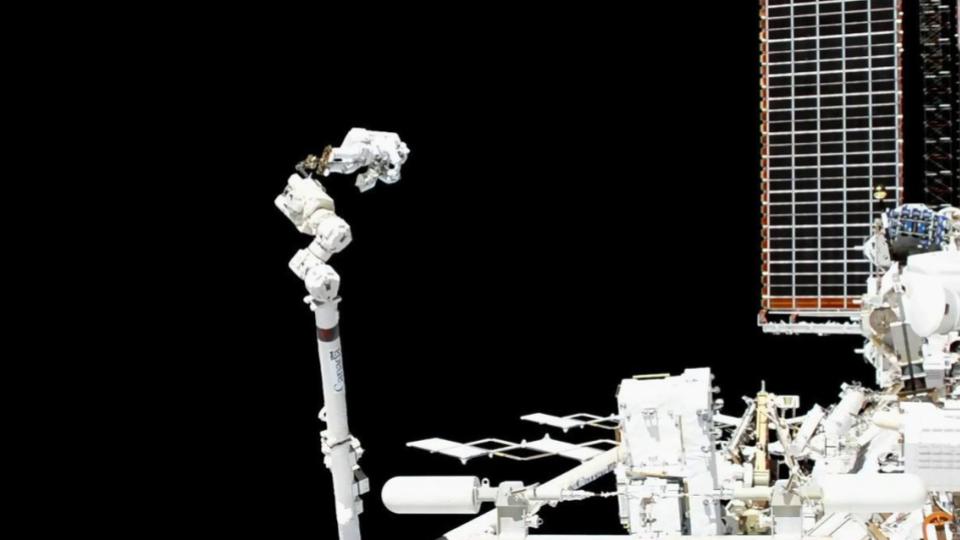

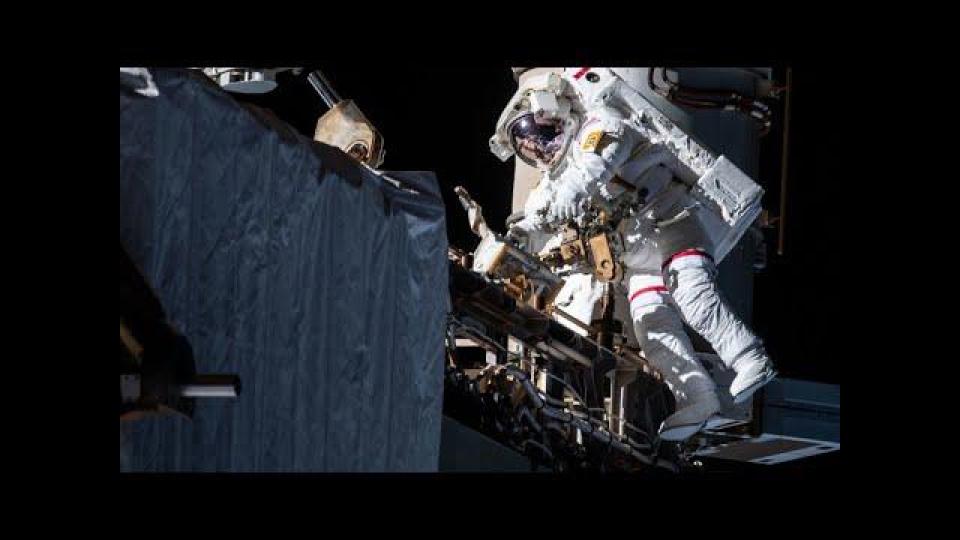

This past Friday, ESA astronaut and current ISS commander Luca Parmitano, and NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan spent just over 6 and a half hours performing a spacewalk to service the AMS which is an extremely sensitive cosmic ray detector. As can be seen in the image, they were supported in this effort by the Canadarm, which was operated by NASA’s Jessica Meir.

CREDIT: NASA (via YouTube.com) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evaBhht5uGA

Due to the complexity of the device and the complicated, painstaking nature of its development, the AMS was never intended to be serviced in orbit. The device came board the ISS on STS-134 in May of 2011, and Shuttle flights ended shortly thereafter, ending practical methods of returning the device to Earth for servicing, if needed. So when the four cooling pumps vital to its operation began to fail a few years into its mission, it was thought that it would only be a matter of time before the detector would no longer be able to perform its ground-breaking work.

Weighing in at over 6,800 kg / 15,000 lbs, the already massive device was not designed with the handrails, attachment points, or extra internal clearances needed for space walkers in bulky EVA gear to perform servicing work, and it took a team of engineers and astronauts over 4 years to develop procedures that might allow the work necessary to be accomplished. In the process, they developed some two dozen new specially designed tools for the tasks which need to be completed to service the system’s all-but failed liquid CO2 cooling system.

Further complicating matters, the internal structure contains many sharp edges and delicate components which can simultaneously provide hazards to astronauts and the instrument alike. Parmitano and Morgan trained extensively on the techniques and procedures, performing no less than seven full-duration sessions of ground-based simulation prior to heading to the ISS this past July.

According to Tara Jochim, the AMS repair manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, “We had to go off and figure out how to create a work site, we had to build new handrails to install on existing hardware, we had to deal with existing sharp edges and in a lot of cases, we’re creating new sharp edges using tools that have sharp edges on them. We did as much as we could to minimize that risk to the crew member and then, of course, to the [repair] of the payload itself, but they are certainly very challenging and technically difficult EVAs.”

Despite these obstacles, Parmitano and Morgan were able to not only complete all of their assigned tasks, they were also able to accomplish several “get ahead” tasks which will reduce the workload for upcoming EVA’s, the next of which is scheduled for early Friday morning and will be broadcast live on NASA TV. Two other EVAs are tentatively planned, but will be scheduled based on flight and ground engineers’ assessment of the work completed during the 1st two. If the 2nd EVA on next Friday goes as well as the 1st one did, those two missions may be shortened, or perhaps even combined into a single EVA.

While this spacewalk was intended to “prepare the work site” by opening the device and pre-positioning the tools and other gear needed for the upcoming work, the actual repair work will begin the day after tomorrow. The astronauts will need to, among other things, cut and splice 8 separate cooling lines & splice in the new lines which will lead to a brand new cooling unit.

For those keeping track, last Friday’s EVA was the 222nd spacewalk in the history of the ISS. It was Andrew Morgan’s fourth and Luca Parmitano’s third career EVA overall.

And now, for some bonus facts.

BONUS FACT #1: In a tradition dating to the early days of NASA spaceflight, EVAs are always performed with a trained astronaut on the ground acting as a liason between the space walkers and mission control teams, leadership & engineers.

BONUS FACT #2: For Parmitano, this was his 1st EVA since his suit malfunctioned in July 2013. His helmet gradually filled with water and required an emergency return to the ISS before he literally drowned in his spacesuit. Since then, EVA suit upgrades and procedures — including the addition of an absorption pad inside the helmet — have prevented any more of THOSE problems to this point.

Finally, there will be many launches over the next two weeks. Here is a list – we will stream some of these if schedules permit!

That rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond.

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you can help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let you friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.