Today is our Weekly Rocket Roundup. The “CSS Alan Bean” Cygnus launched aboard an Antares, the ISS got a cookie oven, Boeing’s Starliner successfully abort-tested, and China sent up 2 rockets, all this week.

Hello, and welcome to the Daily Space for today November 6, 2019. I am your host Annie Wilson. Most Mondays through Fridays, either I or my co-host Dr Pamela Gay will be here bringing you a quick rundown of all that is new in space and astronomy.

First up: On November 2nd at 1:59 PM (UTC), Northrop Grumman launched Cygnus mission NG-12 aboard an Antares rocket.

- CRS2 NG-12 (Cygnus) (Rocket Launch Live)

- Launch video (YouTube)

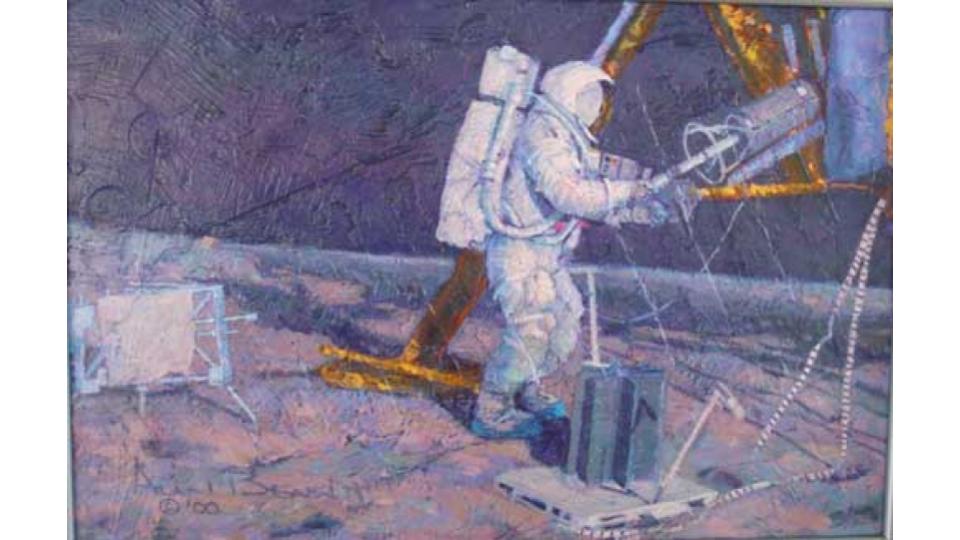

Orbital ATK, the makers of the Cygnus spacecraft & a subsidiary of Northrop-Grumman, have a tradition of naming their spacecraft, and the NG-12 mission was no exception. The Cygnus spacecraft for this mission was dubbed the “CSS-Alan Bean” in honor of the recently deceased American astronaut (March 15, 1932 – May 26, 2018) who aside from being a decorated naval aviator, an aeronautical engineer, the fourth human to walk on the Moon, commander of the Skylab 3 mission, and inductee of several halls of fame & honor societies, was also a prolific artist.

CREDIT: Alan Bean / The International Museum of Art, El Paso, TX

Bean resigned from NASA in 1981 to focus on his art, which often included surprising colors, the addition of which he said was deliberate: “I had to figure out a way to add color to the Moon without ruining it,” further stating that “If I were a scientist painting the moon, I would paint it gray. I’m an artist, so I can add colors to the moon.” His work also included textured medium produced by including bits of actual moon dust, pieces of his personal Apollo mission patches (which had been heavily soiled w/lunar dust, providing him a ready source of that material), and by application of various implements such as the very hammer he used to pound the flagpole into the lunar surface and a bronzed moon boot.

Bean remarked that he felt personally driven to produce his art, and to share it piece by piece with humanity since no other artist from any era had the first-hand experience he did. He commented that “I’m the only one who can paint the moon, because I’m the only one who knows whether that’s right or not.”

Prior to his death, Bean was the last surviving Apollo 12 astronaut.

Included in the cargo aboard the “Alan Bean” is the first dedicated for-food oven designed for use in microgravity. Made by a company called Nanoracks in partnership w/DoubleTree hotels, astronauts & scientists alike are interested in seeing just how the oven will perform when paired with DoubleTree’s signature cookie dough in upcoming experiments. The dough has been waiting in a freezer aboard the ISS since the CRS-18 mission arrived this past summer.

CREDIT: DoubleTree by Hilton

- Astronauts getting ready to bake choc-chip cookies (Kidsnews.au)

- The Zero G Kitchen Space Oven (Official site)

- Astronauts on the ISS can bake cookies in space for the first time (Slashgear)

- Houston, we have a cookie (Hilton Doubletree)

The “Zero G Kitchen Space Oven” doesn’t depend on the force of gravity which stimulates the convection that is so vital to cooking with an oven on Earth. Instead, it will use several evenly distributed heating elements which will work together like a toaster to produce evenly radiated heat. This in turn requires that whatever is to be cooked must be held in place somehow, and the Texas-based NanoRacks designed a specialized silicone pouch for this task. Each of these pouches are clear to allow visibility of the contents, have a pair of 40 micron filters to allow hot gasses & steam (& hopefully that fresh cookie scent!) to escape while keeping any possible crumbs from escaping. The module is installed in the KIBO module of the ISS, and is equipped w/sample trays & cooling racks to finish out the process

As this oven is only a testbed designed to show the feasibility of such activities in space, and to allow scientists to observe the results of its operation, the scale is small: only one cookie will bake at a time at a temperature of ~350 F / 176.7 C , and there are only five cookies in the ISS’ freezer.

There is more bad news: the initial “results” will not be eaten, as they are due to be sent back to Earth for analysis by scientists. These samples will help them determine the physics & chemistry unique to cooking in the microgravity environment which will hopefully allow larger, more versatile ovens to be designed & used in the future… and answer once and for all the age-old question of how/whether baked cookies rise in microgravity, and what they look like if they do!

Next up: China had a busy couple of days with not one, but two launches!

Credit: Xinhua

- China launches new Earth observation satellite (Xinhuanet)

- Sudan Has Launched Its First Satellite; A Remote Sensing Satellite (Space in Africa)

- Inside Sudan’s National Space Programme (Space in Africa)

- China launches Sudan’s first ever satellite: official (Phys.org)

- Chinese mapping satellite launches on Long March 4B rocket (Spaceflight Now)

- Gaofen 7 (RocketLaunch.Live)

- Gaofen 7 (GF 7) (Gunter’s Space Page)

- ThrustMe puts into orbit the first satellite using iodine to propel itself (Technology Watch)

The first Chinese launch was November 3, 2019 at 3:22 AM (UTC) when a Long March 4B rocket took the last Gaofen mission to space. There were also three test bed co-passengers: Huangpu 1, Sudan Scientific Experimental Satellite 1 and Xiaoxiang-1 08.

(Huangpu 1, a technology demonstration satellite developed by the Shanghai Institute of Satellite Engineering for a planned constellation of low Earth orbit satellites, was also launched. Beyond this vague description, we know little about it.)

Sudan Scientific Experimental Satellite is — you guessed it — an experimental satellite from Sudan. It is the very first satellite for the country.

SRSS-1 is also a Chinese-made Earth observation satellite, developed in partnership with the Sudanese government in an effort to modernize the country’s struggling economy. The Institute of Space Research and Aerospace (ISRA) was created back in 2013 & this launch was a part of that program. That it continues despite the military-backed ouster of the leader responsible back in 2018 speaks for the benefit the program is perceived to be capable of bringing to the African nation.

Other goals include the launch of a Sudan-owned communications satellite, and the development of various space-based industry. They were partners in last April’s launch of Arabsat-6A by SpaceX aboard a Falcon Heavy rocket, with Sudatel (state-owned communications company) owning four Ka-band transponders aboard that satellite.

The largest payload on board & the primary mission of the launch, was the GaoFen 7 Earth observation satellite. Chinese officials have publicly proclaimed the launch a success, and US military tracking indicates the satellite is now in a near-circular orbit approximately 310 mi / 500 km up. With an orbital inclination of 97.5 degrees to the equator, just enough retrograde to counteract the tug of Earth’s gravity due it its rotation, we can call this what it is: a good sun synchronous orbit (SSO).

The GaoFen 7 is the latest in a constellation of “civilian-accessible” high resolution (sub-1 m) Earth-imaging satellites which is part of the CHEOS system (China High-Resolution Earth Observation System). Developed by the China Academy of Space Technology (a state-owned civilian contractor) the GaoFen have been launching in support of CHEOS since 2013, and Chinese officials have previously released several images taken by these satellites. They have also released the specifications of a number of previous GaoFen satellites prior to launch, however this was not done for GaoFen-7.

According to Xinhua news agency, the primary customer for GaoFen & CHEOS imagery are the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and the National Bureau of Statistics.

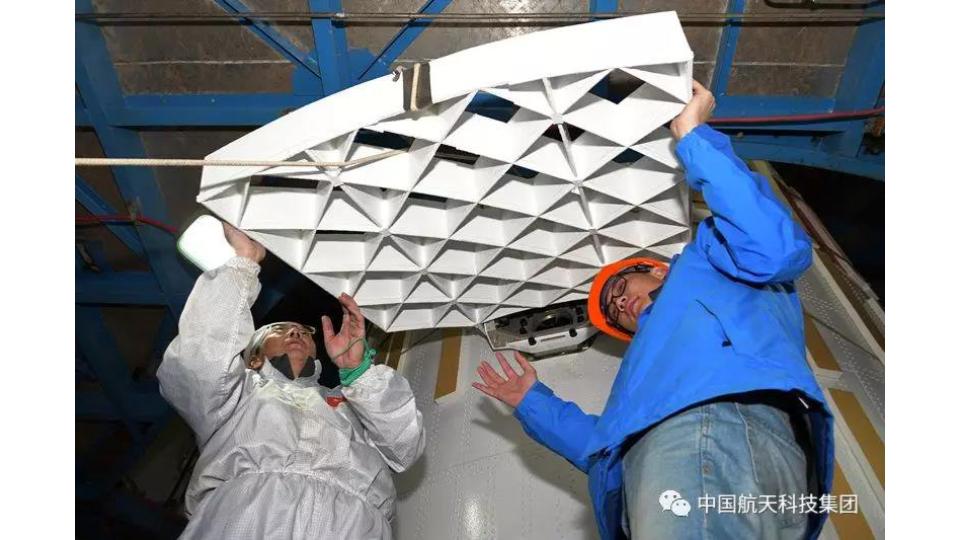

Credit: ThrustMe

Also called “Dianfeng,” Xiaoxiang-1 08 is a 6U CubeSat built by Spacety Co. Ltd., a privately-owned Chinese smallsat manufacturer. However in an unusual East-West partnership, the Chinese sat maker paired up with French company ThrustMe to have the latter provide a 1st-of-its-kind propulsion system called the I2T5, which uses cold gas non-pressurized solid iodine for fuel. In this case, a solid block of iodine is heated via electric elements, and in the unpressurized vacuum some of that sublimates into a pressurized vapor, which is then used as thrust.

“The technical difficulty lies in controlling the rate of iodine ejected in gaseous form to get the proper thrust,” says Gautier Brunet, Director of Operations at ThrustMe, as he discussed the technical hurdles involved in producing the new design. However, there is significant motivation to do so: “Xenon is almost 100 times more expensive than iodine,” says Brunet, referring to a rare noble gas often used in other electrical or ion thruster, an industry ThrustMe is also part of. In addition, Iodine is not flammable & does not require an oxidizer for this type of thruster.

This test model is expected to allow Xiaoxiang-1 attitude & orientation control, but is not yet strong enough to allow orbital changes. That may come later, as the company has plans to upscale this design if successful, and is also working on an iodine-fueled ion drive. The company hopes these will extend the lives of future microsats, make them more versatile & survivable during their lives, and eventually allow for planned controlled deorbits as well.

ThrustMe said in a statement: “From idea to launch in less than a year, from contract to launch in eight months, ThrustMe and SpaceTy, with this first launch together, demonstrate the importance of open-minded international collaborations.”

The company is also working with NASA on the Lunar IceCube project, which is projected to send a CubeSat to lunar orbit in 2021.

First Long March 4B with grid fins!! LaunchStuff on Twitter reports that “[t]he goal of the gridfins on the old vehicle is to shrink the SMASHDOWN!!! zone for safety and give valuable data to scientists working on the new generation of reusable vehicles.”

- Boeing tests crew capsule escape system (Spaceflight Now)

- Boeing performs Starliner pad abort test (Space News)

- Boeing/Starliner in successful Pad Abort Test; some issues observed (NASASpaceflight.com)

- Pad Abort Test of Boeing’s Starliner Spacecraft, Nov. 4, 2019 (YouTube)

Also on the morning of 04NOV2019 The CST-100 Starliner performed a pad abort test out at the White Sands test range. This was done as part of the testing program the NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, which is intended to produce the next generation of American-made space launch vehicles capable of sending humans to Earth orbit & beyond… something NASAA has been unable to do since the retirement of the Space Shuttle fleet.

At 09:15, some 15 minutes into a planned test window, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner was sent the command to execute its launch abort sequence, triggering a “short, but eventful” 78 second flight through the clear morning sky to a controlled landing on the floor of the New Mexico desert.

CREDIT: NASA TV

The test was designed to simulate a situation in which the vehicle needs to quickly escape from a potentially hazardous situation while still on the ground. The 4 Launch Abort Engines (LAEs) and 12 Orbital Maneuvering Engines (OMEs) were simultaneously triggered, producing about 800,000 Newtons / almost 180,000 pounds of thrust. Astronauts & equipment inside the capsule would have experienced roughly 5 Gs for 5.1 seconds on their way to a top speed of 650 mph / 1050 kmh & a maximum altitude of 1350 m / 4430 ft.

At this time, less than 20 sec into flight, the thruster pulsed once again, causing the craft to flip into a tail-first attitude, allowing the 3 drogue chutes to deploy (they did), which in turn allows for the mains to follow, keeping the craft stable for the separation of the Service Module (SM) to drop free at about T+35 sec. During the test, though, it quickly became clear that only 2 of the 3 main chutes had deployed. These were sufficient to guide the craft to a soft landing atop airbags which inflated according to plan around the bottom of the vehicle, and NASA & Boeing were quick to announce that this would have been an “acceptable” result in an actual emergency.

According to a NASA statement on the chutes, “Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft completed a critical safety milestone on Monday in an end-to-end test of its abort system. Although designed with three parachutes, two opening successfully is acceptable for the test perimeters and crew safety. After one minute, the heat shield was released and airbags inflated, and the Starliner eased to the ground beneath its parachutes.”

Boeing also released a statement: “Today’s pad abort test was a milestone achievement for our CST-100 Starliner team, for NASA, and for American human spaceflight. We will review the data to determine how all of the systems performed, including the parachute deployment sequence. We did have a deployment anomaly, not a parachute failure. It’s too early to determine why all three main parachutes did not deploy, however, having two of three deploy successfully is acceptable for the test parameters and crew safety. At this time we don’t expect any impact to our scheduled Dec. 17 Orbital Flight Test. Going forward we will do everything needed to ensure safe orbital flights with crew.”

Also concerning to some observers was the large plume of reddish-orange smoke which was seen pouring from the SM after it crashed. All 18 thrusters on the Starliner are powered by a UDMH/DNTO mixture, and there was speculation that this might complicate an actual recovery operation. However, some experts noted that during actual launch operations, the SM is likely to end up in the ocean while the Starliner steers back toward land. An ocean impact is expected to largely negate the type of fire seen when it crashed into the ground on Monday, largely due to the two components mixing readily w/water, dispersing & decomposing without producing the large, hazardous plume of smoke.

An uncrewed Starliner will fly to the ISS later this year in a December test flight aboard a ULA Atlas V rocket. This craft will not have the same type of parachutes installed w/the abort system, as it will be uncrewed, and any change in the loading will require extra time that an already-delayed NASA would only spend grudgingly. Also, it’s not as critical to save all of the equipment.

Parachute issues have plagued both Boeing & SpaceX during development, though both companies seem to be incorporating the data from those failures rapidly, particularly in SpaceX’s case. That company plans to have its 1st crewed flight to the ISS sometime in January 2020, while Boeing’s 1st crewed flight is tentatively scheduled for sometime in the 1st quarter of 2020.

- BD-3 I (Type 2) (Gunter’s Space Page)

- Geosynchronous orbit types (Wikipedia)

- Beidou-3 I3Q (IGSO-3) (RocketLaunch.Live)

- BeiDou (Wikipedia)

- List of BeiDou satellites (Wikipedia)

The second Chinese launch happened on Monday, November 4th at 5:43 PM (UTC), when the BeiDou-3 I3Q mission took off on board a Long March 3B rocket.

This particular BeiDou satellite is destined for an inclined geosynchronous orbit. What this means is that instead of the satellite appearing to stay in one spot from the ground, it will appear to trace out a figure-8 — also known as an analemma — in the sky. There are already 11 other BeiDou satellites in orbit, but only two in this particular inclined geosynchronous orbital slot having 55° inclination.

What’s the benefit of this type of orbit?

The highly inclined orbit means that at northernmost, the satellite appears to be near directly over head from most places in China (furthest north latitude is ~55 deg. N) for several hours. If you have, say, three of these in the same orbit, then at various times of day each one will take over that spot near the zenith. This position information can then be programed into the satellite’s signals, informing user terminals that this particular signal is from this particular satellite which observes itself in a particular orbital position.

WIki says there will be three in the inclined orbit, plus one back-up. This makes it sound very much like the Japanese QZSS system (Quasi-Zenith Satellite System).

You will thus have 3 sets of BeiDou (“Northern Dipper”) signals:

- 1 set from GEO, which will provide unmoving guideposts;

- 1 set from MEO which will provide the set we’re all used to from GPS, GLONASS, etc., and finally

- 1 from these “quasi-zenith” guideposts.

The combination, in theory, should provide ridiculously good navigational data for air, sea & land based receivers. The type of combination network can also be seen in the European EGNOS / Galileo system, which can provide data w/accuracy & refresh rate consistent with, e.g., landing & final approach for aircraft in flight.

That rounds out our show for today.

Thank you all for listening. The Daily Space is produced by Susie Murph, and is a product of the Planetary Science Institute, a 501(c)3 non profit dedicated to exploring our Solar System and beyond. We are made possible through the generous contributions of people like you. If you would like to learn more, please check us out on patreon.com/cosmoquestx During the month of November we are running a special fundraiser to support our server costs for 2020. We project costs of $1450 for all of our websites. If you would like to help us reserve our place on the internet, you can donate at streamlabs.com/cosmoquestx. Your donations are tax deductible where allowable in the world.

Each live episode of the Daily Space is archived on YouTube. If you miss an episode here on Twitch.tv, you can find it later on youtube.com/c/cosmoquest. These episodes are edited and produced by Susie Murph.

We are here thanks to the generous contributions of people like you who allow us to pay our staff a living wage. Every bit, every sub, and every dollar committed on Patreon.com/cosmoquestx really helps. If you can’t give financially, we really do understand, and there are other ways you can help our programs. Right now, the best way you can help is to get the word out. Let you friends know, share our channel to your social media, or leave a recommendation. You never know what doors you are opening.

We really wouldn’t be here without you – thank you for all that you do.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.

We record most shows live, on Twitch. Follow us today to get alerts when we go live.